Clyman wrote no less than 22 articles about the Holodomor in Ukraine and in Kuban, which killed 3.9 million people in Ukraine alone. Her punishment for revealing Stalin’s atrocities to the West was to be expelled from the USSR, being labeled a “Bourgeois Troublemaker.”

Her 1932 articles were published in the Toronto newspaper The Evening Telegram and were found only a few years ago. The initial discovery was made by a research assistant at the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (CIUS), University of Alberta. What followed was a concerted effort headed by Jars Balan, CIUS director, to dig deeper into archival records and find other articles by Clyman. Eventually, the whole story of this brave journalist was uncovered.

Since then, filmmaker Andrew Tkach, whose credits include CBS and CNN, created a documentary about Clyman. He used segments from Soviet films as well as 3D animation of the decades-old photos to make the context of the famine as real as possible. Text from original Rhea’s articles constituted the main commentary in the film.

The documentary draws a parallel to the contemporary war in the Donbas — the Russian aggression that has caused the death of more than 13,000 people, with Ukrainian soldiers perishing almost daily. The film articulates just how much has remained the same since 1932.

Watch the documentary on Vimeo

Who was Rhea Clyman and why did she go to the Soviet Union

“Clyman was initially sympathetic to the revolutionary society Bolsheviks were promising to create, as Stalin embarked on the first Five-Year Plan,” writes Balan in Ukraina Moderna. In 1928, at the young age of 24, Clyman left France by train for Moscow, with little more than £15 ($20) in her pocket.

She set out without making any formal arrangements. She managed to connect with Negley Farson — a correspondent for the Chicago Daily News. It wasn’t long before she was hired by The New York Times Moscow bureau, as an assistant to legendary Walter Duranty.

Clyman undertook to learn Russian, and within a year moved on to the London Daily Express as a Moscow correspondent. Several of her reports were also published in her home city of Toronto, in the Evening Telegram.

In 1932, Clyman set out on her mission. She traveled by rail to Karelia, a region in the far northwestern Russian SSR, and to its capital Kem, a closed city accessible only to Soviet authorities. Her journey then took her over the Arctic Circle to the port city of Murmansk, close to the border with Finland.

Along the way, she visited the northern Soviet labor camps, and experienced firsthand the terrors exacted upon prisoners many of whom were political. She was no longer a naive idealist believing in the goals of the Communist Revolution. Having personally seen the true scale of Soviet repression, she had no doubt about the deceit of the “communist utopia,” which Stalin feigned for foreign correspondents in Moscow.

In the spring of 1932, Clyman convinced two young American women to join her in an 8,000 km road trip. They set out from Moscow to the east Ukrainian city of Kharkiv, then headed down through the Donbas to the Kuban region, in the southwest of Russia, then through the northern Caucasus mountains. Their final destination was the Georgian capital of Tbilisi.

The trip was traumatic, as Clyman and her friends witnessed grotesque starvation in village after village. They followed the route of the so-named “Famine Lands of Russia,” including Ukraine, Kuban and the North Caucasus.

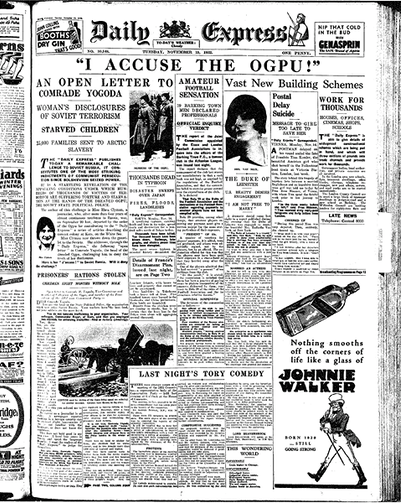

“Children were eating grass, when I saw them a few months ago,” Clyman reported after her expulsion from the Soviet Union. Her article made the front page of the UK’s Daily Express. It was written as “An Open Letter To Comrade Yogoda,” director of the OGPU (Russian secret police).

Unfortunately, the bulk of her eyewitness accounts and her personal photos were confiscated by the OGPU. Nonetheless, many of her earlier articles and testimonials were published, and are available today.

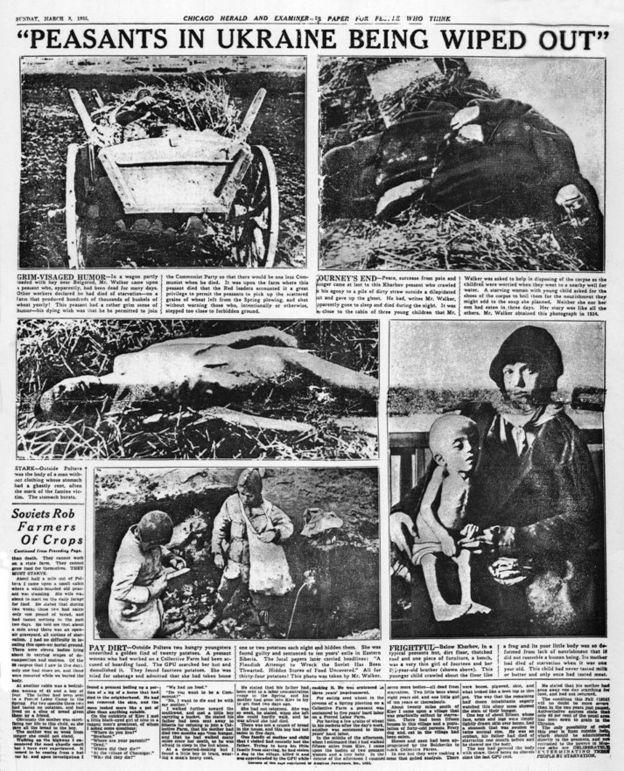

Several of her photos were smuggled across the border by her American traveling companions. They had not been forced to leave the Soviet Union and were able to take the photos out of the country.

Meanwhile, Soviet authorities denounced all of Clyman’s reports as “completely fabricated articles about hunger riots.” However, when other foreign journalists began reporting about the Holodomor, their claims were widely discredited. Among the first reports, in the spring of 1932, the Manchester Guardian carried newswires by Moscow correspondents on the true origins of the famine in Ukraine.

Some foreign journalists made trips -- often clandestine -- outside Moscow to witness the famine themselves. Key among them was the German correspondent of Vossische Zeitung, Wilhelm Stein, who reported on the famine as early as 27 March 1932. Journalists risked their lives to report on the famine, since the Kremlin prohibited foreign journalists to leave Moscow without strict authorization.

A year later, the death toll of the famine reached its worst point. By 1933, the victims were numbering, not by the thousands, but by the millions. The New York Evening Post published the famed article (“Famine grips Russia, millions dying, idle on rise says Briton”) by prominent journalist Gareth Jones (depicted in the 2019 film, Mr. Jones). The article was republished by all prominent newspapers worldwide.

Soon thereafter, witness testimonials began to appear in more newspapers. On 3 March 1936, the Chicago Herald & Examiner published “Peasants in Ukraine Being Wiped Out.”

Clearly, the world was being informed about the famine in the Soviet Union and, particularly, in Ukraine. However, not all journalists recognized Ukraine as a separate nation. Their reporting did not reflect the larger context. Stalin’s ultimate goal was to destroy resistance to the regime -- not only through collectivization, but by subjugating national identity. This was strongest in the populations of Ukraine and Kazakhstan who were most opposed to the Soviets, and thus suffered the worst. The number of deaths in Ukraine alone was close to 4 million, with up to 7 million estimated for the entire Soviet Union.

Read also: Holodomor — Stalin’s punishment for 5,000 peasant revolts

Rhea Clyman is also known for her reporting in Nazi Germany. After her expulsion from the Soviet Union, she made her way to Germany where she again worked as a journalist, reporting on the Third Reich until 1938. With a Jewish heritage, she took a tremendous risk just by living under Hitler’s regime.

“She even survived a plane crash that killed six people. Her life is an amazing series of adventures."

Balan has promoted the story of Clyman’s life through various means. One is by supporting the Holodomor National Awareness Tour, spearheaded by Canadian Ukrainian community leader Bohdan Onyschuk. An innovative project meant to educate school children and the public about the Holodomor, Clyman’s broad range of newspaper reporting is featured. The project consists of a touring bus refitted into a learning center. The bus is, in effect, a mobile mini-museum dedicated to raising awareness in communities across Canada. It includes several displays of original materials from the period, as well as the Tkach documentary film.

How Andrew Tkach made his documentary “Hunger for Truth”

Andrew Tkach’s documentary does not only tell the story of Rhea Clyman. Using extractions by historian Anne Appelbaum, author of The Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine, as well as several other distinguished Ukrainian historians, the film shows key moments of the Ukrainian struggle for independence over more than 100 years.

The creative use of archival photos, original excerpts from films of the 1930s, and a contemporary Ukrainian music score, combine to convey a visceral experience. Depicted are the Ukrainian revolution in 1918; the Holodomor in 1932; Euromaidan in 2014; and the ongoing five-year war in the Donbas.

After this article was published, Andrew Tkach updated "Hunger for Truth" with episodes about the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war. You can watch the film for free on Takflix. The entire film is also available in English on Vimeo. The French version (excluding the segments on contemporary Ukraine) is also available.

In presenting the Canadian premiere of Tkach’s documentary in 2018, Onyshchuk, listed the six most important features of the film:

- The director Andrew Tkach is a documentary filmmaker for CBS and CNN, mainly on the subject of nature. He wanted to make this historical documentary as alive and real as possible.

- The words of Rhea Clyman from her 22 articles drive the story, featuring different stages of her trip.

- Author and historian Anne Appelbaum, one of the commentators in the film, was in the process of writing Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine. She is an expert on contemporary disinformation and Russian aggression.

- All videos used in the documentary are from the 1920s and 1930s and were filmed in the Soviet Union. Fragments from Dzyga Vertov’s (renowned cinematographer) films can be easily recognized.

- SBU archives (retrieved from former Soviet Security Services, KGB, NKVD, OGPU operating in Ukraine) are available for researchers. Testimonies, photos, and comments of Ukrainian historians found in these archives are used in the film.

- Alexey Terehoff, a motion-graphic artist, brought all of the 90-year-old photos to life, As a modern-day art director, he is a wizard in technology. The application of 3D modeling gave the viewer the impression of being physically present in the film — for example, walking down a street.

Read also: “Man with a Movie Camera”: One day of a 1920s Ukrainian city in the early Soviet times

Euromaidan Press has conducted an in-depth interview with Tkach

How did you decide upon this subject?

The film started really because of the first film I did. I did a film called Generation Maidan with Babylon 13. I was in Ukraine just at the end of the Revolution [of Dignity], like a weekend after the big massacres.

Read also: Andrew Tkach’s film “Generation Maidan” and the cinematic propaganda war

Generation Maidan: [embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T4sYAVjq1Lc[/embedyt]

Because of that film, I was contacted by the Canada-Ukraine Foundation, while working in Africa. They sent me Clyman’s articles because nobody really knew about her at that point, and they said: “...well, could you write a proposal for a competition because we have some money from the Canadian government to do a film about her.”

I had a four-day weekend in Kenya and wrote a scenario pretty much based on her writings, and sent it in. Then for six months, I didn’t think about it. And six months later, they called me and said: “That’s your film, you won.”

I still had to finish my job in Kenya, so Babylon 13, our co-producers, started filming the families of Ukrainian soldiers already that winter, and I got there [to Ukraine] only in the spring.

Why did no one know about Rhea Clyman after all her articles from the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany?

We don’t really know exactly. You have to remember that they [articles] were published as frontpage articles at that time, in the 1930s. In the film, you will see the actual copies of those articles. They were not ignored at that time. They were major articles in the major Toronto newspaper. When she was expelled from the Soviet Union, 20-30 newspapers wrote about that.

But you should look at this in the context of time. It was the beginning of World War II. I think a lot of news doesn’t have a permanent kind of impression. For me as a filmmaker, it was interesting that we could bring a person that has been forgotten to life. Of course, that started with the historians who did the initial research.

How did you plan to “bring a person that has been forgotten to life” and how did you succeed?

What is important for me is to frame the topic within the current situation of Ukraine, and of course its relationship with Russian, and, at that time with the Soviet Union. This is not the story that has, in effect, gone away. When Ukraine wants to attain its independence and develop a democratic society it’s like the “empire strikes back.” The attempt by President Putin to restore the Russian World is a parallel to what happened in the 1930s. It was really important for me to put this story in the current context.

The other point is as Anne Appelbaum compared, the 1930s was the age when new media developed. Demagogues became the masters of the radio. It’s just as today when social media has become perfect for the dissemination of disinformation. Having the same facts, people can believe in opposite things. Therefore, we have also interviewed the founders of Inform Napalm, [Ukrainian NGO dedicated to fact-checking, research, and acting as a watchdog on Russian fake news].

How did you obtain the photos for the film?

One of the problems with films about the Holodomor was that people mixed in photos [of lesser famines] from 1921, 1922, 1932, 1946 and 1947. And it was very easy for Soviet apologists to dismiss the accuracy of those films and just the whole subject. So, I thought it was really important to use only the original materials that can be verified. Up to now the only album that people knew about was Grey Album [ an official and proved album with Holodomor photos]. The originals were in the Austrian archives. I contacted them because I needed high-quality photos. But they said: “We don’t own the copyright. If you want to get permission you should go to Samara Pearce. She is the great-granddaughter of the Austrian Engineer who was a prisoner of war from World War I and stayed in the Soviet Union. He was working in Kharkiv and took those photographs of the Holodomor. She was very happy to share them, but told me: “You know, there is another album that nobody really has seen yet.” Now, this is the Red Album, the second album that people before didn’t know existed. There may be even more because Samara said that other materials are in the great-grandmother’s house in England somewhere.

The other photographs that were used were all from SBU (Ukrainian Security Service) archives in Ukraine.

How did you make that fantastic animation for old photos?

[Animation of photos] is not something that nobody has done, but it’s very hard to do it well. It’s just like any art. Basically, you have to break down each photograph into the foreground, middle, and background. And then you have to animate through computer graphics to move through those images to give three-dimensionality. I wasn’t working on documentaries about history before and I was thinking about how can we make this alive. I started looking at techniques. People in Babylon 13 [Ukrainian documentary filmmakers] suggested Alexey, it was basically his work.We did the same with drawings from DNR and LNR prisons. They were drawn by Serhiy Zakharov. Zakharov was arrested and spent 70 days in prison in Donetsk. He is the great graphic designer who created drawings of these prisons and then we used the same 3D techniques to animate them.

How did you decide to use contemporary Ukrainian music for the events related to Holodomor?

Some people like to compose new music for documentaries. But I’ve worked everywhere … in Africa, a lot of America, Asia. I always try to use local sound because it has so much more meaning for residents, especially for Ukrainians of course … all those now-famous Ukrainian artists like Jamala, Onuka, and Dakha Brakha, and Dakh Daughters. We negotiated with all of them and they were able to give us music on discounted rates. We would never have been able to afford all these famous artists. I think it makes a big difference to have artists who are from the culture.

Read also: Explosion of new Ukrainian music after introduction of protectionist language quotas

Will there be a Ukrainian version of the film and what are the plans?

I have already discussed it with Babylon 13. And we will release it online, without any charge. It’s not like there’s any intent of making money on this film. But I wanted to wait to see what happens with any Paris agreements [at the Normandy Four summit on 9 December 2019] ... will there be another prisoner exchange …? Since we have waited this long and the families [of war prisoners interviewed in the film] have waited this long, it would be wonderful to complete the circle. So, I can guarantee that we will release the final version, it’s just the ending that we will change. We can do it as soon as it happens.

How can we combat the Russian propaganda that Holodomor was not genocide and currently Russia is not waging war in the Donbas?

Eventually, the barriers fall. Just as people are slowly starting to understand the campaign to even have a nation-state of Ukraine. When I was growing up, there was no such thing. Ukraine was total fiction. Even just saying Ukraine ... You were basically Russian. There was nothing you could argue about that. I think it’s just a matter of repetition and quiet research. It has an effect.

That effect is a well-deserved tribute to a truly remarkable journalist, whose story is finally in the spotlight after decades of neglect. Rhea Clyman will never be forgotten again.

Read more:

- New version of Hunger for Truth, film about Holodomor& Ukrainian struggle for independence, now online

- “Man with a Movie Camera”: One day of a 1920’s Ukrainian city in the early Soviet times

- UK film director drives to Donbas to film war, spends almost a year there

- New film shows Kazakhs they suffered a Holodomor too, infuriating Moscow

- Holodomor, Genocide & Russia: the great Ukrainian challenge

- So how many Ukrainians died in the Holodomor?

- Was Holodomor a genocide? Examining the arguments

- Holodomor: Stalin’s punishment for 5,000 peasant revolts

- The Holodomor of 1932-33. Why Stalin feared Ukrainians

- Stalin’s management of Red Army proves Holodomor a Soviet genocide against Ukrainian

- Eleven films about Euromaidan you can watch online

- Documentary about Ukrainian mothers of war selected to premiere at Tribeca Film Festival