Those who support Vladimir Putin and those who oppose him overestimate the Kremlin leader, Vitaly Portnikov says, with the former assuming there is nothing he cannot do and the latter explaining away their own shortcomings and failures by making the same assumption.

As a result, the former assume that whatever the Kremlin leader does will work out as he projects and the latter fail to recognize his fundamental weaknesses and the ways in which he and his aggressive policies can be successfully countered, the Kyiv analyst says.

Among both groups, Portnikov writes, this faith in Putin has become almost “religious” and thus is neither questioned by those who hold it or challenged by those who don’t. But if one looks at Putin’s domestic career and what he has done to Russia as a result of his adventurism in Ukraine, it is clear that such “religious faith” in him is misplaced.

Portnikov argues that “the history of the political career of Vladimir Putin is the history of unachieved desires and political defeats” and that he “has won out only when there were more powerful, influential and strategically thinking people standing behind him. In all other cases,” he continues, Putin “could not realize his ambitious plans.”

And the Kyiv analyst argues that in the case of Ukraine, Putin not only is constrained by the presence in his own regime of many who do not agree with him and that their number will only increase as the costs of his actions for Russia rise and his inability to subordinate Kyiv to his will become more obvious.

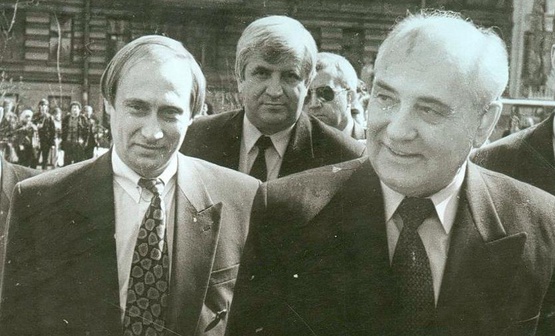

As this happens, Portnikov argues, it will be clear to all that Putin resembles ever more closely Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev “who voluntarily surrounded himself with those who secretly” and then quite openly in August 1991 “wished him ill” and whose actions at that time led to the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Indeed, the Kyiv analyst suggests, “Putin is repeating the path of one of his predecessors in the Kremlin with photographic exactitude.”

Portnikov is likely overstating the possibilities for a coup d’etat in Moscow at least at present. Putin is no political genius, but he is a very clever KGB officer who knows how to prevent such things far better than Gorbachev ever did, and he has successfully mobilized the Russian population in ways that Gorbachev was never able to do.

But while that may be the case, Portnikov’s central argument here should not be dismissed as a result. It is clearly true that Putin has managed to convince both his supporters and his opponents he is invincible, with the former supporting him because of that and the latter fearing to take strong actions to oppose him and thus engaging in appeasement.

At the same time, it is also true that Putin’s apparent strength is in fact an indication of his weakness: He cannot afford to lose even once because if he does, it will become clear to all that he is like the little man behind the curtain in “The Wizard of Oz,” not the all-powerful maestro so many appear to believe him to be.

To ensure that Putin’s aggression in Ukraine does not stand and his drive to impose fascism in Russia does not succeed, Putin must suffer a loss and be seen to suffer it rather than continue, because of the fecklessness of Western leaders, to push forward. Like other bullies, once Putin loses even once, the faithful will scatter both in Russia itself and in Western capitals.