This is the first time a significant troll farm has been revealed in Ukraine. What were the activities of the deleted accounts, groups, and pages and who was behind them?

Ukrainian investigative journalism project Slidstvo.Info conducted an undercover operation in cooperation with Hromadske, in which their journalist worked as a "bot" at Pragmatico's troll farm before the recent parliamentary elections. The investigation revealed the working process of the farm and some of its pre-election tasks.

Euromaidan Press has additionally talked to a former employee of the most popular Pragmatico's news website, Politeka, the page of which was shut down by Facebook together with fake accounts of Pragmatico's bots.

Gleicher describes the coordinated inauthentic behavior as a situation "when groups of pages or people work together to mislead audience who they are and what they are doing."

Facebook bases the decisions to remove such manipulative pages, groups, and accounts on their behavior, not the content they post.

"In each of these cases, the people behind this activity coordinated with one another and used fake accounts to misrepresent themselves, and that was the basis for our action," explained Mr. Gleicher.

Facebook removed 168 accounts, 149 Facebook Pages, and 79 Groups for "engaging in domestic-focused coordinated inauthentic behavior in Ukraine." Company's review linked their activity to Pragmatico, a Ukrainian PR firm.

The fake accounts were used to manage the groups and pages, disseminate content and to "drive people to off-platform sites posing as news outlets." In total, the removed pages had less than 4.2 million followers, the groups had 401,000 members. The troll farm spent about $1.6 mn on Facebook and Instagram ads paid for in US dollars.

As the screenshots attached to Facebook's press release show, the mentioned fake news outlets are Politeka, Znaj.ua, and Hyser. The groups and pages used to promote these websites are not available on Facebook anymore. One more screenshot featured a post of an account sharing a post from the site Akcenty. Its group having a mere 10 followers is still online.

According to Liga.Tech, the data of SimilarWeb show that Politeka received 12.3% of its visitors from social media among which the share of Facebook was 84%. Znaj's social media traffic share was 20% (with 88% FB's), Hyser about 14% (93% FB's).

Earlier Facebook revealed the companies similar to Pragmatico in Israel and the Philippines. As well as several Ukrainian Facebook groups were taken down which coordinated with Russia in its information war against Ukraine.

However, the Ukrainian company has no connection outside Ukraine and it doesn't cooperate with Russia, according to Liga.Tech citing Gleicher's comment. The PR company doesn't work for any particular politician or organization but took orders from various clients.

Troll farm from the inside

Slidstvo.info and Hromadske investigated how Pragmatico's troll farm worked and released the fifty-minute documentary 'I am a bot." The film features an undercover journalist of Slidstvo.info, Vasyl Bidun, who gets hired at the troll farm, shows his working process there and his comments about his duties as a "bot."

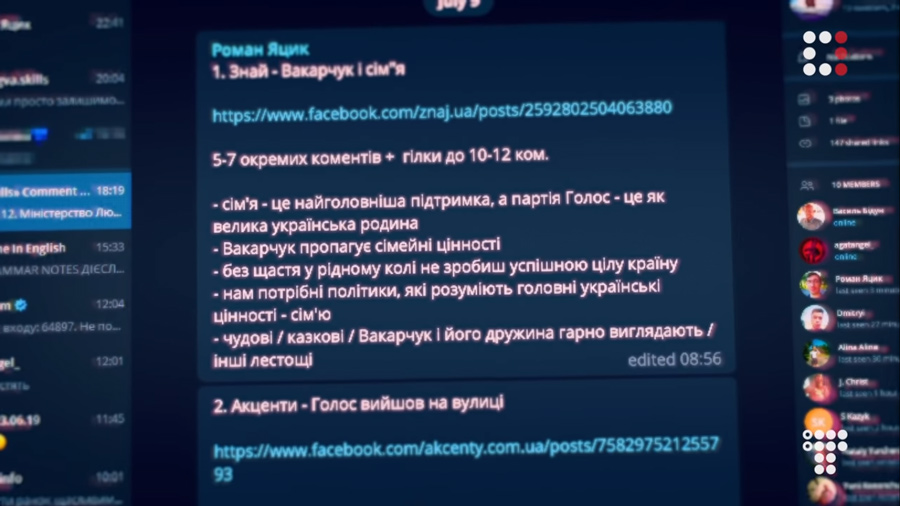

The investigation revealed that the troll farm uses the anonymous Telegram messenger for all communication between employees of the project on work matters.

The "bots" were online from 8 a.m. until midnight working in three shifts. Every day they receive half a dozen narratives to be pushed in the comments section under certain posts on social media using seven fake social media profiles per one operator. The daily plan for each bot operator is 300 comments in total.

The investigation shows that the farm published multiple comments on Facebook to support two candidates who later succeeded in getting into the parliament as majoritarian deputies. These were two persons displaced from the occupied territories of the Donbas - Donetsk comedian Serhiy Syvokho, Zelenskyy's friend who participated in his TV projects, and MP Serhiy Shakhov of Kadiivka (Luhansk Oblast).

A month before the parliamentary elections, a bot group was formed to support former defense minister Anatoliy Hrytsenko whose party Civil Position surveys put under the five-percent electoral threshold with about 2% ratings. The undercover journalist was instructed to hold fake discussions in comments between the accounts he operated, in which the account posing as Hrytsenko supporter had to be a winner. Together with it, all "bots" of the group were instructed to criticize Hrytsenko's key rival, former SBU chief Ihor Smeshko and his party Force and Honor. In total, the workers of the troll farm published 24,438 comments for the benefit of Hrytsenko.

Disguised as customers-to-be, the investigators were able to find the managing office of the company and met with political consultant Valery Savchuk, who bragged that Hrytsenko was a long-time client of the company.

On the 17th day before the elections, the group suddenly received instructions to stop commenting in favor of Hrytsenko. Around that day the surveys clearly showed that his party won't manage to pass the threshold, thus Hrytsenko could stop paying for further bot promotion.

A new task came for the group days later. The order was to support the party Voice and its leader Sviatoslav Vakarchuk, whom the same bot group blasted before over an argument with Hrytsenko on a TV show. The troll farm published more than 6,000 Vakarchuk-related positive comments in two weeks before the elections.

Holos barely passed the electoral threshold and got into the Rada. And Slidstvo's undercover journalist was transferred from a full-time job in the office of the troll farm to what they called freelance - working as a freelance bot at home.

In their comments to Slidstvo.info, both Hrytsenko and Vakarchuk denied using bots for promotion. As well as Syvokho's press service and Shakhov denied any knowledge of the bots.

The fact of using bots in favor of some politician doesn't necessarily mean that the person question hired them himself. For example, Syvokho ran for an MP for the first time in his life following a request of his friend, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, and Zelenskyy's HQ could be interested that the candidate from their party received a seat in the parliament. As well as the sudden bot support of Vakarchuk may mean that one of the parties which had ratings over the five-percent threshold - Zelenskyy's Sluha Narodu, Medvedchuk's Opposition Bloc For Life or Tymoshenko's Fatherland - saw him as a key rival of Poroshenko's European Solidarity (ES) and could have helped his party pass the threshold so that ES had fewer seats in the Rada.

Unfortunately, the investigation revealed the activities of only one group of Pragmatico's bots and it is unclear how far the scope of the company's activities reaches.

Fake news site from the inside

According to a national public opinion survey commissioned by the Ukrainian media watchdog Detector.Media, the website Politeka took fifth place among the most read and trusted Internet media in February 2019. Another one of Pragmatico's sites Znaj was 8th.

Speaking on the condition of anonymity, a former worker of Politeka told Euromaidan Press how the website operated. As in the case of the troll farm, the only communication tool between Politeka employees was Telegram. Every news editor had a daily posting norm of about 20 news messages, which had to be modified and extended according to certain search engine optimization rules.

The site's internal policies prescribed criticizing all politicians making exceptions only to two groups.

The first list included persons whose coverage should be exceptionally positive. On the second list were those who shouldn't be mentioned at all in the news reports. However, some politicians from both lists published so-called jeansa articles on the site - paid materials not marked as an advertisement or as a text provided by a certain politician.

The lists changed in time depending on the orders the company had at the moment.

For example, as of fall 2018, the "positive list" included Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Mikheil Saakashvili, Anatoliy Hrytsenko, Sviatoslav Vakarchuk, who all criticized then-president Petro Poroshenko. One more person on the list was MP Serhiy Shakhov, who was also promoted by the troll farm exposed by Slidstvo.info and Hromadske.

Sviatoslav Vakarchuk was later removed from the positive list, however, he returned there some two weeks before the parliamentary elections, according to the interlocutor of Euromaidan Press.

The not-to-mention list included among other persons Putin's Ukrainian crony Viktor Medvedchuk. By the end of the fall former prime-minister Yuliia Tymoshenko was added to it together with some other names.

At that period of time, criticizing then-president Petro Poroshenko, then prosecutor-general Yuriy Lutsenko, and interior minister Arsen Avakov was only allowed with references to other news. The latter condition could be a preventive measure to avoid possible persecution by the Security Service of Ukraine whose head is nominated by the president, the PG Office, and the Ministry of Interior.

As Politeka's worker noted to Euromaidan Press, the same or similar policies were applied to all other media projects as well. The people involved in such projects were employed off-the-books and had never heard the name of the company Pragmatico.

Euromaidan Press has checked two persons from the lists. Little known politician Serhiy Shakhov (Politeka's positive list) indeed gets most of his coverage in news on Znaj and Politeka and both websites present him exceptionally in a positive light.

Viktor Medvedchuk (do-not-mention list) has also been mentioned on both sites without any criticism or even opposing opinions. Moreover, most of the materials about Medvedchuk don't give references to any sources of the news unlike most of the site's regular news pieces.

An example of a typical jeansa piece is "At a personal meeting, Putin highly appreciated Medvedchuk's work on releasing people" about the meeting of Putin and Medvedchuk in the Russian city of Vladivostok, published on Politeka on 5 September 2019. Two days later the same article emerged on Znaj titled "Putin to Medvedchuk: You are succeeding in converting our good relations to humanitarian actions."

The text without any mention of its origin is written in an official style. It mostly consists of direct speeches with mutual praising of MP Mevedchuk and the Russian President. Medvedchuk hopes for extending economic ties between two countries, says that thanks Putin he and another pro-Russian MP, Vadym Rabinovych, had an opportunity to meet two Ukrainian prisoners, Karpiuk and Klykh, in a Russian prison and that they were glad to get "greetings from the Motherland" and "feel that they were not forgotten and there still are people who do their best for their release."

The article doesn't mention that Mykola Karpiuk and Stanislav Klykh were political prisoners who were sentenced in Russia under fabricated charges. The Russian aggression against Ukraine totally lacks from the article as well.

In their research published on 20 August 2019, Vox Ukraine and Artellence analyzed 10.37 million public comments posted between 1 May 2019 and 8 July 2019 in reply to Facebook posts on pages and groups of Ukrainian media sites.

The researchers defined eight features in online behavior and profile information that were more typical to online "bots" than to real persons and concluded that 3.38 million comments or 32.66% were allegedly posted by bots.

- The biggest share of the bot comments (over 50%) was on pages of less-known media having up to 200,000 followers on Facebook.

- On the most popular Facebook pages of the media outlets, the leaders of the bot commenting were RBC Ukraine (44%), Strana.ua 43%), Channel 112 (41%).

- Among top-five trusted media, most of the bot comments had Segodnya (39.8%) and Oborevatel (34.7%). The fifth most-trusted online media, Politeka, had only 22.71% of comments posted by bots, according to the research.

The research didn't intend to identify the location of bots and it is not known how many of the bot comments originated from Russia and how many were indigenous. The methods don't guarantee that all suspicious comments were actually posted by troll farms or that the percentage couldn't be actually higher.

However, the results of the research clearly show that political discussion among Ukrainian social media users is infested with fake accounts trying to push certain narratives in favor or against certain political forces. And the research allows making a suggestion that Pragmatico's troll farm taken down by Facebook is far from being the only one operating in Ukraine.

Read also:

- How Zelenskyy “hacked” Ukraine’s elections | Op-ed

- The Kremlin’s chaos strategy in Ukraine and its helpers

- Internet bots are key players in propelling disinformation: study of 9 countries

- Jeansa: vehicle of oligarchs, Ukraine’s largest threat to media freedom

- Bot accounts published 55% of Russian-language tweets about NATO in May-July

- “Novichok” and robots in social media

- Kremlin trolls exposed: Russia’s information war against Ukraine

- Russian trolls attack Americans

- Kremlin trolls are engaged in massive anti-Ukrainian propaganda in Poland

- Russia’s low-tech trolls in high-power western information space

- Russian trolls terrorize the West with old KGB methods

- Trolls on tour: how Kremlin money buys Western journalists

- Russian government Internet trolls effective in forming pro-Putin opinion among youth

- How Russian trolls are recruited, trained and deployed

- Putin trolls receive 20 million rubles to destabilize Peace March

- Fake info about “Ukrainian saboteurs” in Crimea in 2016 could have prompted Russian invasion of Ukraine