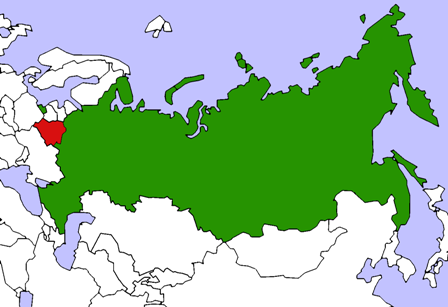

By his bombast and aggression, Vladimir Putin has destroyed “what was even a year ago called the post-Soviet space, an area which even then existed largely by inertia as an appendage of Russian ambitions” rather than as an expression of the desires of the countries included within that designation, according to Oleg Panfilov.

Panfilov, who is now a professor at the Ilii State University in Georgia, argues that the only thing “unifying the former Soviet republics” has been Russian propaganda and “a certain number of people who still dream of the revival if not of the USSR than of something like it.”

And both the propaganda of that idea and the number of people willing to accept it has grown with the deterioration of the economies in many of these countries. But despite that uptick, few in either the governments of these countries or their populations think that Putin’s revanchist project would be good for them.

“Putin’s empire sooner or later would have died a natural death as all empires have disappeared,” Panfilov says. But his “’Ukrainian adventure’” accelerated its demise because it showed what Moscow was really about, something that became for many “if not a discovery than a revelation.”

That the situation should have changed in Ukraine will come as no surprise to anyone, but that it has changed in every single one of the former Soviet republics and in the same direction may, from Central Asia to the Caucasus to the West, as the Georgia-based Russian analyst makes clear.

In Central Asia, people have come to understand that “Putin’s ‘Russian world’ is the ideology of nationalism, chauvinism and often open fascism,” that Russia has nothing to offer Central Asians except gastarbeiter cash transfers and increasingly not even that, and that they must look elsewhere for their futures.

In the Caucasus, Azerbaijan and Georgia are already independent players, and Armenia, which many have assumed would remain under Moscow’s control because of the Karabakh conflict is slipping away, the result of the murder of an Armenian family by a Russian sergeant and the heavy-handed way that Moscow responded.

In the West, Ukraine and Moldova are no longer interested in any cooperation with Moscow, Panfilov says, and Belarus, the only route Moscow has to Europe, is turning away from Russia as Alyaksandr Lukashenka’s statements and his pulling out the chair from under Putin at Minsk showed.

As a result, the year ahead “will become the end of all Putin’s hopes for the restoration of ‘the greatness of Russia.’ The era of the existence of the CIS, which existed for 23 years” despite its inability to achieve anything “is concluding as well.” It and other “integration” projects have done little but provide employment for thousands for Russian bureaucrats.

According to Panfilov, “the process of disintegration is in train,” and ever more people on what used to be called the former Soviet space now “understand” that they cannot depend on Russia for anything they want and that they must live “independently.” Moreover, they understand that Lukashenka has ceded his title of “’the last dictator of Europe’ to Putin.

Unfortunately, Panfilov does not address one part of this equation: the continuing proclivity of governments and analysts in the West to treat the former Soviet space as a single entity, to view these countries through a Russian optic alone, and to the Russian language as the only one they need in any of these countries.

One can only hope that 2015 will be the death of that pattern as well.