Russia’s problem is not Vladimir Putin but rather that “the special services have begun to rule that country and to transform it “into one large special service and its activities into one large special operation,” something even Stalin never permitted, according to Yevhen Holovaha, deputy head of the Kyiv Institute of Sociology.

This is just one of the conclusions the scholar offers in the course of a wide-ranging interview published today on the occasion of the first anniversary of Putin’s acknowledgement of the use of Russian forces inside Ukraine, about conditions in Ukraine, and in the Russian Federation.

According to Holovaha, the last year in Ukraine’s history is most similar to the period of the Ukrainian Peoples Republic after 1917. Then too, Ukrainians wanted “dignity and independence but got a tragedy. Now is also a tragedy,” but whether it will be an “optimistic” one as some say or not depends on whether Ukrainian leaders can learn from their mistakes.

They do not have much time, he argues, because “if in past years we could allow ourselves to experiment, now there is no such possibility.”

That does not mean that Ukraine is about to disappear from the map of the world, as some fear. “Ukraine will continue in some form.” But the question is “in what borders, with what kind of a government and in what form?" Putin’s goal is to marginalize it, and such “a marginalization of Ukraine is the worst prospect.”

The past year has led to a rise in civic activism and volunteering, and it has not "led to a final disappointment” nor to a situation in which there would be a mass rejection of the ideals of the Maidan. One can only be glad about those things, even if they are in many ways the product of war which inevitably consolidates a society.

But, he continues, at the same time Ukrainians are “at the edge of nervous exhaustion,” and the level of optimism about the future has fallen significantly since last summer: Polls show this level down by 20 percent, the sociologist says. And both the deepening economic crisis and the shortcomings of the government are only making that worse.

Holovaha said that when he learned that the Ukrainian revolution was “a revolution of dignity,” he immediately observed that “dignity costs people very dearly.” Those who insisted on it in tsarist and Soviet times, paid heavily for doing so. And one must recognize that people cannot live on dignity alone; they need other things are to survive.

The Ukrainian government since the Maidan “unfortunately” has not been more open than was its predecessor, Holovaha continues. “There is no normal conversation with its citizens, with us even today things are absolutely Soviet as far as the openness of the state is concerned.

The sociologist says that he understands how difficult it is for leaders raised in the Soviet past or even the post-Soviet period to change their ways of doing business, but what is a particular matter of concern, he suggests, is that many of the new people who have entered the government have assimilated these earlier values rather than introducing new ones.

But the situation in Russia is much worse. “There is nothing new in the state system of present-day Russia. It is entirely a throwback to the Soviet model,” with its imperial schemes, symbolism, mass psychology, and the like, he says. That has allowed Russia to maintain the social order, but it requires enemies and “absolutely contradicts” the European path Ukraine has chosen.

Russia always was and always will be “imperialist and chauvinist,” Holovaha says, regardless of who is in office. The only question is how many resources it has to devote to those goals. When it is rich, “it will continue expansion … when it is poor and weak, it will gather its forces and not try to change borders.”

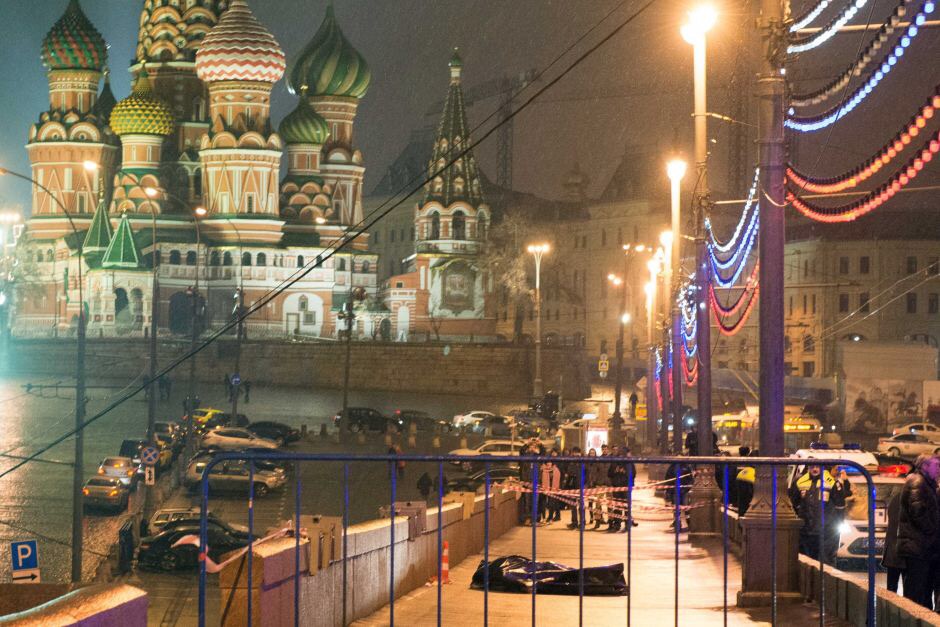

The murder of Boris Nemtsov, he suggests, was one of a series of “ritual murders on symbolic dates. If you recall, Anna Politkovskaya was killed 'on Putin’s birthday.' I believe,” Holovaha continues, “that the murder of Nemtsov on the eve of an anti-war march was no coincidence.”

As to the possibility that Russia will disintegrate into several republics, the Kyiv sociologist says, the threat exists, although it is far from clear whether Ukrainians would benefit from it and Ukrainians should be skeptical about anyone who suggests this or any other outcome is “’inevitable.’” Such predictions should not be taken seriously.

Regarding leadership, he says, there is no question that Putin is a leader. But he has done little more than rely on “prejudices, stereotypes and xenophobia.” That almost always works, has given him an enormous popularity rating and the chance to do whatever he likes as far as the Russian people are concerned.

As for Poroshenko, Holovaha says, he is “a transitional leader” in “a transitional time.” So far, he has pursued a policy of “maneuvering without definite successes and without an explanation of his motives and goals.” Given the challenges one can understand why, but to be successful he will have to move beyond such a tactical approach.