From ‘Euromaidan’ to ‘Maidan’

Contents

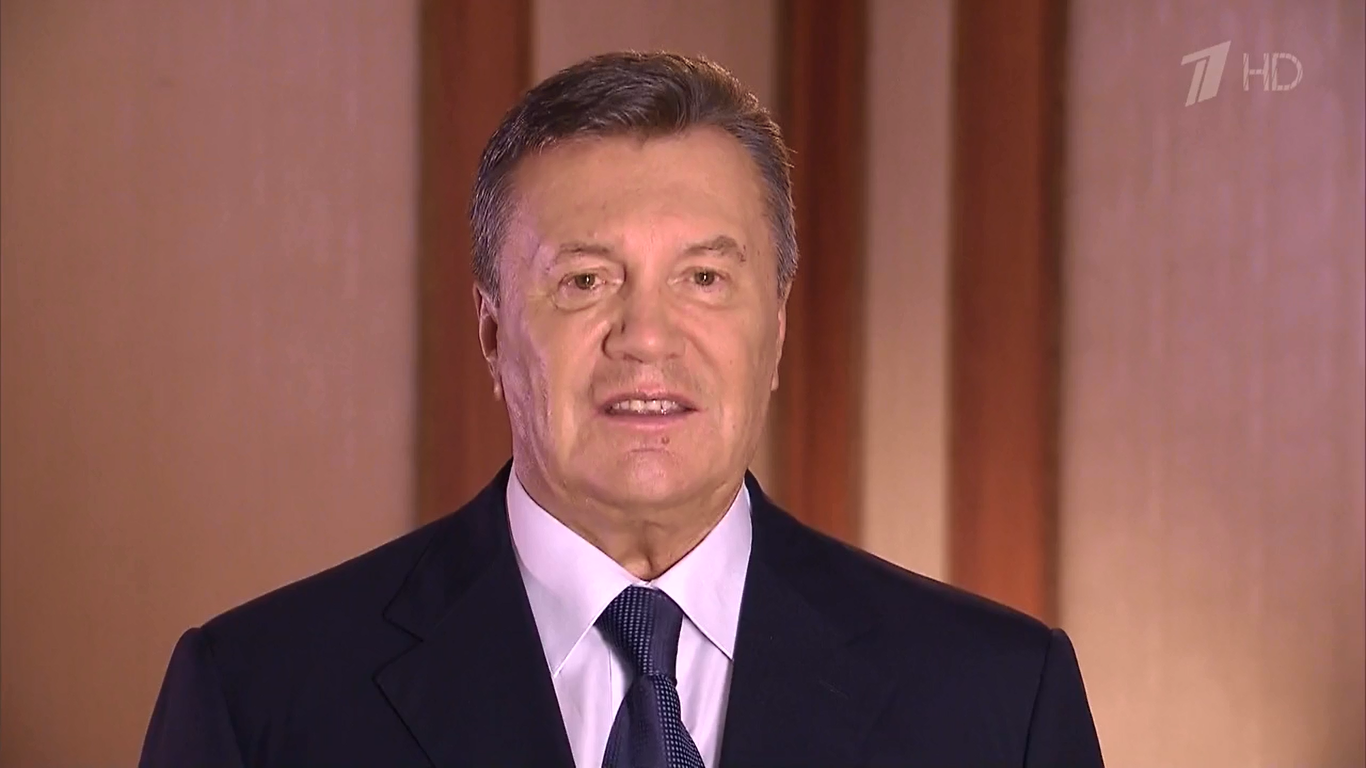

The Maidan movement began spontaneously on November 21, 2013, and was soon being branded as ‘Euromaidan’ due to the pro-EU integration dynamic of the initial protests. Kyiv’s academic youth led the early protests against President Yanukovych’s reversal of the country’s European integration course. They also protested against the prospect of Ukraine’s integration into President Putin’s rival Eurasian project.

In the course of the following weeks, what had begun as a pro-European movement (slogan: ‘Ukraine is Europe!’ – Ukr.: ‘Ukraina – tse Yevropa!’) gradually morphed into a much broader popular uprising against the kleptocratic regime of President Yanukovych and against the ‘occupation’ of the whole country by the Donetsk elite. It was also an uprising against the political ‘Eurasianization’ of Ukraine, following the model of the Russian Federation and the former Soviet republics of Central Asia. As the protests grew, the number of European Union flags on display decreased, while the number of blue-and-yellow national flags of Ukraine increased.[20] More and more frequently the ‘People of Maidan’ (Ukr.: narod Maidanu) chanted the slogan: ‘Glory to Ukraine!’ (Ukr.: ‘Slava Ukraini!’). Again and again, the Ukrainian national anthem was intoned on Maidan. It became fashionable to wear Ukraine’s traditional embroidered shirts (Ukr.: vyshyvanka, Pl. vyshyvanky) and to speak Ukrainian in public. The Maidan movement nationalized itself and consolidated the hitherto insecure identity of many Ukrainians.

On January 19, 2014, after weeks of peaceful protests, sections of demonstrators turned to violent confrontation with the riot police forces guarding the government district in downtown Kyiv. Members of the nationalist Right Sektor group would later boast of initiating the clashes.[21] This outbreak of violence came in response to the adoption of draconian anti-protest legislation on 16 January, 2014, by the parliamentary majority of the ruling Party of Regions and the Communist faction. These ‘emergency laws’, were soon dubbed the ‘dictatorship laws’ (Ukr.: Zakony o dyktature) by the opposition. They were signed into law by President Yanukovych the following day. Attempts by riot police to enforce the new legislation and forcibly clear the tent city on Maidan met with resistance from volunteer units of the Madains ‘Self-Defence’ (Ukr.: Samooborona Maidanu). These self-styled ‘Defenders of Maidan’ (Ukr.: oborontsi Maidanu) were divided into ‘Hundreds’ (Ukr.: sotnya, Pl. sotni; their leaders being named ‘sotnyky’) in reference to traditional Cossack cavalry formations.

Without this violent confrontation, the Maidan movement may not have achieved its victory. If the Maidan movement had failed, Russia would probably not have annexed Crimea and would not have ignited war in the Donbas. While, in Mahatma Gandhi terms,[22] a ‘victory attained by violence’ is an ambivalent one, President Yanukovych would, following the alternative scenario, in all probability have led Ukraine into Putin’s Eurasian Union[23] of post-Soviet dictatorships, and thereby de facto subjected his country again to Moscow’s rule – a gloomy prospect for Ukraine’s youth.

The victory of the Maidan movement led to ‘revolutionary-parliamentary’ regime change in Kyiv. Arguably, the revolutionary violence was, given the circumstances, justified – as was the Storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, in Paris. President Yanukovych’s regime was criminal. He himself and his clan (‘The Family’) enriched themselves to an unprecedented degree at the expense of the Ukrainian State, effectively robbing the Ukrainian people. The idea of waiting to vote him out of office in the regular presidential elections scheduled for 2015 was hopeless: Yanukovych had already consolidated most state prerogatives and enormous resources in his hands. Using “political technology,” he may have secured a second term for himself.

In the immediate aftermath of the Maidan massacre of 20 February, and with the aim of avoiding further bloodshed, the foreign ministers of Germany, France and Poland, Franz-Walter Steinmeier, Laurent Fabius and Radoslaw Sikorski, negotiated an agreement between President Yanukovych and the leaders of the three parliamentary opposition factions: Arseniy Yatsenyuk (Fatherland Party, Ukr.: Bat’kivshchyna), Vitalii Klitschko (UDAR Party) and Oleh Tyahnybok (Freedom Party, Ukr.: Svoboda). Russia’s Human Rights Commissioner, Vladimir Lukin, participated in the negotiations, but refused to co-sign the agreement.

This agreement was a waste of paper from the outset, because the leaders of the parliamentary opposition had no control over the revolutionary processes at play within the Maidan movement. The Maidan movement rightly rejected this agreement, because it stipulated “early” presidential elections in December 2014 – only two months before the regular election date (January / February 2015). Yanukovych would have ensured his ‘victory’ in these elections by employing all of the administrative, financial and judicial means at his disposal – and he would have taken revenge afterwards.

The revolutionary Maidan movement was democratically legitimized through subsequent Ukrainian elections – if any subsequent correction were needed. The presidential elections in May 2014 were won by the ‘Maidan Candidate’ Petro Poroshenko, with an unprecedented first round landslide majority of 55%. In the parliamentary elections in October 2014, pro-Ukrainian and patriotic parties gained an almost two-thirds-majority.

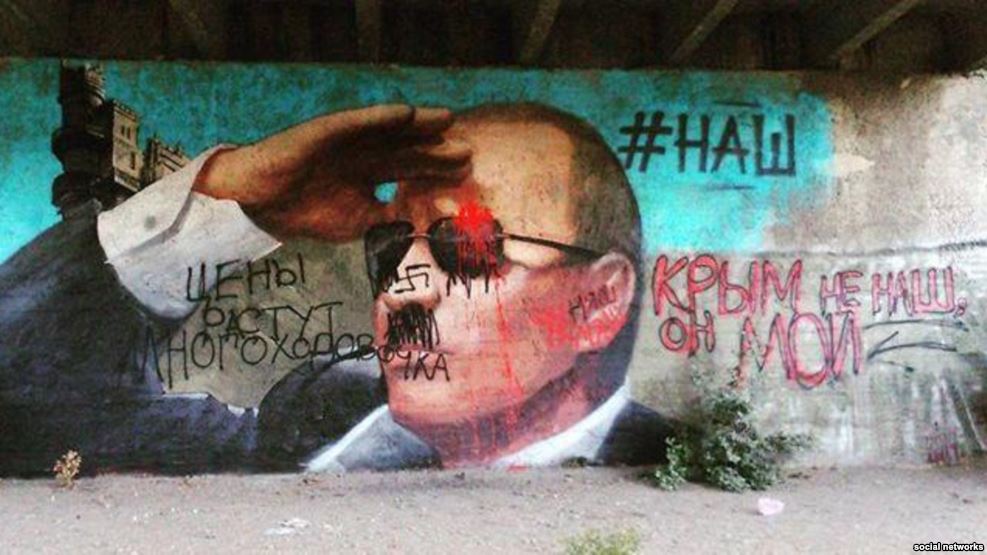

As a result of the annexation of Crimea and military intervention in the Donbas, Russian President Putin effectively excluded almost 4 million traditionally pro-Russian voters from taking part in these 2014 Ukrainian national elections. These pro-Russian constituencies had previously served as the bedrock of electoral support for Viktor Yanukovych’s Party of Regions. Altogether 27 electoral districts, 12 on the Crimean peninsula (1,8 million elegible voters), 9 out of 21 in the Oblast Donetsk, 6 out of 11 in the Oblast Luhans’k (1,9 million voters in both Oblasts) did not take part in the elections. In this sense, the ‘temporary loss’ of Crimea and one-third of the Donbas has actually made Ukraine more ‘Ukrainian’. Today the country is more patriotic and more pro-European than ever before.

From ‘Anti-Maidan’ to war of secession in the Donbas

The ‘People of Maidan’ (Ukr.: narod Maidanu) did not represent the entire population of Ukraine. Large sections of the population in eastern and southern Ukraine did not share in the national sentiment which was awakened by the Maidan movement. President Yanukovych’s Party of Regions rallied these forces in defense of their leader (slogan: ‘Yanukovych is our President!’, Ukr.: ‘Yanukovych – nash president!’). In the major cities of east and south Ukraine, a so-called Anti-Maidan movements soon emerged. Paid „anti-demonstrators“ were, for instance, taken by bus and rail from Eastern and Southern cities to Kyiv. In a park next to the building of the Verkhovna Rada (Parliament) a stage was set up for them, where the Party of Regions temporarily staged an “Anti-Maidan”.

These activists initially imitated the tactics of the Kyiv Maidan movement. However, wooden bats were soon replaced by firearms looted from the arsenals of the local (often openly sympathizing) security services. After the annexation of Crimea by Russia, some separatist-minded Russian speakers thought the time had come to attempt to seize the Donbas by force of arms. The secession movement of ‘New Russia’ (Russ.; Novorossiia)[24] was supposed to encompass the whole of South East Ukraine (Russ.: Yugo-Vostok).

Read also: Meet the people behind Novorossiya’s grassroots defeat

The existence of resentment towards Kyiv among many ethnic Russians and Russian-speaking ethnic Ukrainians in eastern and southern Ukraine should not be taken to imply that a majority of this discontented segment of society wished to join Russia, or follow the example of the Anschluss of Crimea. According to polls taken before the war, only one-third of Donbas residents held genuinely separatist sentiments. This explains why Putin’s secessionist Novorossiia project struggled in the wake of the awakening of Ukrainian national sentiment among the majority of the people living in the territory earmarked to become “New Russia.” With the exception of the Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts, the other six eastern and southern oblasts of Ukraine which had been identified by Moscow as part of Novorossiia did not rally to join Putin’s separatist adventure. Even in the Donbas itself, the separatists have initially managed to exert military control over merely one-third of the macro-region. This modest success has only proved possible because losses of combatants and weapons are offset by continuous replenishment from Russia. The Russian President miscalculated over the Ukrainian reaction to his military intervention: ‘New Russia’ did not fall into his lap as Crimea had done. Putin did not foresee that by supporting separatism in Ukraine, he would arouse militant Ukrainian patriotism.