European scholars now recognize that no one can understand the present without a thorough understanding of the Middle Ages, and they are beginning to include in that understanding the Golden Horde, as a recent conference in Leiden shows, according to Rafael Khakimov, the vice president of the Tatarstan Academy of Sciences.

Unfortunately, he continues

, Russian scholars are not in a good position to help them. On the one hand, the study of the past remains extremely politicized. “Heaven forbid that you find anything positive in Tatar history… or anything negative in Russian history.” In the former case, you’ll be denounced as a separatist; in the latter, as “an enemy of this branch of humanity.”

And on the other hand, Khakimov continues, “the next generation of historians will not soon appear: they have ceased to be trained. No one apparently needs historians or an honest history. No one welcomes the latter,” especially if it leads to the explosion of old but very useful “myths.”

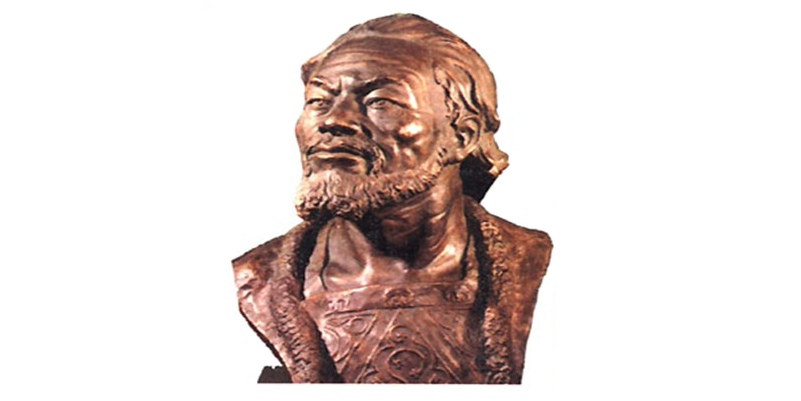

But there are historians within the borders of the Russian Federation who do know the history of the Golden Horde and who are not afraid to speak the truth or share it with the Europeans, and Khakimov, the longtime head of the Kazan Institute of History and former advisor to Mintimer Shaimiev, is perhaps the most eminent and outspoken.

In a commentary this past weekend for Kazan’s “Business-Gazeta

” in which he discussed his presentation to the Leyden conference, Khakimov says that “all of Eastern (and part of Central) Europe in one form or another depended on the Golden Horde,” although few in these regions know the details.

Relations were warm: in 1272, Nogay took as his wife the Byzantine princess, Yefrosinya, and thus the third wife of khan Uzbek became the daughter of Emperor Andronik III. Given the stress Russian historians put on the marriage of Ivan III with Sofia Paleologue who supposedly brought the symbol of empire, the two-headed eagle, one should not neglect this other marriage.

“At the time of the flourishing of the Golden Horde,” Khakimov continues, “Byzantium was already the ‘weakened old lady,’ as one of the Russian historians expressed it. The destruction of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade in 1204 undermined the empire, and it finally fell to the Turks in 1453.

Byzantium thus could not be “a positive model” for the rising Russian state, he argues, adding that “in general, empires are not build by the emanations of spiritual forces. For their rise are needed concrete structures, experience of conducting large-scale state affairs, contemporary arms, a financial system, an economy and the ability to support a large army.”

“All this” was true of the Golden Horde at that time, the Kazan historian says, and that “became the source for the construction of the Russian empire.” The notion of Muscovy as the Third Rome never was “about a mechanism of the construction of the empire.” Instead, it was only “about the ambitions of Russian monarchs who pretended to the inheritance of the Golden Horde in Orthodox packaging.”

The Tatars “participated in all political events in the Balkans up to the 14th century,” and thus played a role in the history of Bulgaria, Hungary, Serbia, Romania and Moldova. They played a no less important role in Poland and Lithuania both in terms of state-to-state relations and as the source of the Lithuanian forces who occupied Moscow in the Time of Troubles.

“Of course,” Khakimov says, “the influence of the Horde on Europe was relatively brief, about 150 years long, but it was significant” and cannot be reduced to attacks or pressure given that there were clearly established borders with customs collections and the like.

All this has been obscured by the launch of the Crusades against “the agents of Satan and servants of Tatarus” and more recently by the work of “certain Russian historians” who like to view as opposites the Russians and the Tatars. That Roman paradigm allows them to view themselves as part of Europe and assign the Tatars to backward Asia.

But those who make or accept that argument should remember that “Europeans in those times considered the Russians as born Tatars, and on their maps, designated Muscovy as ‘Moscow Tataria’ in contrast to Novgorod Rus. In fact, the Russians are no more European than are the Tatars.”

“The image of the Tatars as fiends has long been part of the sub-consciousness of Europeans,” the Kazan historian says. But the Leiden meeting gives him hope because “changes in public opinion in the West always begin in the universities where scholarly studies are prepared, on which journalists and the media then rely.”

“And only after several Hollywood films can one count on a change in attitude toward the Tatars,” Khakimov concludes.

Related:

- Symbolic expansion: how Putin annexes history, not only territories

- Anna of Kyiv, the French Queen from Kyivan Rus

- How Moscow hijacked the history of Kyivan Rus’

- Kings or Princes? Why Do the Titles of Rusian Rulers Matter

- Ukrainian conflict is between ‘heirs of Kyivan Rus’ and ‘heirs of Golden Horde’

- Princess Olha of Kyiv: a golden page in Ukrainian history

- Ukraine and Russia “share a long and common history” FAQ

- Stolen ancient viking’s sword from the dawn of Kyivan Rus comes back home to Ukraine

- Ukrainian parliament mulls requiring officials to call the Russian state ‘Muscovy’

- Why there are Muslim crescents on Orthodox crosses in Moscow but not in Kyiv