Some say her work is akin to tilting windmills -- no lawyer can ensure justice in Russia's political trials. She says publicity is essential so the political prisoners are not tortured. One thing is sure: she has become a serious pain in the neck for the occupation authorities.

“I only feel fear in one instance – when people get arrested.

This is what brings tears to my eyes. Not only the arrest itself but probably also my powerlessness and because it is hardly possible to provide help in this country [Russia].

Because we all know perfectly well: however competently, correctly, and meticulously one approaches a particular case – if it has an orderer, there certainly will be an indictment,”

says Lilia Hemedzhy, a Crimean Tatar lawyer who has since 2014 tirelessly defended her compatriots subjected to political persecution by the Russian Federation.

Her motivation is simple:

“I want to help my people and all people living in Crimea. So that they are free from persecution, free in movement, entrepreneurship, and expression.”

With her head up, set back shoulders, and reproving voice she keeps taking on the Kremlin’s system of repressions. “Young man, don’t leave, please, why are you so shy,” Lilia wisecracks at one of the policemen who is leaving after groundless interference in one of the meetings of Crimean Solidarity in Sudak town.

There, the OMON police and investigators with dogs broke in without warning.

She tries to write down the policemen badge numbers as they randomly start asking for the identity documents of the attendees.

Being a lawyer in occupied Crimea

Being a lawyer in the Russia-occupied peninsula, like any other Russian-controlled territory, means you could get arrested on your way from home to the office. This happened to Lilia’s colleague Emil Kurbedinov on 6 December 2018. He reposted a Facebook post the authorities took issue with.

It also means getting your office window broken by unknowns, or the police delivering warnings that even single pickets are prohibited.

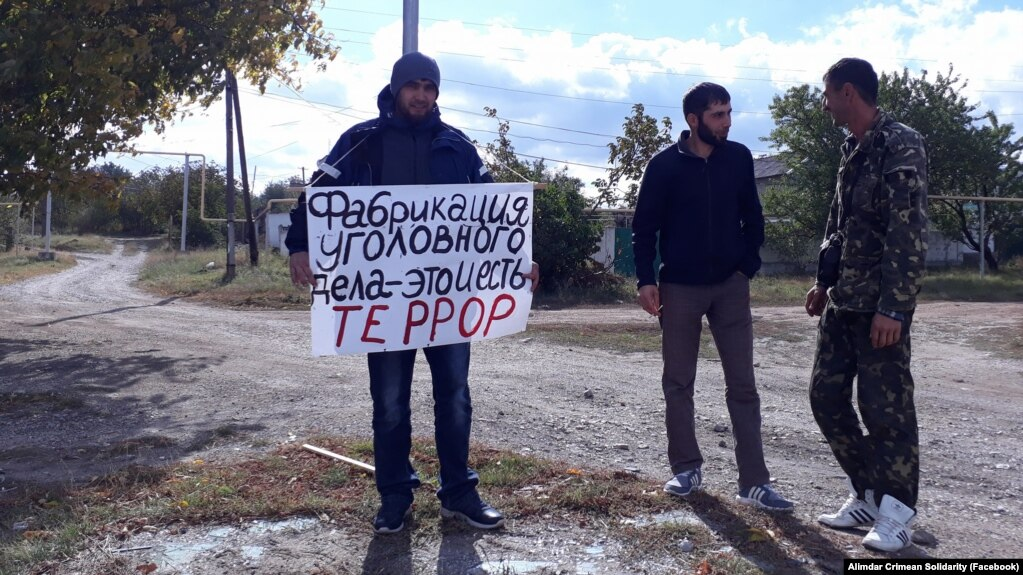

Once, Lilia, Emil Kurbedinov, and their colleagues lawyer Edem Semedlyayev and Crimea Solidarity coordinator Dilyaver Memetov received these warnings even though they had no plans to hold such pickets. The warnings were an act of intimidation because they represented in court and consulted 76 activists who in October 2017 stood in the streets with posters saying “Crimean Tatars are not terrorists.”

“But since when has legal advice become illegal on the territory of the Russian Federation?” fumes Liliia.

In some cases, defending human rights in Russian-occupied Crimea means going to jail. Like it happened to Server Mustafayev, a Crimean human rights defender, accused of terrorism he never committed. Now he faces up to 20 years behind bars.

Pressure from the security officers intimidates everyone but Crimeans, Lilia says, claiming that Putin’s repressive measures backfire:

“It is impossible to frighten people by cranking up the repressive machine – you will only awaken the feelings of those who have until now been keeping low.”

She recalled that Server Mustafayev has dozens of followers, human rights champions. So does Nariman Memedeminov, a citizen journalist accused of extremism.

Pain in the neck

It is no wonder Russian authorities in Crimea have viewed Hemedzhy as a pain in the neck.

Her strength is in uniting people. When in 2017, the 76 protesters who held solitary pickets with signs “Crimean Tatars are not terrorists” were held administratively liable, Liliya wanted to make sure each of them had their own lawyer.

She managed to pull it off. There were not enough Crimean lawyers, so Lilia found 20 people who cared about political repressions yet had no background in jurisprudence. They underwent training and learnt the basics of the process, of how to file writs or respond to a particular accusation.

The outcome was what Hemedzhy called “an absolute victory in Crimean realities": none of the picketers were arrested, all walked away with fines.

Russia’s persecution of lawyers and human rights defenders is nothing new. The approach is the same, only the methods are different. While in 1920-1940 Moscow saw executions of 200 lawyers, with the same number jailed, today the tools used to gag advocates are constrained by international law. Thus, they are more sophisticated -- yet no less destructive.

Trumped-up criminal or administrative cases against lawyers, human rights defenders, and journalists in occupied Crimea leads to many families fleeing their homeland. This has been termed hybrid deportation, echoing Stalin’s deportation of the entire Crimean Tatar population in 1944. But some, like Lilia Hemedzhy, stay to continue peaceful resistance at the risk of their peaceful nights and sometimes liberty.

Lilia took on the profession of a criminal lawyer after Russia occupied Crimea and her compatriots, Crimean Tatars (ethnic Muslim and indigenous people of Crimea) came in the crosshairs of Putin’s repressions. She had never dealt with criminal cases before. And hunger for new knowledge is what helped her succeed in the new realm.

Publicity constrains the torture of prisoners

She says it was not difficult to acquire new expertise. But it is difficult to go to prisons, see ruined lives, and not be able to help. As in Russia, the government, not justice, dictates the verdict.

This brings up the question Lilia is most often asked by her clients, their relatives, and journalists -- what is the point?

She explains that first of all, thanks to her work, the system will not get easy prey.

Second, "Iron" Lilia believes that her and her colleagues' work changes the status quo. The whole world knows about the Crimean cases, the hearings are monitored, and resolutions containing names of her defendants are adopted. Publicity constrains the torture of prisoners.

Before building her line of defence, Lilia asks her clients if they deem themselves guilty and if they would take the plea deal and perjure other Crimean Tatars. She is proud that her defendants

“want to change the world for the better and have no qualms about getting several extra years [of prison] in exchange for not slandering the innocent in this plea deal.”

Imprisoned for discussing love for the Almighty in a mosque

The “political” charges brought against Crimean Tatars fall into several categories:

- the attempt to seize power or overthrow the constitutional order;

- espionage, sabotage, and terrorism;

- or affiliation with Hizb-ut Tahrir.

The charges are made up since no weapons, grenades, or plans to commit terrorism are ever found.

Lilia recalls the cases of Server Mustafayev when he was imprisoned for discussing love for the Almighty in a mosque, Amet Suleymanov who got arrested for talking about the end of life, Eskender Abdulganiyev -- for participating in a conversation on the upbringing of children.

“Attendance at these meetings turned out to be criminally punishable. Experts opine these are the meetings of Hizb ut-Tahrir members.”

The expertise goes like this: “the fact that the word “Hizb ut-Tahrir” is not mentioned in lectures testifies that they [members of the organization] conspire.”

- the Russian government needs to have an internal enemy;

- through the fraudulent charges, it intimidates the population of Crimea justifies the government's actions;

- security officers get easy bonuses for arresting peaceful citizens.

Through these criminal cases against Crimean Tatars, the Kremlin persecutes them on religious and national grounds, Lilia asserts. That is why she files applications to the European Court of Human Rights and the United Nations Committee on Human Rights and engages independent monitors in the judicial process.

Not so long ago, in part, thanks to her efforts, the Clooney Foundation for Justice issued the extensive report “The Russian Federation against Server Mustafayev and others” on the breaches of international law committed by Russia in trying Crimean Tatars.

Born in Uzbekistan, Lilia moved to Crimea, the land of her ancestors, at the age of 12. Her family, along with hundreds of thousands of Crimean Tatar families, were deported to Central Asia in 1944 on the order of Joseph Stalin.

When in 1989 Lilia could finally return home, she was met with discrimination from the local Russians who moved into Crimea after the ethnic cleansing. She shares her childhood memories:

“The first [memory] comes from the school years, when every morning, a school bus would come to pick us up for classes. Local kids, not the Crimean Tatars, would not allow us to sit and I rode standing all the way from home to school, 5 kilometres (3 miles).

And the second is the memory from the academy. There were eight of us, Crimean Tatars, studying in the class, six of whom graduated with honours. When a commission from Odesa arrived for the evaluation of our final thesis, they said in a casual chat following an official part, 'We were shocked to see such a high level of training.' For them, we were sort of shepherds who came down if not from the mountains then from the Dzhankoi steppe.”

Time passes, the cultural bigotry stands still. Years later, a Russian teacher displays a woman wearing a headscarf to explain to Lilia’s kids what a terrorist looks like. “For me, this is unacceptable,” the lawyer says.

For some, Lilia’s work might seem like tilting at windmills but for Lilia’s defendants, like Amet Suleymanov, it means a chance to stay under home arrest due to medical reasons. Often, Russian courts turn a blind eye to the health conditions of Crimean Tatars when choosing a restraint measure.

As a result, gravely sick prisoners have to suffer without treatment in dire prison conditions.

Related:

- Pull off a kangaroo court in five easy steps: a how-to guide from Russia

- (No) right to a fair trial, or a manual to Russia’s conveyor of repressions in Crimea

- “After they electrocuted me, I told them everything they needed.” How Russia’s FSB extracted a “confession” from a Crimean Tatar

- Painkillers instead of hospital: Russia’s torture of critically-ill Crimean Tatar political prisoners continues unabated

- How Crimean Tatar leader Dzhelyal swelled the ranks of Ukrainian “saboteurs”

- Jailing innocent Crimean Tatars to insanely huge terms: a how-to guide from Russia

- Russia tried to break the Crimean Tatars. Their non-violent resistance only grew stronger.

- Torture and imprisonment is the price of freedom of speech in Russia-occupied Crimea

- Seven years of occupation of Crimea: human rights activists systematise human rights violations on peninsula

- “I do not want my children to live in a country of terror.” Four inspiring letters from Crimean Tatar political prisoners not broken by Russia

- Russia’s vile attempts to discredit the Crimean Tatars must not be kept silent

- Pull off a kangaroo court in five easy steps: a how-to guide from Russia

- Photo project spotlights Crimean Tatar kids born after their fathers’ unlawful arrests by Russian occupation authorities

- Russian prison system is a ticking time bomb for health of a Crimean Tatar