The occupation of Eastern Europe in 1944–1945 by the Red Army and the establishment of communist regimes in the region involved means of large-scale repressions, deportations, and the subjugation of the population.

To establish the Soviet-Polish border and resolve territorial disputes, on 9 September 1944 representatives of the Ukrainian SSR and the Polish People's Republic signed an “Agreement on the Evacuation of the Ukrainian Population from Poland and Polish Citizens From the Ukrainian SSR.”

De jure, the agreement foresaw peaceful, voluntary resettlement with the preservation of property, so that Poles could resettle from Ukrainian to Polish territory and vice versa. The agreement could have meaning since the area of what is now Ukrainian and Polish parts of Galicia (western Ukraine and south-eastern Poland) was populated by a mixed Polish-Ukrainian population. This was a source of constant political, cultural, as well as military conflicts between the two nations.

The agreement, using the previously defined Curzon Line, divided Galicia into Polish and Ukrainian sections.

In reality, however, the resettlement was conducted compulsorily. The most tragic consequences were that Polish military units and gangs used the agreement to intensify repressions against Ukrainians and evict them even from exclusively Ukrainian villages, thus making all eastern Polish regions “clean.” In other words, an ethnic cleansing of about 500,000 Ukrainians.

During the 1946-1947 Operation Vistula, the remaining 150,000 Ukrainians in eastern Poland were forcefully deported by the Polish government to the north-west of the country so that they were dispersed and no trace of the Ukrainian populace was left in their native villages.

To this day, these events fuel the main Ukrainian-Polish controversy, hampering current relations between the two countries. While Ukrainians denounce Operation Vistula and the massacre of entire villages in 1944-1946, Poles revile the Volhynia Tragedy, claiming that in 1943-1944 units of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) killed 40,000 Poles in Volyn and eastern Galicia, former territories of Second Polish Republic now in western Ukraine.

Resolution and reconciliation will require both sides to be open to the complexity of factors that led to these tragedies and at the very least commemorate victims of both nations.

This process is now almost completely frozen, interviewees say, recalling 1944 events and explaining current obstacles to commemorate and honor victims.

Hanna’s family was forcibly deported by Soviet troops, while Oleksandr’s family had to flee from mass killings by Polish military units operating around the towns of Holm and Hrubieszov. After living as itinerants in poverty and hardship, both families finally settled in the village of Sokilnyky near Lviv. Hanna and Oleksandr attended the same school and later married. Their strong cultural bonds helped to preserve their shared history of Ukrainians being deported and their villages destroyed.

These interviews speak of the repression and deportation of Ukrainians by the Soviet regime and Polish government 1944-1946, as well as current issues arising from Ukrainian-Polish historical animus.

Hanna Voloshynska (b. Myshkovska): “They ordered us to go to the forest and take food for three days.”

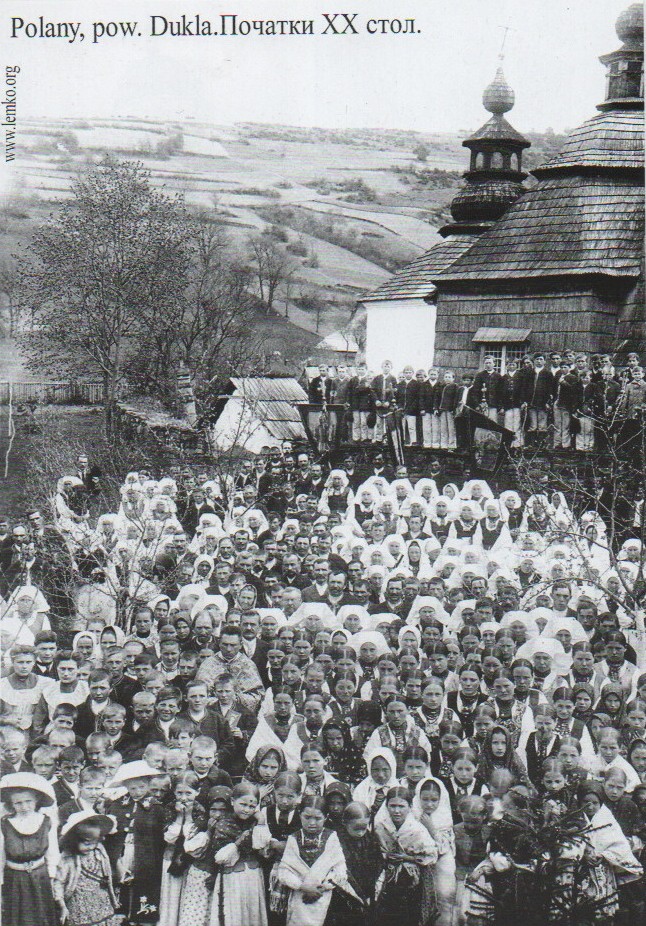

That was in October 1944. I was two-years-old then and remember little, but my mother told me the story of our deportation many times. We lived in the village of Poliany Myscivski in the Dukla area. The village was Ukrainian, but there were also several Polish families. Everyone lived together and there were no conflicts… When deportations started, Russian and Polish soldiers came and ordered us to move out, and that was it. In Poliany they were even more insidious.

By October, Poliany had been on the front line for six weeks, and the battles of the Dukla Pass were ongoing. A lot of our young men died there, because the Soviets just thrust them in front of the advancing army with no way to protect themselves. They were sent forward like cannon fodder and the number killed was hidden.

During these battles, my family and many others were hiding in our cellar, which was quite big, for six weeks. During those weeks, the village was taken away alternately by the Germans and the Russians. Many people died then because of the shooting. My grandfather Fedir Myshkovsky ventured out of the cellar once and never returned. It was very dangerous. I got ill because of the unsanitary conditions.

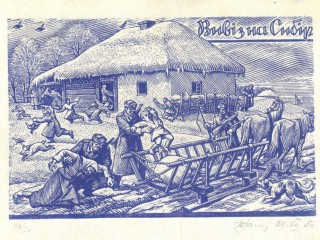

Later that month, an officer and a soldier of the Soviet army came to the cellar and notified us that the next three days battles would be fought. They urged us to flee into the forest and take enough food for three days, pack our carts and round up the livestock. People were not accustomed to deception, they collected everything and followed the soldiers with gratitude. They took us to a safe place and said, “Place your livestock here and your carts there.” People slept in their carts that night.

In the morning, there was no livestock and people realized that it had been a lie. They were distressed and many were crying. Some started running back to the village but Soviet soldiers fired at them, even shooting people in the back.

We were then goaded on to the village of Mshana and then towards the Subcarpathian town of Sanok to the train station where we waited for several weeks for the railway cattle cars in which we were to be deported. Families of local Lemkos [ethnic subgroup of Ukrainians inhabiting the Carpathian Mountains] hosted us temporarily in Sanok, but we were not allowed to return to our homes. We already knew that we had to go east, although no one said where. Our Polish neighbors in Sanok threatened to kill us if we did not leave. Such was the hatred already evident there, although we had once lived together with Poles peacefully.

:

“The village of Poliany near the town of Dukla, as well as other Ukrainian villages of this Lemko region, have been mentioned in historic scripts since the 14th-15th centuries, although these localities may have existed long before that... From 15 October 1944 deportation to the east took place, lasting to 2 August 1946. The following year, from 28 April to 28 July 1947, Operation Vistula continued. The operation was in fact the deportations to the western lands of Poland, with terrible degradation... The extraordinary action of the Roman Catholic priest from Zhmyhorod, Vladislav Findish, who also served in the village of Polyany, should be noted. He issued fictitious metrics to non-Roman Catholics about their baptism in the Roman Catholic Church. This kind of ‘letter’ saved people from the Vistula operation. It is clear that such a practice could not be available to everyone.”

In the winter, we finally departed in the cattle cars. My parents and I were packed into one carriage, and my grandmother in the next. And then at night the carriages were disconnected and rerouted, each in its own direction: this one to Donbas or Kharkiv, and so on. My parents and I were dispatched to the Odesa region, while my grandmother to Ternopil. We only found each other two years later. People were saying that "here and there some from your villages were deported," and so you could sometimes find relatives, even without telephones.

“The locals were friendly, but no one taught us to steal”

Our family arrived in the village of Stanislavchyk in the south of Ukraine, then Odesa and now Mykolayiv Oblast. Our documents were confiscated immediately. They warned us that should we try to escape, we would depart for Siberia. No one had ever seen that Siberia, but everyone knew about it.

So, from early spring 1945, my father worked as a groom and my mother worked in a field brigade. Сollective farms were already established. The locals were friendly, but no one taught us to steal. Nor did they explain that we had to steal to survive the winter.

We just worked until the fall and earned 30 kilos of grain. That’s all. Those 30 kilos of grain were supposed to last for a year. Local people had secret pockets and were able to steal from the collective farm every day to have more at the end of the year. We didn't know that at first.

Moreover, we were people from the Carpathians, used to having a lot of firewood and knew how to bake and cook everything on wood. And here there was no firewood, and it was necessary to learn to bake bread on so-called bricks from cow dung mixed with straw. It was dried in the sun and then stacked like firewood.

Those 30 kilos of grain were the last dive into our despair, and we decided to run away. The locals did not betray our parents. On the contrary, they told us that there were gypsies outside the village and helped us to buy a donkey, a small cart, and even some food.

“Moving for a whole month”

We kept moving for a whole month, at night, secretly, spending days in the thickets. About 1,000 km in all. My brother and I were in a cart, and my mother and father walked. Sometimes we were lucky to find a haystack and could warm up a bit by burrowing into it. But still, I’ve had the scarring from frostbite on my legs since childhood. It was October - November 1945 when the first frosts started. In the end, there was almost no skin left on my mother's feet. She had deep wounds from constantly walking. Moving, moving, moving.

By the end of our drudgery, the children had fallen ill and we stopped near Lviv in the town of Zhovkva, taking refuge with the family of a priest. They had no children and gladly took us in to rest. We were there from October to spring, but we constantly thought about fleeing across the border to our native lands.

My grandfather and grandmother had already tried to run away, as we later discovered. They started their journey two weeks before we arrived. Near the border, they bought hoes and went out into the fields as if they were digging, and in that way they were able to cross the border undetected. Eventually, they got to their village Mystsova in Poland, where grandfather was beloved because he was a church deacon. He had a beautiful voice and was always invited to sing at weddings. But during their first night, the Poles beat him severely.

In 1947, grandfather and grandmother were deported during Operation Vistula -- all those who had stayed in Ukrainian villages of Poland or had somehow made their way back -- were relocated to the north and west of Poland, dispersed to different locations. My grandfather was actually given a large house that was taken from Germans, but he died a year later because of the traumas he had undergone.

The rest of my family tried to cross the border in the spring of 1946, but we were caught by the Soviet police in Lviv. They demanded, "Where are your documents?" We had none and they accused us of being spies.

Dad was arrested, but my mother was able to stay in our cart with my brother and me. My father was gone that night, then another night. My mother was left alone with us and desperate, crying inconsolably. Finally, a gentleman who looked quite wealthy approached us and asked my mother about the situation. He went to the police and must have paid good money to bribe them. When the police returned to our cart, their attitude was completely different. "You know, you better stay here. Here in Sokilnyky is an opportunity to choose a house.” We didn't know how much that gentleman paid them and we didn't even know his name. All her life, my mother prayed for him saying: "God, you know who I'm praying for."

My father returned and we started looking for a house. The best brick houses were already occupied by those who had been deported from Poland a year after our deportation, in 1945. They had been allowed to move in with their belongings and were given the houses of Poles who had been relocated from Sokilnyky to Poland. Only the worst clay houses remained. But my father didn’t pay attention to that, he just looked for a house where at least the windows and doors had not been damaged. When the Poles were leaving, they smashed windows, cut down thresholds and doors so as not to leave anything behind.

"I won't stay here for long, we won't be here,"

said my father when entering a house. However, the borders were already closed and we could not return to our village.

“The first time we went back there, I couldn't refrain from crying.”

In Poliany, we left a huge brick house built in 1937. During the war, a bomb exploded nearby and destroyed one corner. We were only able to return home after the 1991 collapse of the USSR. In 1994, we were able to go to Poland and found our old home. The house was demolished into bricks. Only the basement remained. This was the first time we went back there, and I couldn't refrain from crying. It had been very beautiful. We just sat in our basement, staring and crying. The local Poles saw it all. When we went again two years later, in 1996, we could no longer go to our yard. Locals had fenced everything off. I know we will never go back, but it is very grievous.

There are many healing springs in that area. We had gently rolling mountains covered with forest. We would collect wild mushrooms and berries and dry them. My mother would tell us that when you went into the garden, you could stay in one spot and gather many berries without taking a single step further.

Oleksandr Voloshynskyi: “The largest of these slaughters was on 9-21 March 1944 when the villages of Turkovychi, Sahryn, Mirche, Berestia and others (at least 15) were surrounded and destroyed.”

I can't remember a lot myself, because I was very young, but my older sisters, who were 12-18, studied at the Ukrainian gymnasia (secondary school) in Kholm, and described much about life in interwar Poland and the resettlement of Ukrainians.

I can't remember a lot myself, because I was very young, but my older sisters, who were 12-18, studied at the Ukrainian gymnasia (secondary school) in Kholm, and described much about life in interwar Poland and the resettlement of Ukrainians.

We lived in the village of Poturzhyn, then Hrubieszow, and now in the Tomaszow district. We lived peacefully. There were mostly Ukrainians in our village, but also several Polish families. They usually came to us on our Orthodox holidays, and we went to them on their Catholic holidays. But that did not last long, because by 1938 the persecution of Ukrainians began. Overall, about 150 of our Orthodox churches were destroyed, in particular in the Tomaszow, Hrubieszow and Kholm districts, which suffered the most. My father was the deacon of the Kryliv deanery (group of parishes), he served in a church made of brick which was nonetheless destroyed by the Poles in 1938.

During the German occupation of 1939-1944, a Ukrainian national revival took place. Ukrainian elementary schools and gymnasias were opened in Tomaszow, Kholm, and Hrubieszow. The children all rushed to school, but these freedoms did not last long either. As early as 1942, Poles began attacking Ukrainian families, initially the intellectuals, doctors, teachers, and priests. The so-called cracuses (military gangs) would come, storm a village, smash the windows, and scare the Ukrainians. In 1942-43 there were isolated murders of Ukrainians. Then mass killings began in March 1944.

The largest of these killings was on 9-21 March 1944, when the villages of Turkovychi, Sahryn, Mirche, Brest, and others (at least 15) were surrounded and decimated. The village of Sahryn suffered the most. At least 1,240 Ukrainians were murdered and burned alive on 9-10 March, simply because they were ethnically Ukrainian. In fact, citizens of Poland at that time killed citizens of Poland. This was done by the Peasants' Battalions of Armia Krajova (Polish Insurgent Army).

We go to Sahryn to honor the memory of those who perished. A monument was erected in Sahryn in 2008, but it could not be officially unveiled, as we wanted the presidents of both Ukraine and Poland to be present. This had been the case in other commemorations: Guta Peniatska (where the Polish village in Ukraine was destroyed by the German army in 1944); the cemetery of Orliat in Lviv (the burial place of Polish soldiers who fought for in Lviv in the Polish-Ukrainian war in 1918); and in Pavlokoma (where 366 Ukrainians were killed in 1945 by Poles because of their Ukrainian nationality).

“What dad brought to the cart, my older sister immediately took back to the house, saying ‘no, this is our land, we will not leave it.’”

And so, the story of our family... When I was born, my mother could not spend a single night in the house, because it was dangerous. She spent nights in the garden, hidden between trees, during the winter of 1943-44. Meanwhile, every night my father and other men would climb the bell tower of the Church of Saints Peter and Paul to make sure the village was not attacked.

When mass attacks started in March and a priest was killed in a nearby village by bandits from the Polish Armia Krajova, my mother said that if we did not escape we would also be killed. My parents decided to run away.

Dad prepared a cart, and started loading provisions. But all that my father brought to the cart, my older sister, already 19, immediately took back to the house, saying, "No, this is our land, we will not leave it." And so we fled without anything to the village of Variash, which is now on the territory of Ukraine. A few days later, my father went back to pick up some supplies, but there was nothing left. The house had been burned and everything stolen.

At first, we thought we would be able to return to our land soon, but we did not. That is why today we visit our villages as cultural societies. We are united under the organization Zakerzonnia (Beyond Border of the Curzon Line). We consist of members from associations of Holmshchyna, Nadsiannia, Lemkivshchyna, Liubachivshchyna and also Boykivshchyna (Ukrainian ethnographic regions in south-eastern Poland from which Ukrainians were deported). We also go to the town of Yavozhno to commemorate those who refused to resettle, and were imprisoned in a concentration camp set up by Polish authorities.

Our societies publish books and collections of eyewitness accounts and investigations. We share offices located in the same building in the center of Lviv.

“A bulldozer removed all the Ukrainian tombstones in the cemetery so that there would be no trace of Ukrainians in that village”

When we first returned to my village of Poturzhyn in 1996, I asked a local Pole where the church was … where the priest's house was. He showed me. I asked, "The cemetery was nearby, wasn’t it?" He took me to the cemetery, and there, just a few days earlier, a bulldozer had removed all the Ukrainian tombstones in the cemetery so that there would be no trace of Ukrainians in that village. I asked him, "How so?" And he answered, “Our people did it. I do not approve, but the Poles did it." It was 1996, and the independence of modern Poland was long established. This was done in many villages.

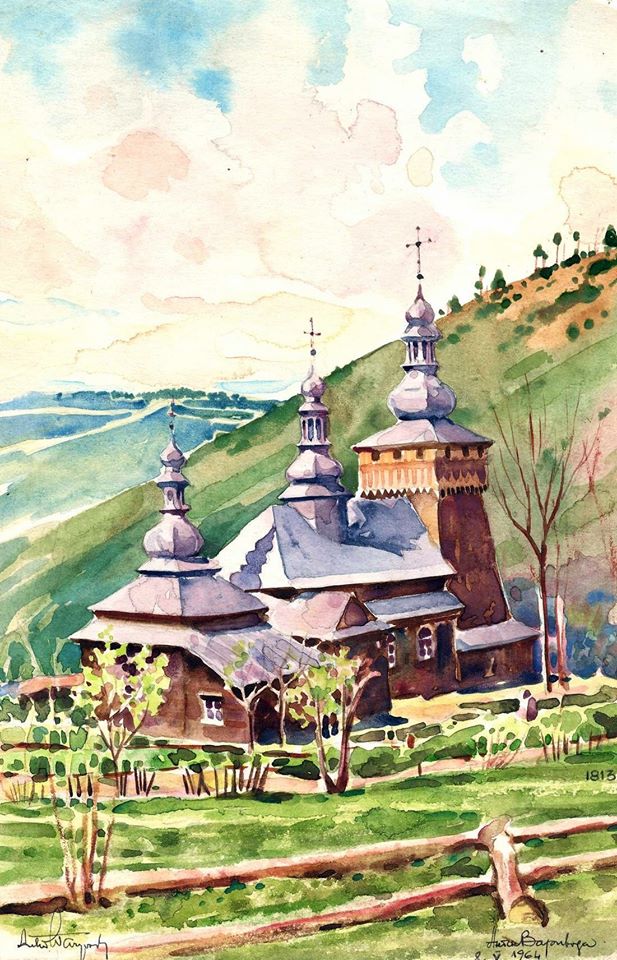

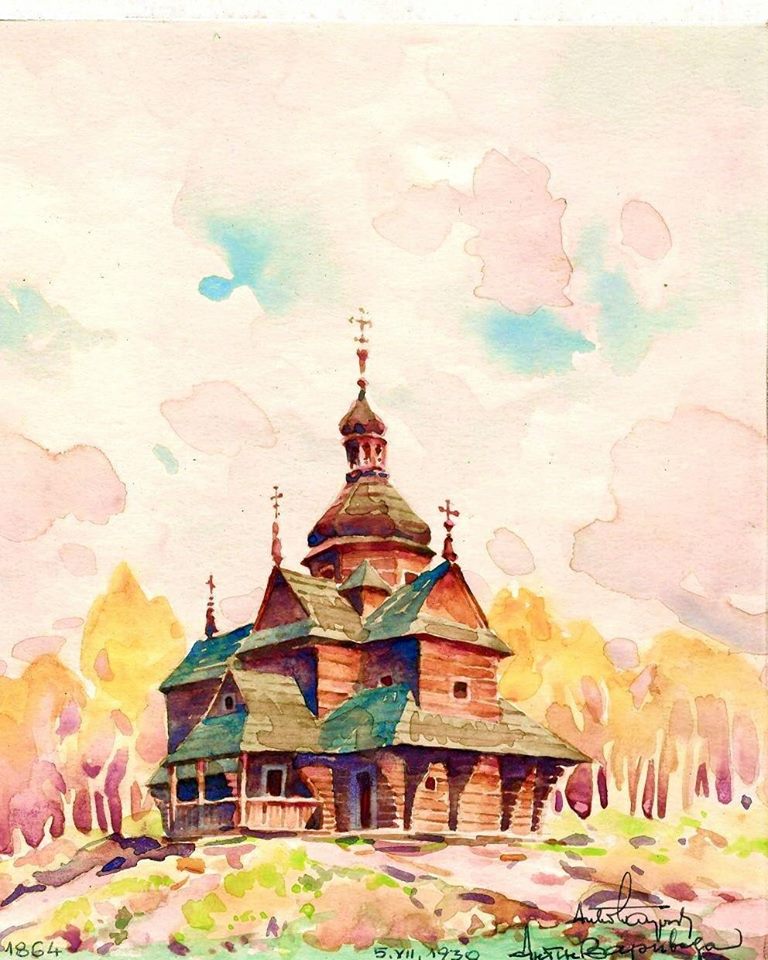

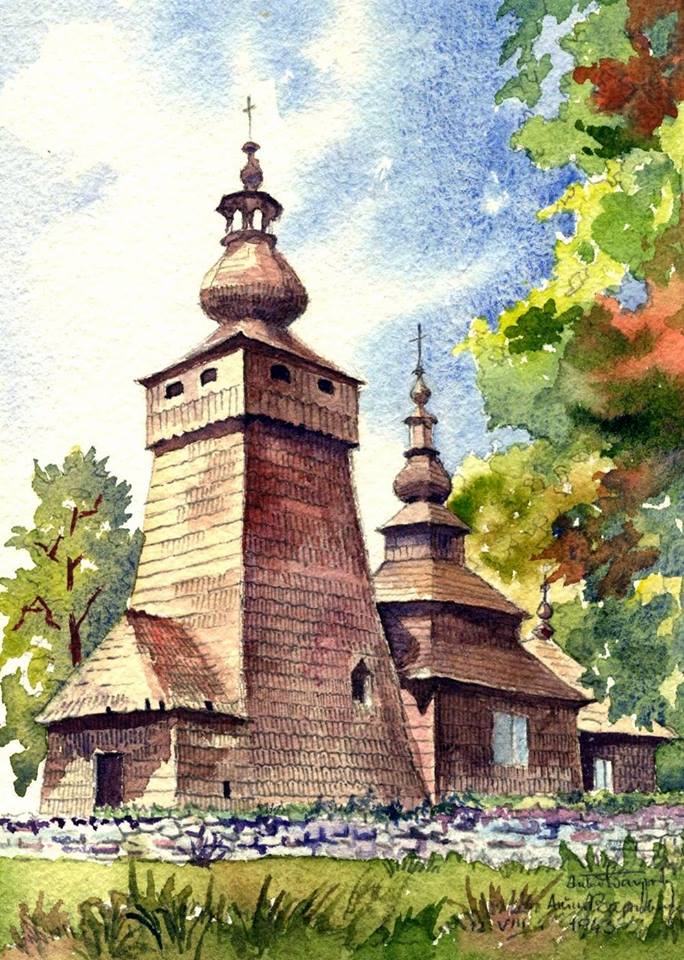

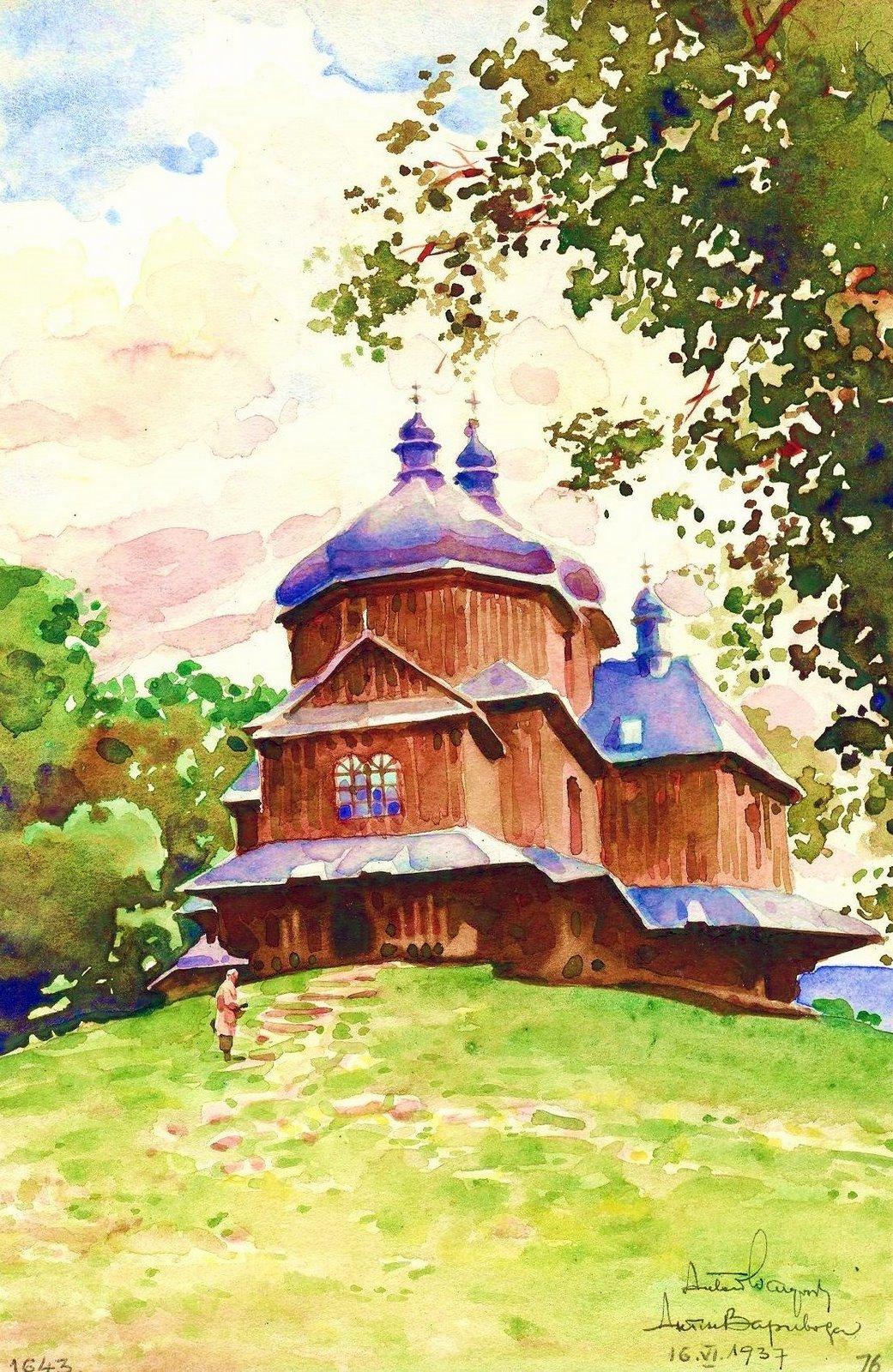

in UNESCO’s World Heritage list. Unfortunately, many of the churches were destroyed during Operation Vistula in 1948. These watercolors depict the destroyed wooden churches of the Carpathian mountains.

Our society traditionally visits Sahryn every year on 10 March, to commemorate the 1,240 people massacred there. We go with the Nadsiannia society to Pavlokoma, where 366 Ukrainians were killed. A memorial was built there, which was unveiled jointly by the Ukrainian and Polish Presidents Viktor Yushchenko and Lech Kaczynski in 2006.

We go to the grave of Mykhailo Verbytsky [composer of the Ukrainian national anthem, who was born in the Ukrainian village of Jawornik Ruski, now in Poland]. We go to Holm to honor the memory of Mykhailo Hrushevsky [eminent historian and the first to author the comprehensive history of Ukraine -- History of Ukraine-Rus, a monumental 10-volume series, generally regarded as a magnum opus and a foundation of the history of Ukraine]. Hrushevsky was a native of Holm.

We visited Holm for the first time in 1994, during a World Congress of Holmshchans, which was held during two days in Lviv, followed by two more days in Holm. We always visit the grave of Pylyp Pylypchuk in Holm, Prime Minister of the Ukrainian People’s Republic (1917-1920). Likely, our King Danylo was also buried in the Church of the Birth of Virgin Mary, in Holm, which has been rebuilt several times. In 1944, the church was appropriated by the Poles and converted into one of their cathedrals.

We also visit the village of Pikulychi, near Holm, and go to the cemetery where soldiers of the Ukrainian Galician Army are buried, as well as official graves of UPA soldiers. Three years ago, during a Ukrainian procession, Polish extremists attacked the participants. Last year the procession was very large -- thousands of people -- and this time there was police protection.

Today, the Polish faction demonstrates little desire for reconciliation. Three years ago, a monument with all the names of UPA soldiers who died at the battle on the Monastyr mountain near Verhrata village was destroyed. Following this event, as well as the desecration of many other monuments, Ukrainians were greatly disillusioned. In response, the Ukrainian government forbade Poles to conduct research in Ukraine.

After the recent meeting of the Polish and Ukrainian presidents, Polish authorities agreed to restore the monument. However, they did so partially. The inscription reads: "In memory of Ukrainian soldiers who fought against the NKVD [the USSR’s People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs — the predecessor to the KGB]." No names or details, which were written before the destruction. The Ukrainian side can't accept this.

Read also:

- The Guardian censors article on Ukrainian historical stamps. Read it here

- Personal memoir: My family in the Polish-Ukrainian borderlands killing zone

- Polish pro-Russian far-right radicals behind arson attempt of Hungarian center in Ukraine

- History of OUN-UPA: the Bandera controversy that eclipsed 200,000 people who fought for the independence of Ukraine

- Information and psychological Russian operations target relations between Poland and Ukraine

- Polish-Ukrainian history: time for a reset

- Poland, Lithuania and Ukraine create Lublin Triangle to counter Russian aggression and expand Europe

- The struggle for Carpatho-Ukraine (1938-1939), or how WWII started for Ukrainians

- Forgotten Ukrainian ornaments brought back to life

- “Rebellious pagan” Ukrainian poet Antonych receives English translation