On 21 November 2013, the Ukrainian president V. Yanykovych decided to suspend the negotiations on the Association Agreement with the European Union (EU). Going along with a closer relation to Russia, this decision provoked demonstrations, peaceful at first, known as EuroMaidan or Maidan. Quickly, demonstrations and their repressions toughened, to the point of being deadly. In Eastern Ukraine and in Crimea was found evidence of Russian implication in separatist movements. Crimea itself was officially annexed by Russia on 18 March 2014. These events made the Europeans face a new security challenge in their immediate neighborhood, while they thought peace, security and stability of national borders were now well established.

After more than six months of growing violence and political instability, in June 2014, the new Ukrainian president P. Poroshenko (who succeeded to V. Yanukovych after the latter had fled to Russia) was invited by the French president F. Hollande to the commemoration ceremony of the 1944 Normandy landing. This invitation is seen as the first attempt at getting the warring parties Ukraine and Russia together, in order to discuss the issues linked to the Ukrainian conflict. This initiative led, on 12 February 2015, to the second Minsk Agreement, that Ukraine, Russia, Germany and France—a diplomatic quartet known as the “Normandy format”—came up with after (harsh) negotiations. This “Minsk 2” diplomatic roadmap followed the first (and failed) Minsk Agreement, concluded between Ukraine, Russia, the separatists and the OSCE in September 2014. Although more respected by the different parties, including belligerents on the front lines, the implementation of Minsk 2 is not yet complete to this date. Nonetheless, whatever the final outcomes of this second set of commitments, France and Germany played a key role in creating contacts between Ukraine and Russia, and helping coming up with getting-out-of-the-crisis plans.

Why, how, and with what outcomes did France get involved in the Ukrainian conflict? What types of issues are at stake when considering French involvement in these events?

As we will see, the “Normandy format” can be considered as the main accomplishment for French diplomacy, as it at least led to negotiations between the warring parties. Overall, France, along with Germany, was part of a European consensus, that both allowed concrete actions on the EU level and confirmed the possibility for the French and the German to lead the negotiations with Ukraine and Russia. French involvement can also be read as the will to play the role of a diplomatic power in Europe, by showing both its power of initiative and its power of influence over the course of events.

As always in international relations though, France has encountered conflicting interests since the beginning of the Ukrainian conflict and has gone through some trouble in dealing with them. One of the main French priorities appeared to be the maintaining of a dialogue with Russia. Security and economic issues were also at stake, the Mistral case being particularly relevant in the matter.

Getting down to work: how the French initiated the “Normandy format”

Launching a new diplomatic initiative

The “Normandy format” was given birth during (and called after) the 1944 Normandy landing commemoration ceremony, in June 2014, in France. Asking the newly elected Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko to join the celebration was a decision made by French president F. Hollande. One must add that the latter had been under pressure from the Ukrainian community for several weeks, as the violences went on in the Eastern part of Ukraine. The official ground for this invitation was the participation of many Ukrainians in the Soviet army’s fight against Germany during World War II: Ukraine was, therefore, as legitimate as Russia for being part of the commemorations. More than just recognizing the historical importance of Ukraine as part of the Soviet army, this diplomatic initiative meant officially legitimizing Poroshenko as Ukraine’s president[1]. This invitation was also a way to try and have a beginning of informal dialogue between the two warring countries leaders, as V. Putin was also to be present at the ceremony.

The participation of the Ukrainian president to the June 2014 event launched a series of meetings between V. Putin, P. Poroshenko, A. Merkel and F. Hollande, with the goal of finding a peace agreement for Ukraine. Paradoxically, this format underlines the absence of the EU as an effective diplomatic party in the discussions, although it can be argued that the EU is one of the reasons the conflict happened in the first place. Germany and France were, more or less implicitly and by default of other efficient means, chosen as representatives for the whole EU[2], which both undermined the EU diplomacy agents and led (probably) to a format that Russia was more inclined to deal with. Leading the EU as a united bloc in its attitude towards Russia meant for the duo to put at risk their own relation with Russia[3]. Although France had less to lose from economic sanctions than other EU countries (including Germany), it did take a strong stand when it called the Mistral warships sale into question. Although this decision came up pretty late in the unfolding of events…

The Minsk Agreement: a success-to-be?

In September 2014, several attempts to conclude a cease-fire, led by the “contact group” (Russia, Ukraine, separatists, OSCE), took place in Ukraine. The first Minsk Agreements were declared agreed upon on 5 September 2014, but quickly disintegrated as the cease-fire did not hold. In February 2015, the Minsk process was relaunched, this time with the support of the French president and German chancellor. Although this second attempt has officially lasted until now, it is far from implemented. First of all, the new cease-fire did not hold very long. Fightings resumed pretty quickly in 2015. Besides, continued Russian intrusion, as well as internal blockages, prevented Ukraine from implementing the reforms promised to both Ukrainians and external governments. While supportive of Ukraine, France and Germany essentially pushed for only one aspect of the Minsk Agreement, the decentralization reform (which is very differently understood from a Ukrainian, a European or a Russian perspective), accommodating their Russian partner concerning the withdrawal of heavy weapons and foreign troops from Ukrainian territory. Besides not being as urgent as a cease-fire, the request for a “special status” in the Donbas region would pose a serious threat for Ukraine. Such a status would be provided to a region in which separatists took over by means of arms, while being obviously supported by a foreign state, ie Russia. No democratic representation, nor respect for Ukraine’s sovereignty would have been respected in giving a “special status” to the Donbas.

To this date, one of the last French diplomatic gesture towards Ukraine was the visit to Kiev of the newly appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs, Jean-Marc Ayrault, along with his German counterpart Frank-Walter Steinmeier, on February 22nd

and 23rd 2016. In their joint declaration, the two Ministers criticized Russia as the violator of Ukraine’s sovereignty. This appears to be a progress, from a Ukrainian point of view, as the ambiguous formulation on Ukraine’s territorial integrity in Minsk 2 did not clear the issue of Crimea[4]. Despite this more direct accusation of Russia, the two Ministers highlighted that the Minsk Agreement was the only path towards conflict resolution. They particularly underlined the absolute necessity for reforms, especially against corruption and for decentralization. As they put it, “decentralization of the State and of the administration can help governmental action to be closer to citizens, more efficient and more transparent”.

Read also: 12 months of Minsk-2. Examining a year of violations

Yet, pressure for the implementation of Minsk 2 seems to have been turning from Moscow unto Kiev in the past few weeks. On 11 February 2016, Le Monde quoted a French diplomat feeling that “the ‘fatigue’ on the Ukrainian conflict might quickly become a ‘fatigue’ on the Ukrainian partner, judged as non-reliable. […] The issue of sanctions against Russia […] would be tackled with in a very different way, despite Moscow not giving up its ulterior motives and maneuvers”[5]. Kiev is beginning to be the one under Western pressure to implement the reforms agreed upon in Minsk 2, including the decentralization part, which creates much political turmoil inside Ukraine. Recently, French attitude has indeed officially turned from supporting to accusing Kiev. During his visit to Moscow, on 19 April, Jean-Marc Ayrault accused Ukraine of being the one blocking Minsk 2 success[6], saying that Kiev “must implement reforms and introduce, in particular, amendments to the constitution on the special status of the Donbas and the electoral process in the region”.[7]

Leading the EU

The coming back of the Franco-German couple?

The joint initiative of Paris and Berlin in leading the Minsk negotiations and establishing contacts between the warring parties has left out the EU as a potential diplomatic power. Other EU member states have rallied behind France and Germany, leaving them the duty of dealing with Russia and Ukraine on behalf of the EU. This joint diplomatic move was seen by many as the revival of the famous “Franco-German couple”. The sacrifices both had to make—for instance, loosening economic ties for Germany, the Mistral issue for France—pulled the two of them closer to each other, reinforcing overall European unity. Although EU member states did not have the same opinions towards sanctions at first, researcher E. Jahn explains that “the different stances taken by the individual western governments towards the Russian aggression against Ukraine to date have been overarched by a common policy of negotiation and sanctions”[8].

Choosing words and sanctions over weapons?

NATO was clear: no direct military intervention will take place in Ukraine. But the question of arming Ukraine is another, although linked, issue. The United States tend to be in favor of this possibility, but appear, for now at least, to let the Europeans tackle the problem and have confined their help to some military advising. The Georgian conflict, in 2008, had created a precedent in the attitude of some EU countries, including France, towards the potential integration of what Russia considers as its “near abroad”: France and Germany categorically refused the integration of Georgia and Ukraine in NATO (willing not to be bound by article 5). In a joint press conference, on 22 April 2015, F. Hollande and P. Poroshenko both reaffirmed that France would not deliver lethal weapons to Ukraine[9]. At the European level, there is a general consensus on not delivering any weapon to Ukraine. This attitude is justified by the will to not aggravate the situation, but can also be read through the prism of European demilitarization since the end of the Cold War.

Conflicting interests

France: rather South than East

Traditionally, France is rather turned towards its Southern neighborhood than the East of the EU. For instance, France did not sign the Budapest Memorandum that supposedly guaranteed Ukraine’s territorial integrity since 1994, after giving up on its Soviet nuclear weapons. Instead France signed “security guarantees”, a shallower commitment. In the French 2013 White Paper for National Defense and Security (Livre Blanc Défense et Sécurité Nationale, 2013) is reminded the necessity to keep cooperating with Russia, to take into consideration its preoccupations. For instance, France, along with Germany, categorically refused Georgia’s adhesion to NATO, while the US left the door open.

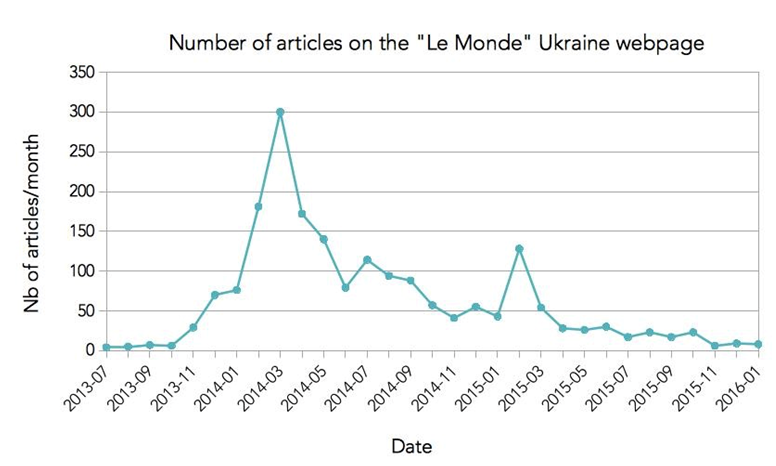

During the unfolding of the Ukrainian conflict, French positions reflected this absence of interest in the buffer zones between the EU and Russia, of which Ukraine is part. For instance, it is noticeable that almost no article was dedicated to Ukraine before the Maidan in the widely distributed French newspaper Le Monde (see Figure below).

As mentioned, France is traditionally rather turned towards the Southern neighborhood of Europe, with which the country has historical and economic relations. Yet, events happening on the Eastern side of the EU have been used as means of promotion for France in the context of international relations. During the Georgian war, France was presiding the EU. Former French president N. Sarkozy used this position to handle the situation and strike a deal with Russia. Although promoted as an example of French diplomacy efficiency, the outcomes of the Georgian conflict were rather in favor of Russia, which won a political recognition of the military situation, as well as the categorical refusal by France and Germany for Georgia and Ukraine to join NATO. Identically, even though EU member states found a consensus and agreed on sanctions against Russia, many academics thought the reactions were pretty light.

Interests versus values: France in need of Russia

While France surely got involved in Ukraine with a lot of good intentions, wanting to defend democracy and territorial integrity, it was as surely caught up by the obstacles its own interests raised during the conflict.

France has a pretty long history of alliances with Russia. Under the presidency of N. Sarkozy, French diplomacy had been working at developing the political, economic, and even military relations with Russia. A dynamic that went on when the Elysée hosted a new president, F. Hollande, from 2012 on. This renewed relation was epitomized by the sale contract of French warships, the Mistral, to Russia, in 2008. Up until May 2014, French authorities were very clear that the sale of Mistral warships to Russia would not be cancelled, despite the events in Ukraine and the protests of their NATO allies, who had been expressing concerns since the beginning of the negotiations, several years ago. Yet, in September 2014, F. Hollande announced the suspension of the sale, at the relief of P. Poroshenko, who thanked him later, at a joint press conference, for his clear statement[10]. A year later, in September 2015, the French National Assembly approved the cancellation of the sale of the Mistral warships, which had been negotiated directly with Russia beforehand. Still, throughout the conflict opposing Ukraine and Russia, Paris has been willing to keep the dialogue open with Moscow. On 7 March 2014, president F. Hollande reminded the French support to Ukraine but also that “our objective is also to always keep open the path to dialogue, so that Russia — I am speaking here of president Putin — has the possibility, if it decides to do so, to grab the lifeline thrown to it”[11]. Still, more recent academic works underline the security challenge that Russia has become for West European countries. M. Mendras, a French researcher in political science, wrote in 2016 that “the EU cannot dismiss the security urgency, and must address it, in connection with NATO and the United States. We need to be prepared for a long standoff with Moscow”[12].

Conclusion

The diplomatic intervention of France and Germany has led to the steadier format of negotiations since the beginning of the conflict in Ukraine: the Normandy format. Although the Minsk Agreement 2 still holds—after more than a year of having been signed—it remains fragile, especially because of the lack of consensus on its implementation, both at the international and national level. For instance, decentralization has different meanings whether the perspective is Russian or Ukrainian, and the Ukrainian government has trouble legislating on the matter because of internal political turmoil.

Yet, the Franco-German intervention also epitomizes the exceptionally, if not surprisingly, united European reaction to the conflict. For example, sanctions were adopted as a consensus and gained much strength by being a European decision, rather than a national one. Each European country had its possible conflicting interests, among which France was not the least, as was revealed by the Mistral warships case. Currently, the situation seems at a turning point.

The Normandy format is still relevant for negotiations between the warring parties. But the slow implementation of the Minsk Agreement has forced Berlin, Kiev, Moscow, and Paris to postpone the deadline from the end of 2015 to an undetermined date. This indetermination might reveal itself rather dangerous, as the lifting of European sanctions is conditioned to the implementation of Minsk 2. But how long will European unity stick to the initial decision?

[hr]

- [1]. SANIAL Amandine, 06.05.2014, “Pourquoi l'Ukraine a finalement été invitée aux commémorations du Débarquement”, Le Monde.

- [2]. DUTA Paul, 2015, « The OSCE strategies of mediation and negotiation carried out in Moldova and Ukraine », Research and Science Today, n°2, p.82-91.

- [3]. SCHMIDT-FELZMANN Anke, 2014, « Is the EU’s failed relationship with Russia the member states’ fault? », L'Europe en Formation, n° 374, p. 40-60.

- [4]. ibid.

- [5]. VITKINE Benoît, 02.11.2016, “Un an après les accords de Minsk, Paris et Berlin s'inquiètent des ambiguïtés de Kiev”, Le Monde.

- [6]. AVRIL Pierre, 04.19.2016, “Ayrault sermonne Kiev et épargne Moscou”, Le Figaro

- [7]. 04.21.2016, “Nous accusons”, KyivPost https://www.kyivpost.com/article/opinion/editorial/nous-accusons-412480.html

- [8]. JAHN Egbert, May 2015, « Chap. 16 - The Exacerbation of the Competition Between Brussels and Moscow Over the Integration of Ukraine », World Political Challenges, Springer, Verlag, Berlin, p.285-311.

- [9]. Joint press conference, F. Hollande and P. Poroshenko, Elysée (Paris, France), April 22nd 2015.

- [10]. Joint press conference, F. Hollande and P. Poroshenko, Elysée (Paris, France), April 22nd 2015.

- [11]. March 7th 2014, declaration of president F. Hollande, Paris. Original quote in French: “Mais notre objectif, c’est aussi de laisser toujours ouverte la voix du dialogue, de manière à ce que la Russie - je parle ici du Président POUTINE - puisse saisir, autant qu’elle sera décidée à le faire, la perche qui est tendue.”

- [12]. MENDRAS Marie, 2016, « The West and Russia: From Acute Conflict to Long-Term Crisis Management », DGAP and Center for Transatlantic Relations, 5p.