Vladimir Putin has nothing positive to offer toward the resolution of any of the crises he has helped create, but he has succeeded in getting a meeting today with US President Barack Obama because the Kremlin leader has shown himself capable of causing ever more crises, something others want to prevent if they can.

That diplomatic strategy may get Putin the international attention Putin craves and likely needs to shore up his position at home as a leader who never makes mistakes, Aleksandr Golts suggests in “Yezhednevny zhurnal,” but it is a profoundly dangerous one not only for the world but for Russia and Putin himself.

“There is no doubt,” the Russian commentator says, “that Moscow in the near future will have to think up new ‘negative stimuli’ in order to force Washington to direct its attention to [Putin].” Among the most probable would be the placement of tactical nuclear warheads in Kaliningrad and the forwarding basing of Tu-22M3 strategic bombers” on Russia’s frontier.

But if the Kremlin does so, it would be in violation of various arms control treatiesf and that would lead it into the kind of arms race “which destroyed the USSR” and which today’s Russia is not capable of taking part in, however many bombastic statements its officials make, Golts say.

And that means, whether people in the Kremlin or people in the West know it, that “for the time being, “no ‘negative stimuli’ have been found” that can be effectively deployed on Putin’s behalf. What is disturbing and “dangerous” is that “the Kremlin is concentrating exclusively” on such things, something that makes it ever less predictable and less reliable.

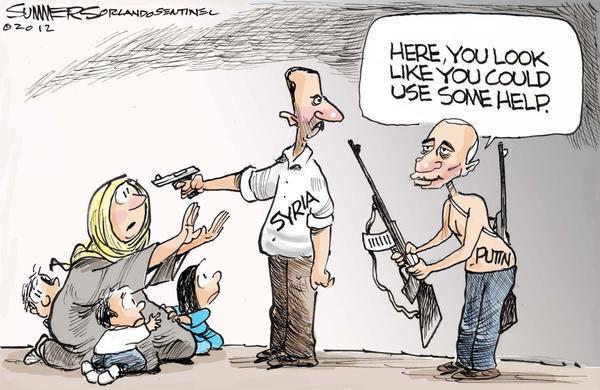

In a blog post, Russian commentator Lilia Shevtsova extends this argument. She asks rhetorically: “Do they understand in the Kremlin that the Syrian blackmail” Putin has used to get meetings in New York “has made Russia into an extra-systemic player and an international leper?”

“From now on, Russia is an adventurist state,” she continues, because “the Kremlin by its surprises shows… its complete lack of responsibility which creates the impression of despair and of a lack of any way out,” an impression that may be hidden for a time because of the way in which others must treat a nuclear power.

“One must not ignore it, one must calm it and at the same time build a self-defense against its new initiatives,” she argues. Or as some Western observers put it, “If the Russians want to get involved in the Syrian mess, we won’t interfere” because “apparently suicide is embedded in their genetic code.”

Another Russian commentator, Leonid Radzikhovsky, fully agrees. He suggests that Putin has suffered two serious defeats already this year – one in Ukraine where his Novorossiya efforts have come to nothing and a second with China where his hopes for an alliance have been dashed.

The Kremlin leader faces more problems ahead: the Boeing and Litvinenko case and the end of the Minsk process. And consequently, Putin is casting about not for ways to address the problems he faces now but to create more problems in the hopes that he will be able to intimidate others into giving him the victories or simulacra of victories he craves.

In a commentary in advance of Putin’s meeting with Obama and speech to the UN General Assembly, Russian journalist Semyon Novoprudsky says that these are momentous times for Putin because “never since the end of the USSR have the political positions of a Russian president in the world been so weak.”

Whatever he and his supporters think, Putin has “outplayed himself” and “weakened Russia, whose role in the international economy has already fallen below three percent of the total and continues to decline. Countries with such economic potential even if they have nuclear weapons cannot play the role of world gendarmes,” even if some in Moscow “dream” of this.

The wars the Soviet Union carried out far from its borders were attacks, but Russia “in Ukraine and now in Syria is conducting a deeply defensive war with a single goal: to make it so that the current Russian regime can remain in power as long as possible,” even if that results in the destruction of the Russian economy.

Given this desperate situation, Putin will be prepared to sacrifice anything, including Bashar Assad, if that is the price of saving himself. His policies have led to the expulsion of Russia from the G8, a reduction in its role in the G20, the collapse of trade with China and of the ruble, and the elimination of the opportunity for Russian firms to get loans in the West.

“Russia,” Novoprudsky continues, “is in political and partially in economic isolation,” and despite what some think, it won’t escape that if prices for oil go up. That is because Russia’s crisis is “not economic but political,” the “direct result of Russia’s efforts” to use foreign expansion to mask internal collapse.

Putin has to hope that his calls for an international coalition against ISIS will gain him support and allow him to come back into the international fold because “any independent military actions by Russia in Syria will lead to new sanctions” and the situation of the Russian economy will become even worse.

In this situation, Putin will use chauvinist propaganda to keep his population in line and fear to ensure that the elites around him will remain loyal. He doesn’t have any other resources, whatever he may think. But he will do whatever he thinks necessary to remain in power because above all Putin is afraid of “repeating the fate of other presidents who have been overthrown.”