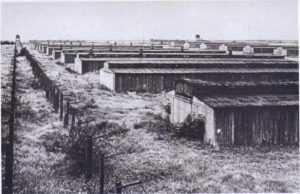

With such words of devotion, freedom, and spirituality Fr. Omelian Kovch died on March 25, 1944, three months before the liberation of Majdanek concentration camp (July 23, 1944). Some 80,000 people were killed in the camp over 34 months including 59,000 Jews. For many prisoners, Fr. Omelian Kovch was their pastor. Today, he bears the title “Pastor of Majdanek”.

On January 9, 1999, the Jewish Council of Ukraine proclaimed Omelian Kovch a “Righteous of Ukraine”. Until his beatification by Pope John Paul II in Lviv on June 27, 2001, Fr. Omelian Kovch was virtually unknown, but today his example gives priests, the faithful, and all persons of good will much to think about.

On April 24, 2009, the Synod of Bishop of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church solemnly proclaimed Omelian Kovch the “Patron of Priests” of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church.

Early years of pastoral service

To understand Omelian Kovch’s faith and dedication, it is necessary to provide the historical and cultural context of those violent, stormy years… when Western Ukraine was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Europe was going through belated death throes of empires and the rise of Nazi Germany, bringing sweeping changes to the political and mental world of the past.

It was during these turbulent times that Omelyan Kovch lived and died, when the plague of Nazism, communism, and chauvinism was raging throughout Europe. Dedicated to the service of God, he fought for freedom and human rights, teaching Ukrainians to preserve and defend their identity, preaching respect and love for others, regardless of nationality or religion.

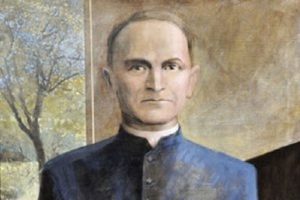

Omelian Kovch was born in a simple peasant family on August 20, 1884 in the picturesque southern Galician village of Kosmach, near the town of Kosiv, in the Carpathian Mountains. There were many priests in the family. His father was a parish priest, and his mother was the daughter of a parish priest. Omelian had one brother and three sisters, all of whom became wives of priests. Eventually two of Omelian’s sons, Serhiy and Myron, would also become priests.

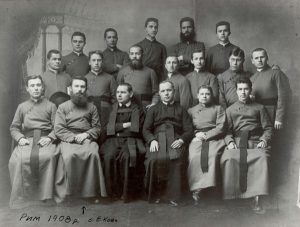

After completing gymnasium studies in Lviv, Omelian Kovch followed his calling and embarked on the road to priesthood. He spent six years in Rome as a seminarian in the Greek Catholic College of Saints Sergius and Bacchus and as student of the Universita Urbaniana of the Congregation for the Propagation of Faith.

In 1910, he married Mariya Anna Dobrianska, with whom he had six children. The following year, Omelian Kovch was ordained presbyter by Bishop Hryhoriy Khomyshyn (1867-1945), who was also persecuted and martyred by the Soviet regime. Khomyshyn was a fierce critic of the Soviet system, having called the occupying force “fierce beasts animated by… the devil”. He was arrested in 1945 at age of 78, interrogated and tortured for eight months, and thrown into Lukianivska Prison in Kyiv, where he died on January 17, 1947. He was beatified together with Father Omelian Kovch by John Paul II.

In 1912, young Omelian was assigned his first parish in the town of Kozarac (today’s Bosnia and Herzegovina). His parishioners were poor Ukrainian emigrants, so Father Omelian and his family lived in extremely difficult conditions.

However, turbulent historical events interrupted his quiet pastoral life. In 1914, with the outbreak of World War I, Kovch returned to his beloved Halychyna, which soon became the arena of one of the bloodiest wars in European history.

In 1918, Omelian Kovch joined the Ukrainian Galician Army, acting as field chaplain and spiritual adviser. During the Ukrainian-Polish war of 1918-19, he participated actively in the battle for Lviv and in the Chortkiv offensive. Aware of Kovch’s courage and dedication, his commanding officers allowed the priest to remain on the front lines and support the soldiers.

In fact, during these turbulent years of war, Father Kovch remained steadfast in his faith and patriotic spirit. As a priest, he was not allowed to take up arms, but he was often seen with his soldiers, joking about his priestly mission and service.

“I know that a soldier on the front line feels protected when he sees a doctor and a clergyman alongside… You all know that I’m a saintly man, and a bullet cannot easily find and hit a saint.”

Together with other soldiers of the Ukrainian Galician Army, he was taken prisoner by the Bolsheviks. The prisoners were herded onto wagons and taken to the place of execution. At one of the train stops, a Russian soldier released the priest with the words, “Father, do not forget to pray for me.”

Omelian Kovch was then imprisoned by the Polish authorities and sent to a work camp where he tended the sick and wounded. He was released when the Ukrainian-Polish war ended in July 1919.

Family life and spiritual service in Peremyshliany

In 1922, Omelian Kovch received a parish in Peremyshliany, a small town in Lviv Oblast, which, like most settlements in Western Ukraine in those years, was populated by Ukrainians, Poles, Jews, Gypsies and even a few German families.

Despite the recent war and the complex history of relations between these peoples, most villages lived quite peacefully, tolerant and respectful of the traditions and rites of others. When the Christian community celebrated a major religious holiday, the Jews closed their shops and took a day off, as did Christians on any particular Jewish holiday.

Father Omelian spent the relatively peaceful interwar caring for his parish, helping the poor and needy, participating in community activities, and fighting against “Polonization”. He understood that Ukraine, a stateless nation, was doomed to fight for its rights and freedom, but the main thing was not to submit.

“Do not weep, but build and achieve! The strength and authority of each nation lies in its people’s national and spiritual consciousness,” he said.

Father Omelian founded a Narodny Dim (People’s House where community members could meet and celebrate holidays), a Prosvita reading room, where villagers gathered to read and discuss different matters, a theatre group for young and old, a kindergarten, and even created a Ukrainian Bank, which was aimed at giving the Ukrainian community some financial independence.

Through metaphors and symbols, Father Omelian encouraged his parishioners to stand up for their rights. It was often during his sermons that he spoke out against the Polish authorities and their policy of “Polonization”.

“The master of the house invited some guests to his home, but a few uninvited people also came, and it was difficult to ask them to leave. They sat down at the table, and made themselves at home. One uninvited guests turned and said: “Move over, Ivan!”… and pushed Ivan strongly away. Ivan humbly moved away, further and further until he found himself on the doorstep of his own home.

Ivan! How long will you keep moving away? How long will you, the master of your home, be a slave?

Be strong, stand firmly on your feet! Have the courage to defend your space as master on this Earth! Get rid once and for all of this slave mentality before those who, by force or deceit, impose their rules upon you! You see this place? This is my place; this is where I preach. Everyone, my people and others, the invited and the uninvited, must know that ‘Ivan’ will never leave his place. He, and no other, is master here! ”

The Polish authorities resented Kovch’s public activities and his membership in the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), which they saw as a threat to the integrity of their state. From 1925 to 1934, his home was searched over forty times and he was arrested and imprisoned several times for his “nationalist ideas and activities”. According to the testimony of sister-abbess Olena Viter and the head of the OUN National Executive Bohdan Kordiuk, Father Omelian was an active member of the OUN and headed the propaganda department.

Father Omelian and his wife knew all the poor and needy families in Peremyshliany and the surrounding villages. On every holiday, these families knew that Mariya Anna Kovch would cook up delicious meals for their children, feed them and clothe them. The Kovch family cared especially for orphans, took them into their own home and encouraged parishioners to do the same.

“Angels hover over that house,” said the villagers, pointing to the Kovch home.

Nazi German occupation & the persecution of Jews

On June 22, 1941, the German army marched into Ukraine, beginning a new stage of persecution, savage repression and enslavement in the western regions. The Nazis replaced the bloody Bolsheviks, but they had no intention of restoring either the Polish or the Ukrainian state. Ukraine was to be a colony of the Third Reich, and its population were to work as slaves under the new masters.

In September 1941, documents and witnesses report that a group of German SS soldiers locked the doors of the Peremyshliany synagogue, threw incendiary bombs into the crowd of faithful, and surrounded the building with troops and weapons.

Leopold Kleiman-Kozlowsky, a former resident of Peremyshliany remembers:

“The Roman Catholic priest and a group of people ran to Fr. Kovch and told him the synagogue was in danger. Kovch, who was fluent in German, hurried over to the synagogue and shouted at the German soldiers to let him into the building. The soldiers were struck by his courage and left the area. Fr. Kovch rushed to open the doors and began pulling people from the burning building. Among them was Aharon Rokeach, the rabbi of Belz, who was visiting our town at that time.”

In 1942 the Germans created a ghetto for Jews in Peremyshliany. From there, the Jews were deported to German death camps.

Despite obvious dangers and difficulties, Father Omelian remained faithful to his calling and moral values. He began organizing different strategies for harboring Jews and helping them escape. It is not known exactly how many Jews Fr. Omelian hid in different places or how many he kept alive by organizing the delivery of food and clothing to their hiding places.

According to preserved documents, Father Omelian Kovch baptized over six hundred Jews. It was in this way, by issuing false baptism certificates, that Father Omelian was able to save brother and sister Rubin and Ida Pizem, who managed to escape the Holocaust and later gave testimonies of their escape.

The priest knew this would not end well, but he continued to do serve God and perform his duty.

On December 30, 1942, Father Omelian was summoned to the Gestapo. This was not the first time, but deep down he knew that he would not return home. The Kovch housekeeper Maryna writes:

“Father Omelian got dressed, put the house keys on the table and asked me to tell the children to remain dignified. They were not go to the Gestapo headquarters to plead for his release.”

The Gestapo arrested and transported Fr. Kovch to Lviv where he was held and tortured in the Prison on Lontskoho Street.

His family, friends and even the Metropolitan of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, Andrei Sheptytsky, did their utmost to free him from prison. The Nazis set a single condition: Fr. Kovch must make a written commitment to stop helping Jews. Father Omelian refused.

“Listen to me, Mr. Stavitsky [the SD officer]. You’re a police officer. It’s your duty to search for criminals. Please leave the affairs of God in God’s hands.”

The officer was outraged by the priest’s defiant response, and ordered him returned to prison. The Gestapo continued interrogating and torturing him, but he did not break.

Majdanek concentration camp

In 1943, the Nazi German administration sent Omelian Kovch to Majdanek concentration camp, near Lubin, Poland. He was given a prison uniform and assigned the number 2399. In a letter addressed to his family and Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky Fr. Kovch wrote:

“I understand that you are trying to free me. But I am asking you not to do anything. Yesterday they killed 50 people here. If I were not here, who would help them to endure this suffering and enter the other world? They would leave our world with their sins, in a deep despair that hangs over this hell on earth. But now, they leave with their heads held high; their sins are left behind. They cross the bridge with joy in their hearts, and I see peace and tranquillity in their eyes.”

Omelian Kovch believed that it was here, among those doomed to death, that he would best fulfill his mission. In another letter he writes:

“I thank God for his benevolence to me. Besides Heaven, this is the only place I would want to be.

Here were are all equal: Poles, Jews, Ukrainians, Russians, Latvians, and Estonians. I am the only priest here. I can’t imagine what would happen here without me. Here I see God, Who is the same for everyone, regardless of the many religious distinctions that exist among us. Maybe our Churches are different, but they are ruled by the same all-powerful God.

When I celebrate Holy Mass, everyone gathers to pray… They pray in different languages, but doesn’t Our Lord understand all languages? They die in different ways, and I help them cross that bridge.

Isn’t that a blessing? Isn’t this the best crown the Lord could put on my head? It is so. I thank the Lord a thousand times a day for sending me here. I couldn’t ask Him for more.

Do not worry and do not despair about my fate. Instead, rejoice with me. Pray for the souls of those who created this concentration camp and this system. They are the ones who need our prayers… May God have Mercy on them.”

Omelian Kovch, prisoner No.2399, devoted his time to all the prisoners in the camp and, like the other inmates, carried out hard physical labour. He gave spiritual consolation to everyone, regardless of their nationality or religion.

The terrible camp conditions finally broke Father Omelian’s health. He died on March 25, 1944, a few months before the liberation of Majdanek. The official cause of death was heart failure. The body of the Ukrainian priest, like thousands of others, was burned in one of the camp crematoriums.

Omelian Kovch adopted Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky’s policy and implemented it widely during his service in Peremyshliany, namely the development of language, culture, education, and economic initiatives of ordinary Ukrainians. He knew that in order to build an independent, strong, and united Ukraine, Ukrainians must first identify themselves as Ukrainians.

Besides his dedication to the nation, Omelian Kovch was an example of love and sacrifice. At the cost of his own life, he saved hundreds of Jews in Lviv region during the Holocaust.

Afterword

The amazing story of father Omelian Kovch is not very well known, either in Ukraine and in Poland… never mind in the rest of the world. For ten years, historian Volodymyr Birchak has been researching and working on Father Omelian’s biography, which is scheduled for publication some time this year or next year. Hopefully, it will be properly translated and disseminated throughout the world.

On the site of the former Maidanek concentration camp, there is now a memorial museum that commemorates one of the biggest tragedies of human history. There are no personal commemorations in the camp. However, Omelian Kovch is the only prisoner to whom a memorial plaque has been dedicated. It is embedded in a large stone near the main entrance gates and bears these words:

“Here I can see God, the God Who is the same to us all, regardless of our religious differences. Priest Emelian Kovch, Majdanek prisoner No.2399.”

On March 25, 2021, a monument to Ukrainian Greek Catholic priest Omelian Kovch was erected in Lublin, Poland, next to the Majdanek State Museum, founded on the grounds of Majdanek concentration camp.

It was designed by sculptors Oleksandr Diachenko and architect Marta Diachenko. The entire project was initiated and financed by the Committee to honour the memory of His Beatitude the Blessed Omelian Kovch.