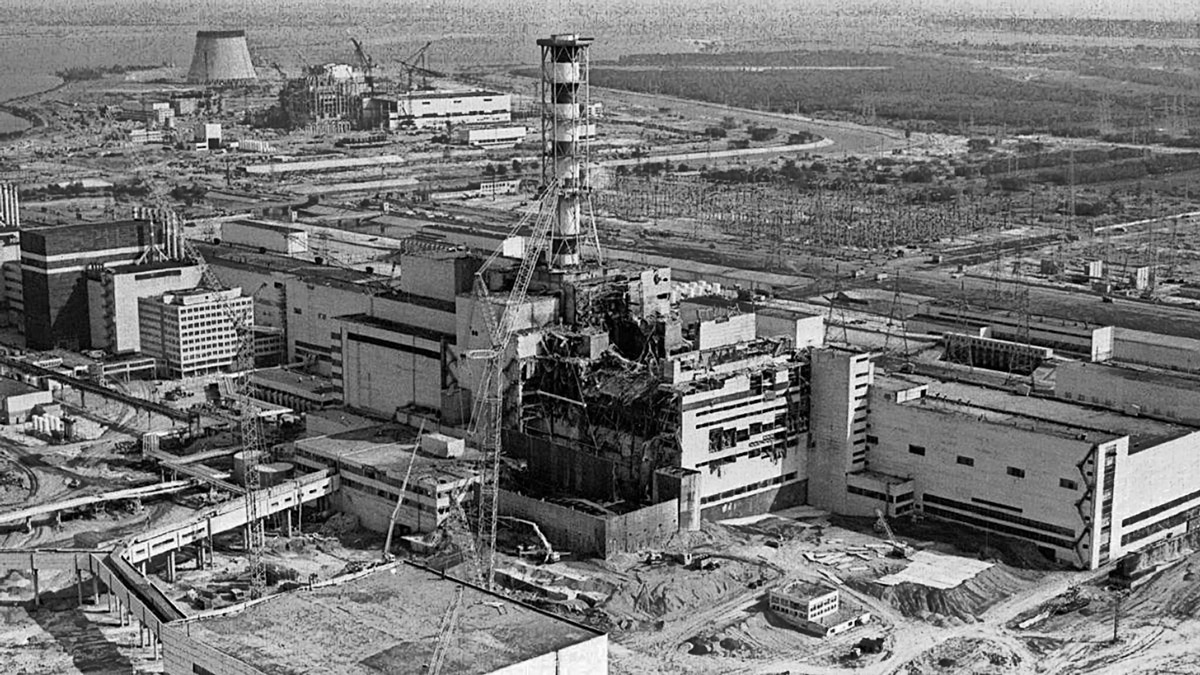

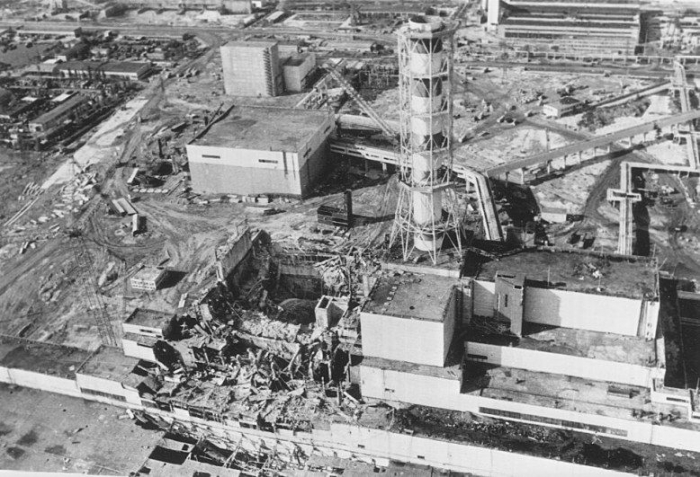

Since the accident at the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Ukraine, 34 years have passed. This accident, the largest ever in a nuclear facility, led to the creation of a 4,700 km² exclusion zone between Ukraine and Belarus. A total of 350,000 people were evacuated from the area.

Initial predictions said that, due to radioactive contamination, the area would be uninhabitable for more than 20,000 years. Chornobyl was thought to become a nuclear wasteland, a desert for life.

Three decades later, studies have shown Chornobyl holds a diverse and abundant animal community. A large number of species that are threatened in Ukraine and in wider Europe reside in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone.

A revealing example of the situation of wildlife in Chornobyl is that of Przewalski’s horses.

The last truly wild horse?

The existence of wild horses in the steppes of Asia has been known in Europe since the 15th century. But it was not until 1881 when the species was formally described to science from a skull and skin collected by Russian colonel Nikolai Przewalski. This is how the horses known as takhi (“holy”) in Mongolia were renamed Przewalski’s horses (Equus ferus przewalski).

For many decades they were considered the last truly wild horse in the world. However, recent studies have indicated they are actually feral forms descended from the first horses domesticated by the Botai people in northern Kazakhstan 5,500 years ago.

In Colonel Przewalski’s time these wild horses were already rare in the steppes of Mongolia and China. Overgrazing and hunting for consumption by human populations caused its final decline. The last wild individual was spotted in the Gobi Desert in 1969.

The situation was not great for the captive population either. In the 1950s, only 12 survived in European zoos. However, they were the foundation for a captive breeding program that has managed to rescue the species from extinction.

Today the world population is around 2,000. Several hundred live in the wild in the steppes of Asia and different areas of Europe. Among them, to the surprise of many, in Chornobyl.

The Chornobyl Horses

At the time of the accident at the nuclear power plant there were no Przewalski horses in Chornobyl. It was not until 1998 when the first 31 arrived in the Exclusion Zone. They were ten males and 18 females from the Askania Nova nature reserve in southern Ukraine, and three males from a local zoo.

After high mortality associated with the process of transfer and release, the high birth rate brought the population to 65 in just five years. The intense poaching between 2004 and 2006 decimated the population. Only 50 survived in 2007.

Intense protection measures have allowed that just 20 years after their arrival in Chornobyl their number has multiplied by five. The most recent census, carried out by local scientists in 2018

, revealed that about 150 individuals live in the Ukrainian part of the Exclusion Zone. Horses are grouped into 13 harem herds with foals, six stallion groups, and some solitary individuals. In 2018 at least 22 foals were born in the Exclusion Zone. Some have moved further north and have already settled in Belarus.

The camera traps installed throughout the Exclusion Zone have revealed that, despite being a species associated with steppes (large unforested areas), in Chornobyl these horses use the forest quite frequently. This includes the famous “red forest”, one of the most radioactive areas on the planet.

Recent fires in Chornobyl have severely affected some of the locations used by horses in the Exclusion Zone. It will now be necessary to evaluate the effect these fires will have on the conservation of the species in the area.

The lessons of the Chornobyl horses

The introduction of Przewalski’s horses to Chornobyl has been a success. Several lessons can be drawn from this success.

The case of Przewalski’s horses reflects that in the absence of humans, the large Chornobyl area has become a refuge for wildlife. This should lead us to reflect on the impact of human presence on natural ecosystems. With no human activity around, even with radioactive contamination, the great fauna seems to thrive.

Other areas affected by radioactive contamination, such as that derived from the accident at the Fukushima-Daiichi plant (Japan), or from the tests of atomic bombs on the Pacific atolls

, also maintain high diversity of wildlife. Perhaps we should reevaluate our predictions for the medium and long-term impact of radioactivity on the environment.

In any case, we need to better understand the mechanisms that allow wildlife to live in areas with radioactive contamination. Many questions remain to be answered. Are organisms living in Chornobyl exposed to less radiation than expected? Does this exposure cause less damage? Do organisms have more effective than expected mechanisms for repairing cellular damage caused by radiation?

To answer these questions, we need more research. In the autumn, we hope to start working with Przewalski’s horses in Chornobyl, trying to unravel the mysteries that allow this species and many others to feel at home in the Exclusion Zone.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.