“Steinmeier’s Formula” has since October 2019 become the number one political controversy in Ukraine. This detailing of the way that the political part of the Minsk Protocol should be implemented has sparked a holy war between those claiming it is harmless and those insisting it will lead to the capitulation of Ukraine’s state interests.

The former say it is merely a part of the Minsk process, seen as the only way to resolve the war in Donbas dragging on between Russian-backed militants and the Ukrainian government for the fifth year. The latter claim that the formula, signed by Ukraine on 1 October, carries the risk of Ukraine going for the Russian scenario of implementing the Minsk Protocol, in which the political regulationй of the conflict takes place before Ukraine physically controls the territory. This is believed to be a gateway to the legitimization of Russia’s puppet political entities in Ukraine’s political system, with Ukraine picking up the bill - and it is protested accordingly.

- Read more: Protests against “Steinmeier’s formula” gather largest crowd since Euromaidan

- Protests against Zelenskyy’s peace plan for Donbas continue as 12,000 march in Kyiv

President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has paid lip service to the “security first, then political regulation” Minsk strategy of ex-President Poroshenko by promising that Ukrainian state interests will not suffer in his peace initiatives, as “red lines” on Donbas will not be crossed.

The main such red line is that local elections in the Russian-backed Luhansk and Donetsk “People’s Republics” (“LNR,” “DNR,” or “LDNR,” also called ORDLO in Ukraine, or “certain areas of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts”) will not take place before Ukraine gains control of the Russian-Ukrainian border, most of which is currently off-limits even for OSCE monitors, allowing for a steady influx of Russian troops and equipment.

Technically, the “formula,” by which a law on the “special status” of the “LNR” and “DNR” comes into force after local elections are held in them, adds little to the Minsk Protocol, although it has other drawbacks, which we have examined in our previous article The real problem with “Steinmeier’s formula” and the Russo-Ukrainian war.

However, the “formula” itself and the controversy surrounding it is insignificant compared with the real problem of the war resolution efforts - the Minsk Protocol itself. Presented by the previous administration of Poroshenko as the only way to resolve the Donbas war (probably because western sanctions against Russia were tied to the implementation of this protocol), if implemented verbatim, it actually will be a ticking time bomb for Ukraine’s statehood. And Russia will agree to nothing less.

Surkov’s secrets have been examined in detail a RUSI report co-authored by the author of this article, "The Surkov Leaks: the inner workings of Russia's hybrid war against Ukraine." They refer to three tranches of correspondence from the office of the top Kremlin aide Surkov were obtained by Ukrainian hackers in 2016-2017. What makes them particularly valuable for discussions about Steinmeier’s formula is the fact that they document what was happening in Surkov’s office when the second Minsk protocol was adopted in 2015 - and the ways that Russia tried to intervene in Ukraine’s political field to secure its Minsk wishes in Ukraine’s Consitution.

Zelenskyy’s idealistic pre-election goal to end the war fast send us back to the birth of the Minsk process in 2014-2015, when Poroshenko, as well, came to power promising to end the war fast. However, this did not happen, and it would be prudent to understand why.

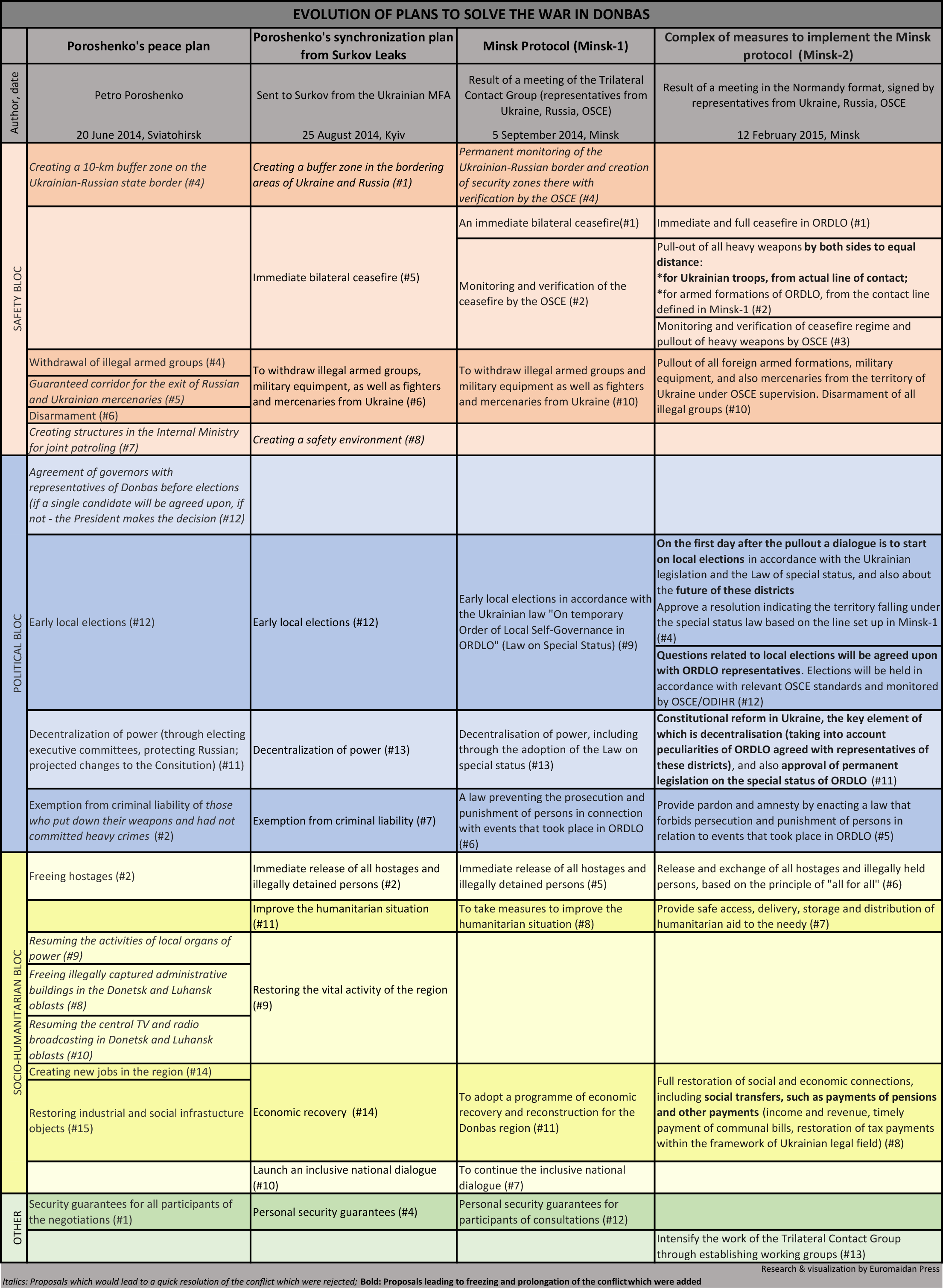

The evolution of the Minsk protocol

The second Minsk protocol is seen today by many as being the only solution for the war in Donbas. It was adopted after an earlier attempt at an agreement, Minsk-1, failed, but is much worse for Ukraine's national sovereignty. If Minsk-2 is implemented verbatim, it will lay out the preconditions for a prolongation of the conflict, not its resolution with the reintegration of the uncontrolled territories into Ukraine.

Because of this, Ukrainian officials both back in the presidency of Petro Poroshenko and currently under Volodymyr Zelenskyy - insist on a Ukrainian version of implementing of the protocol which supposedly doesn’t jettison Ukrainian state interests. This, as it always has been, is met by Russian indignation - Russia insists on a scenario allowing to legitimize its puppet republics in Ukrainian political life, giving Russia endless opportunities to torpedo Ukraine’s sovereignty from within, with Ukraine footing the bill.

From studying the story of how Minsk-2 came about, as well as the emails of Vladislav Surkov, it becomes clear that this is exactly what Russia's goal for the war in Ukraine is, and we should expect no other outcome from the results of the Minsk and Normandy processes.

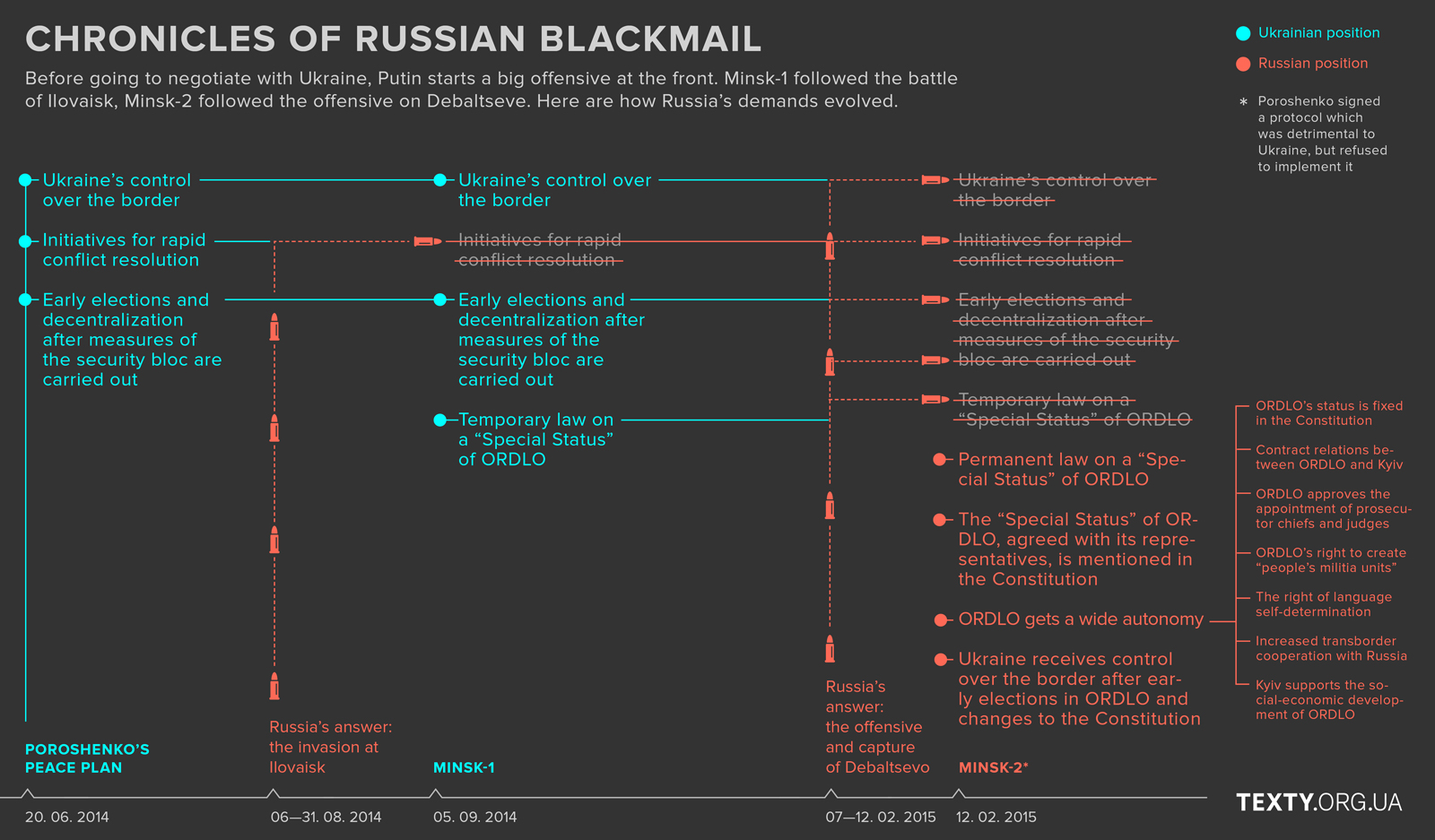

In June 2014, the anti-terrorist operation Ukraine declared against a Russian-backed insurgency in eastern Ukraine was successfully advancing on non-government controlled areas. This changed with the start of Russian cross-border shellings followed by a large-scale invasion, which led to a massive defeat of the Ukrainian army at Ilovaisk, where hundreds of Ukrainian troops were massacred in a "green corridor" despite Russian guarantees of allowing an evacuation.

It was from this position of military defeat that Ukraine entered into the Minsk peace process. On 5 September 2014, representatives of Ukraine, Russia, and the OSCE signed the so-called Minsk protocol (Minsk-1). The document was in many ways a reiteration of a peace plan Ukrainian President Poroshenko made on 20 June 2014.

The proposal contained a number of security steps and urgent measures to restore law and order that never made their way to the Minsk-1 protocol. Among these are such items as the resumption of powers of local authorities, freeing of administrative buildings occupied by Russian-backed militants, resumption of broadcasting of Ukrainian channels into the occupied territories, a guaranteed corridor for the withdrawal of mercenaries.

Among the political steps of Poroshenko’s plan were early local elections, decentralization of power through changes in the Constitution, and amnesty for militants who had not committed heavy war crimes.

The fact that Surkov received a document called “Plan of synchronization of measures to implement the peace plan of the president of Ukraine” from the Ukrainian MFA on 25 August 2014, which largely reiterates Poroshenko's plan, indicates that this course of action was seriously being discussed as an option for conflict resolution, and that Kyiv was still hopeful to reach an agreement with Russia.

The "Plan" details the timeline for the implementation of all of Petro Poroshenko’s plan (sans one clause about the governors). Establishing a buffer zone on the Russian-Ukrainian border was to be finished by 5 September, followed by the freeing of hostages, establishment of OSCE monitoring, bilateral ceasefire, withdrawal of foreign troops and mercenaries from Ukrainian territory (for this, Russia was expected to ensure the self-termination of “LNR” and “DNR” by 14 September 2014, a step which has now been suggested by Leonid Kuchma, causing a fury in the Kremlin). Snap local elections and Constitutional amendments envisioning the decentralization of power were to be adopted by the end of 2014, followed by the economic recovery of Donbas.

But after the invasion of Ukraine and massacre of Ukrainian battalions by the Russian army at Ilovaisk in what was supposed to be a “green corridor” for their escape, timed to coincide with Ukraine’s independence day, Ukraine was in a position of military defeat. Poroshenko was pressed to make rapid steps to stop the bloodshed. It is from this position that Ukraine signed Minsk-1.

It mostly follows Poroshenko’s peace plan. Some steps allowing a rapid resolution of the conflict were jettisoned from Minsk-1 (resuming the activities of local organs of power and broadcasting of Ukrainian TV and radio, freeing illegally captured administrative buildings in the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, joint patrolling of ORDLO territory). One very important one stayed - the permanent monitoring of the Russian-Ukrainian border and the creation of security zones there which would be monitored by the OSCE.

Enter Minsk-2

After Minsk-1, Ukraine swiftly adopted the “Law on Special Status” and a law on amnesty on 16 September 2014. Despite this, the “LDNR” held local elections on 2 November contrary to the democratic procedures outlined in the Ukrainian “Law on Special Status,” and Russia insisted Ukraine must amnesty the separatist leaders of the “LDNR.

The announced ceasefire, although it was never honored fully, managed to cut down military casualties. But by January 2015, the ceasefire had collapsed. Russian-separatist troops won the battle for the Donetsk airport and proceeded with an offensive against the railroad hub of Debaltseve. The increased fighting alarmed France and Germany, and a new deal called “Package of Measures for the Implementation of the Minsk Agreements" was drawn up by French President Macron and German Chancellor Merkel after at a summit in Minsk on 11 February 2015 after 16-hour negotiations with Ukrainian President Poroshenko, Russian President Putin, and the “LDNR” leaders.

According to the study “Russian reflexive control,” the adoption of Minsk-1 and Minsk-2 are prominent examples of Russia’s successful use of reflexive control to achieve its objectives. Here, reflexive control - a Soviet warfare concept in which the adversary is tricked into making self-defeating decisions - is seen as being exercised over Merkel and Hollande. Russia’s armed offensive of January 2015 and Putin’s threat of further escalation of the conflict if his demands were not met hit a trigger point: the European leaders’, and particularly Angela Merkel’s, abhorrence of conventional war, let alone nuclear war, in Europe. Facts of Putin’s “escalation blackmail” regarding Merkel, although not available in the public domain, were confirmed by the personal research of the co-author of the study James Sherr and were never rebuked by German Foreign Ministry representatives.

Other successes of this reflexive control operation include the connection of western sanctions against Russia to Minsk-2, which does not stipulate the return of Donbas but only mentions a “special status,” and the Normandy process, which has unsuccessfully dragged on to this day.

And the political outcome Russia wants becomes clear when studying Surkov's emails related to the Minsk process.

An analysis of the Special Status and Amnesty laws Surkov received on 19 September 2014 from the Center of CIS countries studies headed by Konstantin Zatulin underlines that Poroshenko's "Special Status Law" uses the term “special regime” and said nothing about a “special status.” Moreover, only the territories controlled by the “LDNR” fall under this “special regime,” not the total area of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts as the “LDNR” leaders demand, and the law is temporary - only for three years.

This means, the Center wrote, that Ukraine is not going to recognize the “LDNR” and aims to freeze the situation in Donbas to restore its combat capability and economy, but will not federalize the country, although it may accept “LDNR” (Russian-appointed) leaders into its political field, if the latter will play by the rules.>

Moscow is fine with such a frozen conflict situation, as it allows preserving levers of influence over Ukraine’s foreign policy movements such as NATO accession by unfreezing the conflict and will allow Moscow to continue insisting on Ukraine’s federalization, the Center concluded.

This latter goal of Ukraine’s federalization was voiced by Russian officials at the time of Euromaidan and consistently repeated throughout all the years of the conflict. Moscow’s insistence on Ukraine’s federalization has a clear motive - a less unified Ukraine gives Russia more opportunities to intervene in its affairs and block Ukraine’s rapprochement with the West.

With Minsk-2, Russia moved closer to this goal.

Instead of an OSCE-monitored buffer zone on the Russian-Ukrainian border (step #1 in Minsk-1), the OSCE would monitor both side’s pullout of heavy weapons from the contact line. Local elections were no more seen as the pinnacle of conflict resolution - a dialogue on holding them was to start on the first day after a weapon-free zone was to be established on the contact line between government-controlled territory and the “LDNR,” and Ukraine’s control of the Russian-Ukrainian border would resume only after the elections were already held.

Instead of a program to spur economic recovery once the “LDNR” was reintegrated into Ukraine, Kyiv was to resume social payments to citizens living in “LDNR” - a step which would lessen the financial burden on Russia while allowing the “LDNR” to indefinitely stay as Russian puppet republics.

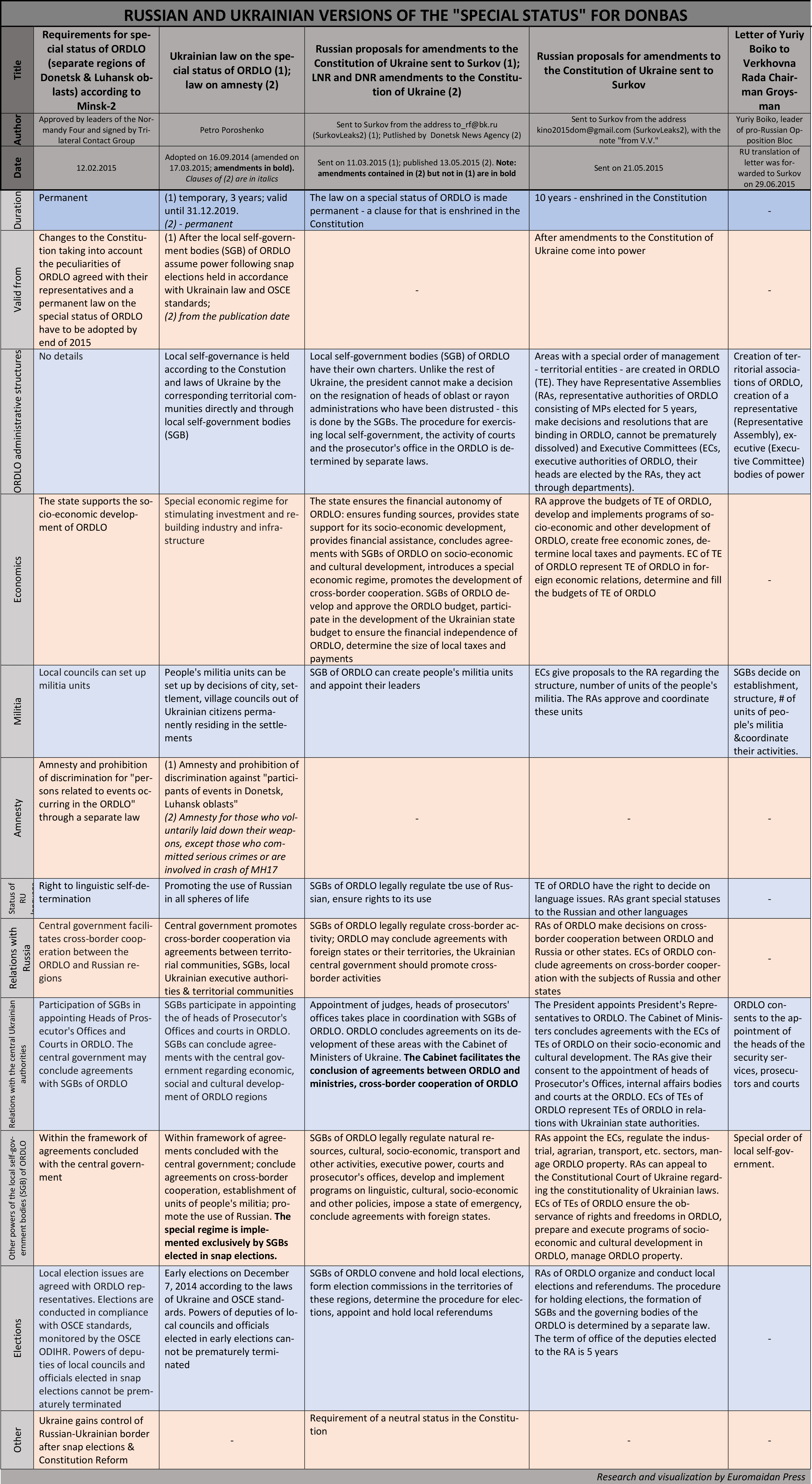

As well, it contained a number of requirements for this legislation (see first column in Table 2): the possibility for local councils to set up people’s militia units, enhanced possibilities for the use of Russian language and cross-border cooperation with Russia, rights of self-government bodies in ORDLO to vet the appointment of Heads of Prosecutor’s Offices and Courts and enter into contract relations with the central government.

Poroshenko’s Special status law adopted in September 2014 already followed most of these provisions of Minsk-2, indicating that these items were already on the table during Minsk-1 negotiations.

But as we have seen above in the analysis Surkov received, Russia’s main interest was in having ORDLO receive a permanent special status. And if the “LDNR” could get a special status, what prevented other Ukrainian regions from demanding the same? Actually, nothing - as the Surkov Leaks revealed, in 2015, the Kremlin coordinated an ambitious campaign to get a Constitutionally-enshrined special status for various Ukrainian regions. It is described in detail in the RUSI report on Surkov Leaks. In parallel, Russia led a game to push through a very special “special status” for its puppet republics.

Russia’s attempts to enshrine Donbas’ “special status” in Ukraine’s Constitution

After the signing of Minsk-2, Moscow started a campaign to enshrine the "special status" of its "people's republics" in Ukraine's Constitution. An email Surkov sent out two days before the Minsk summit, containing a document titled “Referendum (Portnov) 9.02.2015,” suggests that this was the preferred course of legal action for having the "LDNR" receive the status of a Ukrainian autonomous region. (The name of the document suggests it was drafted by the lawyer Andriy Portnov, who is in Ukraine suspected of treason and complicity in Russia’s occupation of Crimea. Having been closely linked to runaway President Viktor Yanukovych, Portnov left Ukraine after the Euromaidan revolution, but after Volodymyr Zelenksyy’s presidential victory, returned and opened 11 criminal proceedings against former President Poroshenko.)

The document by Portnov claims that in Ukraine’s legal system, Ukrainian regions can receive an autonomous status without the need to convene a referendum. All that is needed is to enter changes in a few articles of Ukraine’s Constitution, granting them the status of autonomous entities, and describe the procedure for the formation of their bodies and their powers.

From February 2015 onward, Surkov’s office was focused on changing Ukraine’s Constitution, starting from the mechanism by which Constitutional amendments could made in the first place. Surkov received the first such letteron this issue on 10 February 2015. Just days later, DNR leader Denis Pushilin suggested in the media that the ‘people’s republics’ were ready to suggest changes to Ukraine’s Constitution to the Trilateral Contact Group.

Specific Russian proposals for amendments to Ukraine’s Constitution came through Surkov’s mail on 11 March 2015 and were published by the “LNR” and “DNR” on 13 May 2015 with one minor change (here is an English translation), once again pointing to Russia’s control over the “republics.” Their content is laid out in column 3 of Table 2. In brief, these proposals differ from Poroshenko’s Special status law thus:

- The Special status law gains a permanent status in the Constitution in place of the temporary 3-year period;

- Local self-governing bodies (SGBs) have their own charters, heads of local administrations cannot be dismissed by the president. These SGBs get wide powers;

- Instead of the central government merely a special economic regime for the development of ORDLO, SGBs develop a separate budget for ORDLO and ensure that Kyiv provides enough funds for the “financial autonomy of ORDLO.” As well, the SGBs get rights to legally regulate (i.e. adopt laws on) the use of Russian, cross-border activity, the use of natural resources, cultural, transport and other activities, develop and implement programs, impose a state of emergency, conclude agreements with foreign states or their territories, convene and hold local elections and referendums;

- There is a requirement for a neutral status to be enshrined in Ukraine’s Constitution.

Essentially, the Russian amendments to Ukraine’s Constitution would allow ORDLO to act as a separate state within Ukraine, with the central government footing the bill. Importantly, the requirement of a neutral status would halt Ukraine’s movement towards NATO, which could be seen as another Russian goal for Ukraine.

It is no surprise that these proposals, written in the Kremlin and voiced aloud by the “LNR” and “DNR,” were rejected by Ukraine. What is surprising, however, is that the next Russian attempt scaled the demands up, not down. Surkov received an alternative draft of changes to Ukraine’s Constitution on 21 May 2015 containing proposals from an unnamed individual with the initials “V.V.” They gave the ORDLO even more qualities of a separate state (column 4, Table 2):

- ORDLO territories received a resemblance of their separate parliaments (Representative Assemblies) and governments (Executive Committees);

- The Representative Assemblies were provided the right to approve the budgets of ORDLO, develop and implement all sorts of programs for the territories, as well as regulate virtually all sectors, determine local taxes and payments, grant the Russian language a special status, make decisions on cross-border cooperation. As well, they can appeal to the Constitutional Court of Ukraine on recognizing Ukrainian laws unconstitutional, organize local elections and referendums, approve the budgets for ORDLO, create free economic zones, determine local taxes and payments;

- The Executive Committees got to represent ORDLO in foreign economic relations and in relations with Kyiv, prepare and execute programs of socio-economic development.

So, compared to the previous Kremlin-designed proposals voiced by the “LDNR,” ORDLO would get its own mini-parliament and government.

It is unclear how Russia promoted these ideas within the Ukrainian political process, but a letter of Yuriy Boiko, the leader of the pro-Russian opposition Opposition Bloc party, sent to then-Verkhovna Rada Chairman Volodymyr Groysman implored that these very ideas of the ORDLO getting its own parliament and government were the key to solving the conflict in Donbas (column 5, Table 2).

Surkov was sent a translation of this letter, which is unavailable in the public domain, on 29 June 2015.

All these Russian attempts amounted to nothing.

Poroshenko, after being (apparently) coerced into signing Minsk-2, attempted to make the best of the situation, adopting laws that did their best to spare Ukraine’s sovereignty. The Special status law remained temporary. Although initially, he resisted referring to the special status of Donbas in any way in the required Constitutional amendments on decentralization, he later inserted this brief reference to the law in their transitional provisions:

“The peculiarities of local self-government in particular areas of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts are determined by a separate law."

Reportedly, he made this decision after a meeting with Viktoria Nuland, then-Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs at the United States Department of State. Nuland was also present at the vote for these amendments on 31 August 2015, when mass protests erupted outside the Ukrainian parliament, leading to the death of four guardsmen from the National Guard. The amendments were passed in the first reading; prospects of a second vote for them remained dubious during Poroshenko’s presidency. On 29 August 2019, the project was withdrawn.

Thus, Poroshenko’s bill on Constitutional Amendments contained only a fleeting reference to the Law on Special Status. And the adoption of this law caused great resistance in Ukrainian society, leading to bloody confrontation.

What Russia wants (and without getting which it will not stop the war)

Russia's intentions for the Minsk process become even clearer when one studies the articles written by Russian politologists at, apparently, Surkov’s urging. Starting from July 2015, when it became clear that Russia’s proposals for Ukraine’s Constitution would not be accepted, every one-two months or so, Surkov received lists of politologists to be present at meetings and weekly digests of the articles they wrote in Russian outlets. The articles followed similar narratives, making them a useful source to analyze Russia’s ultimate goal for the Minsk process.

“Only a special status; Donbas doesn’t need Poroshenko’s ‘special self-government regime’” wrote Pavel Dulman on 16 July 2015, slamming Ukraine for “manipulating the text of the Minsk agreements” and citing “DNR” representative Denis Pushilin, who promised to pursue the enshrinement of the “special rights” of Donbas in Ukraine’s Constitution “on the right of equal contractual relations with the Kyiv authorities.”

For Ukrainian patriots, “all Poroshenko did in Minsk is a direct betrayal. And they’re not that far off. Kyiv can’t implement the Minsk agreements, because then it will basically create a confederative Ukraine with an independent Donbas, which recognizes the sovereignty of the powers in Kyiv only formally,” wrote Rostislav Ishchenko on 16 July 2015. It’s clear that the other regions will demand similar rights, he continued. “Implementing the Minsk agreements means destroying the Ukrainian state [...], turning it into a conglomerate of weakly connected autonomous lands…”

Whatever the goal of these statements, addressed to Russian audiences, they do appear to be a rather blunt revelation of Russia’s goals for the Minsk process, back in 2015.

Now, in 2019, it appears that President Zelenskyy is either oblivious to those goals or hopes that they can be changed after he personally meets Putin at a meeting in the Normandy format, which last took place in 2016. However, the chronology of initiatives to resolve the Russian-Ukrainian war we have studied here leave little foom for doubt that Minsk-2 is a trap for Ukraine, and Russia’s only goal is to destroy Ukraine from within using its ticking time bomb, the puppet “LDNR” which it aims to legalize as an autonomy.

Today, Poroshenko’s relatively innocuous amendments to the Constitution are off the table. As well, Zelenskyy has announced that a new law on the Special Status of Donbas will be drafted. This means Ukraine enters a zone of turbulence equal to that of 2015. It would be prudent for Zelenskyy’s administration to draw conclusions from the previous efforts to establish peace, and the hidden goals of the Kremlin revealed in Surkov’s emails.