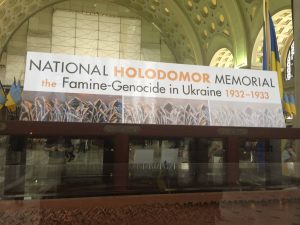

On Saturday November 7, 2015, a long-awaited memorial to a little-known modern genocide will be dedicated in Washington D.C. It will be accompanied by an exhibit at Union Station aimed at raising awareness among Americans of what Ukrainians call the Holodomor, literally “death by hunger,” an engineered famine which took the lives of anywhere from 4 to 10 million Ukrainians in 1932-33 during the Soviet regime of Josef Stalin.

Congress allocated the small plot of land for construction of a memorial with Kyiv authorities in 2006, under then President Viktor Yushchenko, the infamously poisoned politician brought to power during Ukraine’s popular Orange Revolution. The memorial was ultimately funded with private donations. Ukrainian-American architect Larysa Kurylas designed the Holodomor “Field of Wheat” monument, a stark bronze sculpture of wheat stalks receding into the distance, symbolizing the rich agricultural lands and traditions of Ukraine so cruelly turned against the population to starve them into submission.

Until recently, most Americans probably couldn’t identify anything significant about Ukraine’s history or even find it on a map. Many are still surprised to learn, for example, that Ukraine with a population of over 46 million is one of the most populated and the largest country by geographic area in Europe. The very fact that Ukraine is wholly inside Europe even comes as a surprise for many Americans. The reason for this lack of knowledge is the result of Ukraine’s centuries-old interconnectedness with its imperial Russian neighbor, under the Russian Empire of the Tsars and then under the totalitarian communists of the Soviet Union. As a result, most of what we have managed to learn about Ukraine has been written through the lens of Russian and Soviet historiography. Importantly, for most of this history, Ukraine has been a colony of more powerful states. During the 20th Century, its colonization by both Stalin’s Soviet Union and Hitler’s Nazi Germany led to Ukraine being ground zero for arguably the two most horrific events of that century, the Holodomor in the 1930s and the Holocaust of the 1940s.

Much has been written and rightly continues to be written about the Holocaust. New facts and more accounts seem to come to light every day, unearthed in attics and basements, helping us better understand the nature and scope of the catastrophic events that led to so much misery in Europe and the near annihilation of Jews on the continent. Much less is known about the Holodomor, although the death count is enormous, nearly 30,000 Ukrainians dying daily at the height of the famine, and the engineering incontrovertible. This contrast is a stark reminder of the continuing need to uncover and reveal the history of Eastern Europe, kept hidden for so long under Soviet authorities.

Now that Ukraine has jumped onto our screens and into our awareness of global affairs, this is an important opportunity to learn, and in some cases, unlearn what we’ve come to know as history. In this ongoing process of enlightenment, the National Holodomor Memorial and the accompanying exhibit in D.C. is a meaningful beginning. We also have a growing body of work from modern European historians such as Timothy Snyder whose work specifically focuses on the back-to-back tragedies of Ukraine under Stalin and Hitler, both deeply rooted in the desire to colonize Ukraine’s richly fertile territory. Thanks to such scholarship, we are beginning to come to terms with the many misconceptions, deliberate and otherwise, as we work together to fill the many gaping holes in our knowledge of Ukrainian history, a history largely written by Russians often hostile to Ukrainians.

In light of this history, it seems that the sorts of concealments and distortions we’ve seen so prominently in today’s Russian invasion rhetoric that vilifies and demeans both Ukraine and Ukrainians has been going on for a long, long time. In fact, Putin’s famously professed views of Ukraine not being a real nation, or that Ukrainians are merely lesser Russians, reveals a paternalistic attitude that many Russians have held about the Ukrainian minority for centuries.

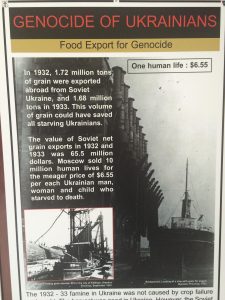

This attitude played a critical role in what we know – and don’t know – about the Holodomor, one of the most horrific events in Ukraine’s history. During the Soviet era, talk of it was strictly forbidden, covered up in the language of modernization, as a seemingly laudable goal by Stalin to collectivize agriculture in the

fertile territories of the Soviet Union. Later, in the waning days of the Soviet Union, document archives were opened, and the world began to learn of the systematic and premeditated inhumanity of Stalin’s brutal plan to suppress the Ukrainian nation and people, by making them work impossibly harder than ever, then depriving them of their entire harvest, their livestock, and finally criminalizing even the mere possession of food. I heard stories from my mother passed on by her father, who witnessed traumatized villagers being shot on the spot for having a sack of potatoes. No questions asked. This is how millions were slowly, quietly and ruthlessly starved to death.

Russia’s open era of glasnost is long gone, sadly. Instead, we see under the leadership of Vladimir Putin, a resurgent militaristic, imperial Kremlin that has no problem highlighting the good side of Stalin (as Federal Council Speaker Valentina Matviyenko did in a recent interview) or violently destroying Ukrainian territory or even killing Ukrainians. Stalin is again popular, and once again we're even back to the systematic denials of the Holodomor’s significance, cause, and any responsibility for the millions of Ukrainian deaths. These denials have taken on a distinctly nasty character since relations between Ukraine and Russia have taken a sharp nose-dive after Russia invaded Ukraine last year. In fact, as part of Russia’s propaganda war on Ukraine, state-run media have been attempting to use Holodomor denial to boost their campaign against Ukraine and the West more generally. It’s a kind of double gut punch, claiming Ukrainians’ defining suffering doesn’t really exist, even a "hoax," invented and perpetrated by neo-Nazis, who conveniently are also running the coup government in Kyiv. Such pronouncements just pour the proverbial salt into a deeply painful wound, one ingrained in every Ukrainian’s collective memory.

Others have analyzed the illogical and shameful attempts by Russia’s Kremlin-controlled media to deny Ukraine’s Holodomor. Cathy Young in The Daily Beast has a particularly good exposition of the issues. And there are many other articles at Radio Liberty and podcasts that have commendably taken the deniers to task.

Tomorrow's official unveiling of the National Holodomor Memorial in the US is a time to remember the millions of Ukrainian lives lost to hunger and lost to history. Perhaps had we known more of the truth of this dark period in Russia's and Ukraine’s history, we would have been in a better position to understand the mindset of Putin’s Russia today. This mindset differs little from that of Stalin or from the Russia of the Tsars for that matter, all rooted in colonial, paternalistic and hostile views of Ukraine and Ukrainians.

There is little doubt that Russia under Putin is trying to assert and maintain control of Ukraine. In fact, Putin's Kremlin is doing the same thing Stalin's Kremlin did to Ukraine, and for the same reasons; namely, Russia seeks to suppress a people who have expressed their will to be free, to have their own voice, their own government, and their own identity. In a recent talk, legendary journalist Marvin Kalb essentially argues that this is Ukraine’s cross to bear, cursed by its geography to remain within Russia’s orbit.

The story doesn't end but begins there. It's important to understand that for Putin, as in Stalin's day and for centuries, Ukraine has been fundamental not only to Russia's ambitions but its very identity. After all, what kind of Empire, or even Great Nation, would Russia be without Ukraine, where much of its history, heart and soul are located? Russians believe their civilization was founded in Kyiv (Kievan Rus, they call it). Quintessentially Russian greats like Chekhov, Babel, Gogol, Prokofiev, Bulgakov, Nekrasov, Akhmatova, even Solzhenitsyn (mother) are from Ukraine. You can see Russia struggling with these issues of identity when one of its most famous artists Ilya Repin had the renown painting of the Zaporozhye Cossacks writing a letter to the Turkish Sultan hidden as subversive at Tretyakovskaya Gallery. These identity issues – the blessing and curse of empires – are what Russia’s rulers have heretofore been unable to face, and as a result, they have continually resorted to assertions of dominance in aggressive and brutal ways. Russians, after Putin's reign, will eventually come to terms with their identity crisis, hopefully less defensively and less aggressively, once they recognize they don't have to define themselves by their perceived enemies, and begin to appreciate their own uniquely rich human capital.

In the meantime, Ukraine is moving forward. It has rejected its Soviet past. And Ukraine's assertion of an independent identity from Russia since the Euromaidan protests and revolution is probably the harshest rejection of Russia in its history, even more than during Stalin's era. Euromaidan was successful in ousting a Russia-friendly president, and the new Ukrainian government has succeeded in refocusing the world's attention to an unrepentant aggressive Russia. Although Ukraine may be struggling in many ways, Ukraine’s identity as distinct from Russia is not one of them. Today's distinctly Ukrainian Ukraine will struggle but will not be turning back to Russia anytime soon. Putin’s shameless seizure of Crimea followed by a destructive and tragic war in the Donbas has only solidified Ukraine’s determination to fulfill its European dream of dignity and self-determination. And though perhaps not loudly but certainly consistently, the international community fully supports Ukraine in this effort. The National Holodomor Memorial is an important reminder of just that.

BOOKS & ARTICLES:

- Applebaum, Anne. Red Famine: Stalin's War On Ukraine. New York: Doubleday, 2017.

- Cairns, Andrew. The Soviet Famine 1932-33: An Eyewitness Account of Conditions in the Spring and Summer of 1932. Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, University of Alberta, 1989.

- Commission on the Ukrainian Famine. Investigation of the Ukrainian famine, 1932-1933: Oral History Project of the Commission on the Ukraine Famine. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1990.

- Conquest, Robert. The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine. USA: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Davies, R.W. The Socialist Offensive: The Collectivization of Soviet Agriculture, 1929-1930. London: Macmillan, 1980.

- Davies, Robert William and S.G. Wheatcroft. The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931-1933. USA: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

- Dimarov, Anatoliy. A Hunger Most Cruel: The Human Face of the 1932-1933 Terror-Famine in Soviet Ukraine. Winnipeg: Language Lantern Publications, 2002.

- Dolot, Myron. Who Killed Them and Why? In Remembrance of Those Killed in the Famine of 1932-1933 in Ukraine. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984.

- Dolot, Myron. Execution by Hunger: The Hidden Holocaust. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1987.

- Gamache, Ray. Gareth Jones: Eyewitness to the Holodomor. Cardiff: Welsh Academic Press, 2013.

- Halii, Mykola. Organized Famine in Ukraine, 1932-1933. Chicago: Ukrainian Research and Information Institute, 1963.

- Hryshko, Wasyl. The Ukrainian Holocaust of 1933. Toronto: Bahriany Foundation, 1983.

- Kostiuk, Hryhory. Stalinist Rule in Ukraine: A Study of the Decade of Mass Terror, 1929-1939. Munich: Institut zur Erforschung der UdSSSR, 1960.

- Krawchenko, Bohdan. Social Change and National Consciousness in Twentieth-Century Ukraine. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1985.

- Lemkin, Raphael. “Soviet genocide in the Ukraine.” J. Int’l Crim. Justice 7 (2009): 125-130. [Reprint of original 1953 speech delivered in NY. Source: Raphael Lemkin Papers, The New York Public Library, Manuscripts and Archives Division, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundation, Raphael Lemkin ZL-273. Reel 3.] Available as a PDF at the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association website, UCCLA.CA.

- Luciuk, Lubomyr Y. and Lisa Greku (eds), Holodomor: Reflections on the Great Famine of 1932–1933 in Soviet Ukraine. Kingston: The Kashtan Press, 2008.

- Luciuk, Lubomyr Y. (ed), "Tell Them We Are Starving": The 1933 Soviet Diaries of Gareth Jones, in The Holodomor Occasional Papers Series, #2. Kingston, Ontario: Kashtan Press, 2016.

- Marcus, David. “Famine Crimes in International Law,” American Journal of International Law 97, no. 2 (2003): 245-281.

- Motyl, Alexander, "Deleting the Holodomor: Ukraine Unmakes Itself," World Affairs Journal, Sept.-Oct. 2010. http://www.worldaffairsjournal.org/article/deleting-holodomor-ukraine-unmakes-itself .

- Motyl, Alexander, "Remembering the Ukrainian Famine-Genocide," World Affairs Journal, Blogpost from December 13, 2013. http://www.worldaffairsjournal.org/blog/alexander-j-motyl/remembering-ukrainian-famine-genocide .

- Oleksiw, Stephen. The Agony of a Nation: The Great Man-Made Famine in Ukraine, 1932-1933. London: National Committee to Commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Artificial Famine in Ukraine 1932-1933, 1983.

- Plokhy, Serhii. The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine. New York: Basic Books, 2015.

- Procyk, Oksana, Leonid Heretz and James Earnest Mace. Famine in the Soviet Ukraine, 1932-1933: A Memorial Exhibition, Widener Library, Harvard University. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1986.

- Serbyn, Roman. Famine in Ukraine, 1932-1933. Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1986.

- Serbyn, Roman. "The Holodomor: Reflections on the Ukrainian Genocide," 16th Annual J.B. Rudnyckyj Distinguished Lecture Friday, November 7, 2008. Available at http://www.umanitoba.ca/libraries/units/archives/media/Lecture_XVI-Serbyn.pdf .

- Snyder, Timothy D. Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books, 2010.

- Young, Cathy, "Russia Denies Stalin's Killer Famine," The Daily Beast, October 31, 2015, accessed November 25, 2017. http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/10/31/russia-denies-stalin-s-killer-famine.html?via=mobile

WEBSITES:

- http://www.holodomorct.org/

- http://www.historyplace.com/worldhistory/genocide/stalin.htm

- http://judicial-inc-archive.blogspot.com/2010/08/bolshevik-famine-seven-million-dead.html

- http://www.ukrainiangenocide.com/

- http://www.ukrainiangenocide.org/

- http://www.unitedhumanrights.org/genocide/ukraine_famine.htm

- http://www.faminegenocide.com/

- http://www.infoukes.com/history/famine/

- http://www.faminegenocide.com/resources/facts/

- http://gis.huri.harvard.edu/historical-atlas/the-great-famine.html

FILMS:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=awxHKqEquco&sns=tw

Bitter Harvest "a 2017 romantic-action drama film set in Soviet Ukraine in the early 1930s during the Holodomor Genocide starvation policy that killed millions of Ukrainians under Stalin's forced collectivization of all farms and businesses owned by Ukrainians. The film was directed and co-written by George Mendeluk with Richard Bachynsky Hoover, based on Bachynsky Hoover's original story. The film stars Max Irons, Samantha Barks, Barry Pepper, Tamer Hassan and Terence Stamp. The film is produced by Ian Ihnatowycz, Stuart Baird, Mendeluk, Chad Barager. Dennis Davidson, Peter D. Graves and William J. Immerman served as executive producers along with Richard Bachynsky Hoover." (Source: Wikipedia). Official trailer #1: