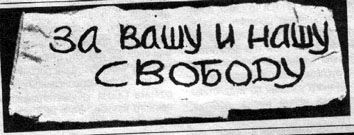

Today, I got a unique opportunity to talk with Pavel Mikhailovich Litvinov, one of the Seven who came out on the Red Square in Moscow in 1968 with the famous motto: "for our freedom and yours." Earlier, I met Pavel Mikhailovich at a rally outside the Russian consulate in New York, but I did not know who he is at the time. Later he left a comment with words of support under one of the photos from our protests. For me and like-minded people, these Seven have always been a prime example of honor, conscience, and nobleness. I cannot explain what I felt when I realized what a person showed us his support.

Q: Pavel Mikhailovich, protests have become a regular occurrence in today's Russia; however, the numbers of participants are very modest. Many of those who are unsatisfied with the state of affairs in the country and the actions of the governments do not come out to protest, as they believe that it will not change anything. Others are simply scared of repercussions. In 1968 the situation was even more difficult, and I am sure that you understood that it's unlikely that your protest will affect the events in Czechoslovakia. More importantly, you surely realized what kind of scary repercussions awaited you. But you still came out. What moved you?

A: First of all, I will say that I had the feeling that it is impossible not to come out. It was my duty as a Soviet citizen, and I had the feeling of responsibility for what our government was doing. They occupied a sovereign country, Czechoslovakia, sent their troops there, and said that this is all done in the name of all Soviet people. I wanted to say that maybe all Soviet people, but not me. It was psychologically much easier to come out than not, and when I made the decision, I felt enormously relieved, as if I was flying. Naturally, we knew that we would be incarcerated, and we were expecting much worse than what happened. I was given a maximal exile, yet only an exile; others received labor camps, but Viktor Fainberg and Natalia Gorbanevskaya had it the worst: they were locked up in a psychiatric hospital, after being accused of acting out of madness. The feeling that this will change nothing was there, of course, but on the other hand, the mere fact that we were locked up and beaten indicates that this was very important. They wouldn't lock us up if they didn't care. As they say today: "oh it's a minority, it's a small number of foreign agents." But for some reason, these "agents" are locked up. It's absolutely clear that they are most petrified of light. As I wrote recently, they are like cockroaches, who act in darkness, but as soon as the light is switched on, they immediately freeze. The most important things out there are free discussion, free protest, and independent thinking. This is what worries them the most. This is why Ukraine worries them. Of course, there are economic reasons, they want to control a territory, but most importantly, they understand - and Putin understands - that if Ukraine achieves its free European future, Russia will look very pathetic next to her. This scares them the most. Because they always say: "oh some kind of Ukraine, the little sister, distorting our language," and suddenly they have become free, while we are still living in shit.

Q: I saw on your Facebook a photo with Mustafa Dzhemilev (tr: the leader of the Crimean Tatar community). Are you friends with him?

A: "Yes, he and I are close friends since 1967. We met in a Moscow suburb through mutual friends, Crimean Tatars, and have been friends since. We wouldn't see each other for many years: sometimes he would be serving a sentence, sometimes I would, then I emigrated. But every time there was an opportunity, we would see each other. For almost 20 years I wasn't allowed back in Moscow, I lived in America, and as soon as they let me go back, Mustafa flew in from Crimea. Crimea was still Soviet, a part of the Ukrainian USSR. Then we saw each other on many occasions in America. For many years, I vocally advocated for Crimean Tatars. It is an amazing nation, I love them very much, - and the fact that they started peaceful resistance on a national level, they wrote polite letters to the Central Committee and to Brezhnev, wrote them stubbornly, - of course we admired that. Indeed, they had become a part of our resistance movement, the one that people later started calling the dissident movement. There were a few people who started to be friends with Crimean Tatars early on, and with Mustafa. Mustafa had a vivid personality, and we loved him and love him very much. An interesting question came up when I first saw him after a long break in Moscow in 1990. It was just my earnest question: would your people prefer to be with Russia or Ukraine? The Soviet Union had not fallen yet at the time, and it was not clear what was going to happen. And he said: "there is no question: with Ukraine". This doesn't mean that he was always happy with Ukraine, but there was no question for him from the very start."

Q: How do you assess the events in Crimea? I mean the so-called 'referendum' that happened in March, and its consequences.

A: The 'referendum' is fiction, it's a crime, it's a violation of international law, it's an invasion of a sovereign country. It is possible that there could be some discussion about the status of Crimea, and many people who live there would probably vote for joining Russia. Many countries had problems like that, as we saw recently in Scotland, in Spain with other ethnicities. In many places there are problems like this, and they need to be discussed, and Ukraine needs to be more sensitive towards Russians. They made a big mistake, the language law that they wanted to repeal. But what Russia did - secretly introducing troops, essentially occupying Ukrainian territory - that's lawless. Then they tried to do the same with Donbas, but received resistance, started a war and already killed thousands of people. This is criminal behavior, there can't even be another opinion about this. Any conscious person would call this aggression, occupation of a foreign territory, annexation, anschluss.

Q: The Ukrainian pilot Nadiya Savchenko is currently imprisoned in Russia. She announced a hunger strike that has been going on for 52 days already. What do you think we can do to help her?

A: I personally already signed a few letters in her support. This is an additional crime. There is a war, there are prisoners of war who need to be treated like captives, rather than criminals. The fictitious court case about how she supposedly coordinated the killings of civilians is absurd. It's absolutely clear that she was captured for intimidation and out of some political motives, but she turned out to be a strong and respectable woman. I'm very scared for her life. The question needs to be raised, because the entire war is terrible, but the life of this woman deserves a special approach.

Q: You know about the cultural figures who signed the letter of approval of Putin's politics. Right now, people in many cities protest against the so-called 'signatories'. What do you think, are these protests justified, or should art and politics be separate?

A: "This is a very good question. I believe that in general, politics and art should be separate, and if people just came to perform, it doesn't matter which country they are from. They have the right to perform, art knows no borders. There were such cases in the Soviet times, when almost nobody was allowed to leave, and to leave for a tour was a miracle. There were outstanding poets, such as Okudzhava, Vysotsky, actor Andrey Mironov, who would be allowed to go perform in America sometimes. And there were Russian emigrants who started a campaign against them. I was very actively against this campaign, because these were oppressed Soviet people who were allowed to leave so they could show the World that there is independent art in Russia (although it was not entirely independent). But these people had never actively expressed their support for the vile politics of the Soviet government.

What disgusts me now is that people like Gergiev, Netrebko, many writers and movie directors signed a letter in support of Putin's occupation and attack on Ukraine. This is disgusting, and of course it is necessary to publicly denounce them. I am very happy that the group in which you participate has been tactically, politely, but obstinately informing people, Americans and Russian immigrants who go to these concerts, about this issue. This is extremely important! These people have identified themselves with the politics of war crimes. One specific case is the famous movie director Pavel Lungin. I know him very well, he is younger than I, my parents were friends with his parents. They were wonderful people. They passed away, and I am somewhat glad that they don't know that their son signed this letter. This simply gives me a heartache. While his parents weren't members of the dissident movement, they were sympathetic, they helped financially, they distributed Samizdat. And Pavlik grew up in this house! This is vile, and I am very repulsed by the fact that major actors, the most famous people endorsed the crimes of a practically fascist level."

[hr]Featured image: Pavel Litvinov, Viktor Fainberg, and Mustafa Dzhemilev, who protested the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, 47 years later