Tomorrow, some will celebrate the anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution, and on Monday, a much smaller number will mark the anniversary of the Third Reich, a conjunction of dates that again prompts many to compare these two systems and their evils.

In a Rufabula commentary today, Russian regionalist Vadim Shtepa says that “it is useful to recall an ethnical distinction” between the two totalitarian systems of the 20th century “not of course with the goal of justifying either of these regimes” but rather because interest in both remains so high.

When the OSCE in 2009 suggested that Stalinism was like Nazism, many Russians were furious, at least in part because their government considers itself ‘the legal successor of the USSR’ and as a result, “the exclusively Soviet treatment of the events of World War II and the preceding period even intensified.”

To be sure, Russian academic historians and publicists continued to be allowed to criticize certain excesses in that period, Shtepa says, but “on the whole, [the Stalinist system] is considered… ‘an heir’ to the Enlightenment with its progressive stance, rationalism and humanism.”

“Compared with this,” he continues, “European fascism (in the broad sense including all the rightwing anti-communism regimes of that era) is treated as ‘an absolute evil.’” Beyond question, Shtepa says, “Nazism from an ethical point of view really can be called [that] because “a regime based on the destruction of people of other nationalities from the outset was condemned, if humanity wanted to remain humanity.”

“But all the same, this absolute evil was honest. What it professed, it carried out,” Shtepa says, unlike the case with Bolshevism were there was “a gigantic gulf between its declarations and the real outcomes.”

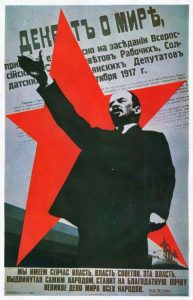

That can be seen if one considers the three famous decrees Lenin issued immediately after coming to power in October 1917, promising the peoples of Russia (1) peace, (2) land, and (3) the right of self-determination. In all three cases, the Bolsheviks promised one thing but carried out a very different policy.

“Peace”

The Bolsheviks promised a people tired of war “’a just and democratic peace’ without annexations or reparations.” But as soon as they had power in their hands, they showed that they were not committed to peace; and in 1920 the Red Army invaded Poland. Fortunately, thanks to the Miracle on the Vistula, it was defeated and spreading the revolution by war failed.

“Land”

Lenin also issued a decree promising to give land to the peasants, the Russian regionalist continues. But in fact, again, they quickly took back what they promised and drove the peoples under their control into collective farms, killing all those who resisted or even were assumed to resist this action.

“The right of self-determination”

The third Bolshevik decree, “the declaration of the rights of the peoples of Russia” had a similar fate. It proclaimed “the equality and sovereignty of the peoples of Russia, [their] right to free self-determination up to separation and formation of independent states, the elimination of all national and national-religious preferences and restrictions, and the free development of national minorities and ethnographic groups.”

“Had this declaration been realized,” Shtepa says, “it would have meant the total overcoming of the Russian imperial tradition. However, in reality, the Bolsheviks had completely different plans which called for the restoration of the empire but on different ideological foundations.”

Lenin was forced to recognize the independent of Finland in December 1917, but he immediately armed the Finnish Red Guards in the hopes of re-uniting that country with “’the republic of the soviets.’” And he sent troops against Karelians who took the declaration of their rights seriously.

In this way, Shtepa says, “having begun with a struggle against ‘tsarist imperialism,’ the Bolsheviks ended with the restoration of a centralized empire – only in much harsher forms.” The russification of national minorities intensified, but ethnic Russians “hardly won anything as a result.”

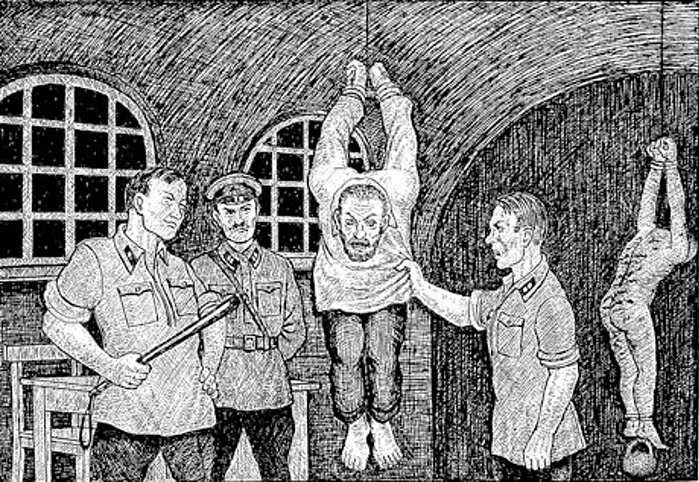

In 1936, Lev Trotsky, already a political émigré, published his book, “The Revolution Betrayed,” in which he accused the Stalinist regime of “’bureaucratic degeneration.’” But in fact, Trotsky himself was the originator of many of that regime’s worst features, including the concentration camps.

Here, Shtepa says, is the “sharp contrast” between what the Bolsheviks promised and what they delivered, the conversion of the country into “a totalitarian dictatorship unprecedented in world history.” Not surprisingly, this frightened the Europeans, and “in essence, European fascism became reaction to the cynical lie of the communists.”

Many historians who speak of fascism as an absolute evil, Shtepa concludes, “do not see or do not want to see this cause and effect linkage. Buchenwald is in no way better than Kolyma. But without Kolyma there wouldn’t have been a Buchenwald.”