Julia moved to Kyiv to go to school. She left her home in western Ukraine to attend a university in her nation’s capital city. Like other young Ukrainians, her focus was on the future: carving out a career, working hard for a scholarship, and maybe even traveling abroad. She didn’t go to Kyiv to seek out a revolution, or to watch a war unfold. She didn’t leave home to fall in love.

Filmmaker Roxy Toporowych didn’t initially come to Ukraine to tell Julia’s story. In 2013, Roxy applied for a highly competitive Fulbright grant to participate in a community-based film project. Three months after submitting her application, Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) in Kyiv was full of student protesters. Images of clouds of smoke rising from burning tires appeared in news articles. Ukraine found itself in the midst of a revolution. Six months later, Roxy found out that her Fulbright had been awarded.

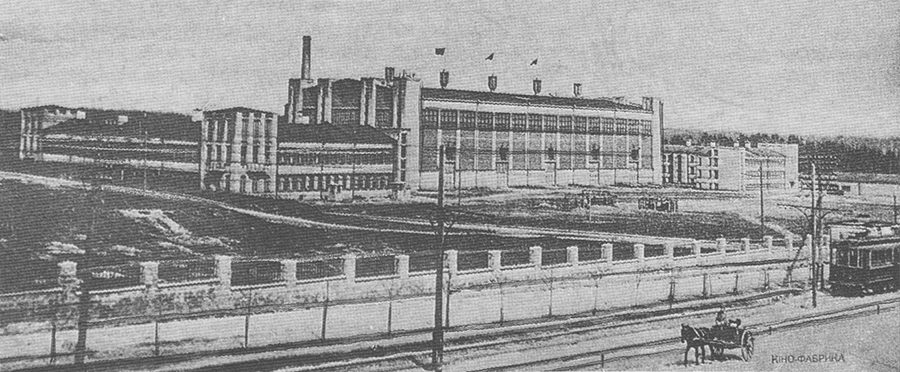

In September 2014, Roxy Toporowych stepped off a plane at Boryspil International Airport. She entered a city where fresh graffiti covered cracked cement walls and Lada cars were parked diagonally on sidewalks. According to her, “The place I applied to had become a completely different country, and the project I applied with no longer fit.” When Roxy first applied for the Fulbright, her documentary-driven project was titled “The Storytelling Experiment” and it was to be made in conjunction with the Dovzhenko Film Studios in Kyiv. This studio is in and of itself a relic from Ukraine’s cinematic history.

Construction of the site began in 1927, after Ukraine had been restructured into part of the Soviet Union. It took two years to build, and in 1929, became the largest film studio to date in Ukraine. Originally called the All-Ukrainian Photo-Cinema-Directorate, the studio was later named after one of Ukraine’s most famous film directors, Oleksandr Dovzhenko. He is credited with being not only one of the best Soviet filmmakers, but one of the pioneering masters of the silent era. Critics consider his 1928 film Zvenyhora to be the first truly Ukrainian film. It mixes traditional folk themes with avant-garde cinema methods. This film was also the first in his “Ukraine Trilogy,” which includes the classics Arsenal (released in 1929) and Zemlya (1930).

The Dovzhenko era helped to establish Ukraine as a powerhouse for Soviet filmmaking. At its peak, Ukraine was responsible for thirty percent of all of the Soviet Union’s film production. When the Soviet Union collapsed, the nationalized Ukrainian film industry collapsed with it. The Dovzhenko Film Studios in Kyiv went from communist state ownership to relying on a new capitalist government for funding. As part of this transition, it went from producing fifteen full-length productions a year to just three. This is the condition that Roxy Toporowych found the Ukrainian studio in when she got to Ukraine.

Before applying for the Fulbright and traveling overseas, Roxy had already acquired a passionate interest in Ukrainian stories. She grew up in Parma, where Ohio’s largest Ukrainian community resides. Roxy was thirteen years old when she started making Ukrainian-inspired movies with a home video camera. Filmmaking led her from Cleveland’s suburbs to New York City, where she completed a Bachelor’s degree in Film and Television at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. After working on the sets of major productions, including Saturday Night Live

and Law and Order, Roxy made her directorial debut with Folk!, a documentary about Ukrainian folk dancing in North America. The film took eight years to make. It screened at several venues in the United States and Canada. Fittingly, Roxy brought the completed version of Folk! to Ukraine in November of 2011, where it was received with enthusiasm at Kyiv’s first American Independence Film Festival.

When Roxy returned to Kyiv to commence her Fulbright project, another documentary was her goal. Over the last year, Roxy had found herself surrounded by cab drivers and students, hipsters and babushkas, fruit vendors and soldiers, farmers and professors, all from different philosophies but united in the hope for a better future in Ukraine. After seeing the effect the Maidan revolution has had not just on global politics and economics, but on the personal lives of Ukraine’s inhabitants, Roxy realized the scope of her project had to change. According to Roxy, “There are so many stories and there is so much information to get across that I felt the best way was to take the best of many parts and to write a script, instead of shooting a documentary.”

Roxy is currently in Kyiv, preparing to shoot a narrative feature-length film called Julia Blue. Its characters are inspired by the people she met while searching for documentary subjects that were going to be part of her original Fulbright project. The story is about Julia, of course. And about Ukraine. And love. And war.

Julia Blue will star two Ukrainian actors: Ivanna Sakhno as Julia, a western Ukrainian university student, and Dima Yaroshenko as English, a soldier from the eastern front. Casting these characters was part of Roxy’s adventure for making the film. She says, “I literally did things to find my cast I never thought I would do - chasing people off trolleys, letting them audition by staring at me. (Yes, that was one audition!) I held casting sessions all over the city [Kyiv], met the stars of Ukrainian theatre and finally, after all that, found Ivanka by chance at a dinner party.” Roxy’s cinematographer, Sashko Roshchyn, saw Dima in a play a year earlier and said, “You have to see him.” After four auditions, Roxy cast her lead actor.

With Julia being from the west, and English coming from Donetsk, the story is not just about an isolated region in Ukraine. Its characters are a composite of the whole territory. Because of the linguistic variations that sweep from west to east, Roxy decided to write the script in English. And in Ukrainian. And in Russian. When talking about the script, Roxy nervously laughs and calls it a fun challenge. In order to capture the complex reality that is going on in the country today, Julia Blue

will be a trilingual film. Selecting just one language would be an inaccurate and diluted version of Ukraine’s current demographics.

As part of the film’s crew, Alexey Karpenko of MKK Films will be helping Roxy to produce Julia Blue. He is part of the team that created the Cannes Film Festival award-winning movie, Plemya (“The Tribe”), directed by Miroslav Slaboshpitsky.

Plemya is worth mentioning because it is one of Ukraine’s most recent success stories. Although filmmaking in Ukraine is stifled--it is a whisper of what it used to be--there are a few films that have reminded the international community that great movies can still come out of Ukraine. The drama Povodyr (“The Guide”) and The Russian Woodpecker, a documentary about Chernobyl, have also captured critical acclaim at film festivals. These films point to what Ukrainian cinema could look like today.

Unfortunately, this is what Ukrainian cinema looks like today. Movie-goers in downtown Kyiv can choose from the American blockbusters Southpaw, Self/less, or Nightcrawler.

French film options include the thriller La Prochaine Fois Je Viserai Le Coeur or the comedy-drama Papa ou Maman. Fans can even watch the 2012 Canadian sex comedy My Awkward Sexual Adventure. And for those with enough money, and the desire to see a twenty-foot tall Tom Cruise save the world (again) viewers can catch Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation at an IMAX theater.

Artists like Roxy Toporowych are anxious to help Ukraine’s cinema scene step out from the shadows of its Soviet past. For Roxy, it is important to make Julia Blue now. Ukraine’s complicated past is meeting its uncertain future face-to–face. The Maidan revolution did not only happen in a square in Kyiv; it echoes in the valleys of the Carpathians and in the factories of Kharkiv, on the streets of Lviv and the shipyards of Mykolaiv, in the wheat fields of Zhytomyr and the mines of Donetsk. There are so many stories to tell through film. And for Ukraine, it is time to invigorate its rich cinematic history.

[hr]Julia Blue will be filmed in Ukraine's capital Kyiv and the scenic Carpathians. These are some pictures of the sites that have been selected: