It appears that the Great Patriotic War was chosen to explain the war in Donbas both to Russians and Donbas's local pro-Russian population on a mythical level, as it is a powerful symbol that appeals to broad audiences, one that is still alive in the collective memory. It is unlikely that in so short a time a new symbol with equal power could be invented in order to mobilize to war so many people. An epitomizing episode for this is the robbery of the Great Patriotic War museum in Donetsk on 9 May 2014, when armed representatives of the "DNR" broke in and stole rare weapons from the collection, claiming to use them in the fight against "fascists attacking their land."

Perhaps one of the best proofs that Russia is in a state of war with Ukraine is that its media is functioning based on the laws of a time of war, although at times it's not clear who the enemy is: either concrete Ukraine or the abstract West. Wartime media has a specific goal: to raise the battle spirits of your own people, create the image of an enemy, and demonize and dehumanize your opponent. It is the successful accomplishment of this task that has motivated the residents of Donbas to take up arms, and thousands of Russians to travel to Donbas to fight, despite the contradiction between the official version of events, where Russia is not a party to the war, and the messaging of Russian central media stations, which implies that it is definitely at a war on a territory that it considers its own, and defending its own people. A recent interview on Radio Svoboda with Manas, a Kyrgyz mercenary that spent 6 months fighting against the Ukrainian army as part of Russia's hybrid forces in Donbas, gave a vivid example of the mobilizing power of the Great Patriotic War myth: Manas came to Donbas to fight against fascists. After 6 months he discovered there were none there and returned.

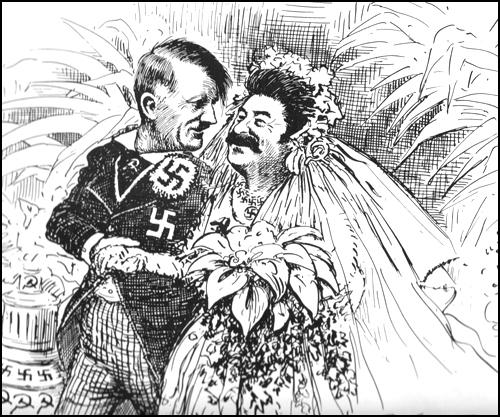

In operating by the laws of war, Russian media copies elements of both Soviet and German World War II propaganda.

|

Country of origin, target audience today, and function |

Propaganda elements that are used in war with Ukraine |

|

USSR. Target: Donbas; Function: boosting spirits of own fighters |

|

|

USSR. Target: Donbas; Function: creation of image of the Enemy |

|

|

Nazi Germany. Target: Russians. Function: gather support for leader and war |

|

The image of the enemy was constructed, in the words of Yury Saprykin, ex-editor of the Russian outlet Afisha, ingeniously: the conflict was translated to the language of the Great Patriotic War. We are not dealing with a revolution, anti-government demonstrations, but with a “fascist junta” that sends its punitive squads to the East. A person that has encountered these expressions can’t watch events from the distance anymore; he finds himself inside the history of a sacred war, where what is good and evil it is quite clear already on the lexical level. He finds himself inside a textbook where “our guys” battle the fascists. Denying this image of the world equals being a fascist collaborator. This is very convenient for burying the image of Maidan in a sea of fascist associations. A google search number of cases where "Ukraine" and "fascism" are mentioned together reveals that the number doubled after Euromaidan. The primary purpose of this association, according to wartime propaganda logics, is instill hate towards the "enemy," i.e. the Ukrainian army and their supporters, by making them appear as inhumane monsters.

A google search of hits for "Ukraine fascism" in the English and Russian languages from 2012-2015. 22 February marks the date when then pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych fled Kyiv and the protesters took control of Kyiv.

Apart from making the enemy appear horrible, devious, and superpowerful, the enemy also needs to be made weak and ridiculous, to quell fear and facilitate killing. This is done in mainstream Russian media by ridiculing Ukraine and its leaders, and in social media by employing a vast number of slurs, the function of which is to convince oneself that the enemy is not human at all. "Ukrs,""ukrops,""banderites" are examples of such slurs.

Social memes, widespread in pro-Russian social media groups, follow the main principles of war propaganda, sometimes tapping into the Soviet legacy of war propaganda.

Example of the "horrible enemy" image in Soviet times (top) and modern Donbas (bottom)

The "ridiculous enemy" image in Soviet WWII propaganda (top) and the modern Russian war against Ukraine (bottom)

The memory of the Soviet contribution to the victory in the World War II and its skewed interpretation by Soviet historiography has been employed in propaganda purposes. Examples range from a staged invasion of Europe in a Russian Sunday show (following a story with the Polish president suggesting to celebrate the ending of WWII on Poland's Westerplatte, attacked on 1 September 1939 by the Red Army, instead of Moscow) to the "Topol isn't afraid of sanctions" Tshirt PR campaign to soften the psychological effect of sanctions imposed on Russia, to the infamous journey of the Night Wolves biker squad to Berlin on 9 May 2015. Ultimately, these stories serve one purpose: to instill a feeling of military might and a special right of the nation that saved the world from fascism to meddle in geopolitical affairs of its neighbors.

A particular danger of this Great Patriotic War narrative in mass media lies in unconscious aspirations of the Russian population to live in this construed reality. The growth of aggression taken together with a refusal to accept reality in Russia can be explained by official propaganda, but to be really effective it must be grounded on the subconscious attitudes of the population. M.Yampolskiy filters out two psychological processes that facilitate the loss of reality: projective identification and resentment. With the help of projective identification, which is observed during the rise of fascism, the bleak reality carrying weakness, poverty, and humiliation, can be escaped by denying one's own ego and associating with a strong leader or group. Resentment stems from the inability of ordinary Russians to change their everyday lives and the life of their country and the confusion of the whirlwind of events which they are powerless to influence, facilitating an escape into an imaginary world where the unfortunate reality is denied. In reliving the Great Patriotic War 70 years after its end on a daily basis with the help of mass media narratives, Russian society receives everyday reinforcements to the growth of the fascisation of Russian society and the cult of its totalitarian leader.

[hr]Other proceedings from the conference "Usage of the topic of WWII in the Russian political discourse":

Memory of the Great Patriotic war in Russia’s expansionist policy

Occupation of Crimea repeats Latvia’s occupation by USSR

The “Great Patriotic War” as a weapon in the war against Ukraine

Russian media operates by law of war, tapping into Great Patriotic War myth

Soviet myths about World War II and their role in contemporary Russian propaganda