– What prompted Emperor Karl I to issue a manifesto proclaiming decentralization and the creation of a confederation?

– Franz Joseph, who embodied the golden age of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, had died several years before, on November 21, 1916, and the empire was threatened by internal conflicts, national ideals and the people’s desire for independence.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire turned out to be a colossus with feet of clay. Like other European empires, it was cracking at the seams, tottering, weak and holding on thanks to Germany’s support.

– The First World War was coming to an end… and Austria-Hungary was on the losing side…

– Yes, and the country was completely exhausted. Germany didn’t suffer so much from the military point of view – although they did have problems with food and supplies – but Austria-Hungary had enormous problems with refugees, devastated eastern territories, and it was faced with a much larger ethnic diversity than in the German Empire.

Accordingly, young national elites – first of all, the Czechs and the Poles – demanded greater privileges and self-determination. Karl I tried to save the empire, doing what could have been done in 1911-1914, when the national elites were still willing to compromise. In 1918, they no longer wanted to play along. Moreover, the Czech and Polish elites were largely oriented towards the Entente, the victors of the First World War.

The Czechs, Croats and Romanians were offended by the fact that Hungarians had been so privileged. Yes, the empire was federalized; national parliaments received the right to create a federation or even a confederation of national states. But, this proposal didn’t concern the Kingdom of Hungary, although there were many oppressed minorities within its borders: Ukrainians (Ruthenians), Slovaks, Romanians and Croats, all of whom who were considered Hungarian nationals.

Vienna, I mean the imperial court and the government, didn’t want to offend the Hungarians. As it turned out, the Hungarians were more than ready to bury the empire. Every Hungarian politician, every Hungarian teacher and every Hungarian officer had only one thought in mind: to create an independent Kingdom of Hungary, without Vienna.

– How did the people living on ethnic Ukrainian territories that were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire respond to Karl I’s proclamation?

– Let’s look at different factors. Today’s Zakarpattia Oblast (Transcarpathia) was part of the Kingdom of Hungary. There was no national Ukrainian elite. During the reign of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, the Hungarian government didn’t waste time and instigated a widespread program of Magyarization among the local elites and the population so that there were actually no leading Ukrainian public figures.

However, Bukovyna and Galicia (Halychyna), which were ruled by Austria, but under more liberal conditions, saw a rise in Ukrainian intellectual life and culture. Moreover, Galician and Bukovynian politicians were educated in classical imperial traditions. They were used to law and order: there had to be provisions, rules and regulations. There was no such anarchy as in the Dnipro part of Ukraine. They adopted Karl I’s imperial manifesto as a legal document and began to implement its provisions. A constituent assembly was convened – a meeting of representatives of Ukrainian parties, deputies of the Galician Seym and the Viennese Parliament. In other words, everyone wanted to proceed within the frame of the law.

In fact, the Ukrainian politicians of Galicia and Bukovyna hoped that they’d be able to work legitimately, in the spirit of the imperial manifesto.

– In other words, the Czechs and Poles didn’t look to Vienna, whereas the Galician and Bukovinian Ukrainians decided that this should be resolved through negotiations with Vienna?

– It wasn’t really so clear… It’s just that the Czechs were very offended, and had no politicians who were devoted to Vienna. Moreover Masaryk’s authority – he was still in exile and an ally of the Entente – was indisputable. That is, the Czechs had already pulled out of the Austrian Empire.

The Poles were somewhere close; they liquidated the Austro-Hungarian political system and established a Polish state. But, the formation of a Polish ideal and Polish statehood was just as chaotic as in Ukraine… because some territories of Austria-Hungary were occupied by Germany, but belonged to the Russian Empire. It was the Regency Kingdom of Poland, a proposed puppet state of the German Empire during WW1 where Poles occupied some meaningless positions in the cultural and educational sphere, but the real policies and economics were run by German officials.

– At some point, Ukrainians also decided to act. Due to changes that took place in these years, going from the legitimate to the revolutionary, the “Lystopadovy Chyn” (November Revolution) took place in Lviv: on the night of October 31 to November 1, 1918, Ukrainians gathered in Lviv National House and proclaimed the West Ukrainian National Republic.

How did this happen? At first, the Ukrainian elite promoted negotiations with Vienna, and then, suddenly they decided to destroy Austria’s authority and proclaim a Ukrainian state?

– I wouldn’t say that there was a real change in their outlook. The older generation of Galician politicians remained true to this approach. November 1 doesn’t mark the proclamation of the West Ukrainian National Republic, but the transition of power to Ukrainians. On October 19, 1918, it was proclaimed that Ukrainians could create their own state within the framework of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. And, only from November 9 to 13 was the West Ukrainian National Republic proclaimed, relevant normative acts adopted, etc.

That is, this was the “November Revolution” or “coup”… in the interwar period; this word was used to mark a momentous event…

– Yes, indeed, it was a momentous event! Ukrainians went to sleep under Austrian rule, and woke up under Ukrainian control!

– Absolutely. But, I can’t say that the paradigm changed, but it all happened thanks to young blood!

Young Ukrainian officers, who had spent their childhood in Ukrainian youth organizations, and their adolescence/young adulthood in the trenches of the First World War, understood that the Poles wouldn’t give up Lviv. Suddenly, they learn that the Polish Liquidation Commission is scheduled to arrive in Lviv to establish contacts with the Austrian governor in Galicia and sign a document transferring power and authority to the Polish government.

These young Ukrainian officers meet with the older Ukrainian politicians on October 31 and say: “Unless you do something, the Poles will take over everything that you want to establish legally sometime in the future. They’re arriving on November 2 or 3, so we must act immediately!”

These young Ukrainian officers simply put the older politicians before the fact: either we take power and control, or nothing will happen.

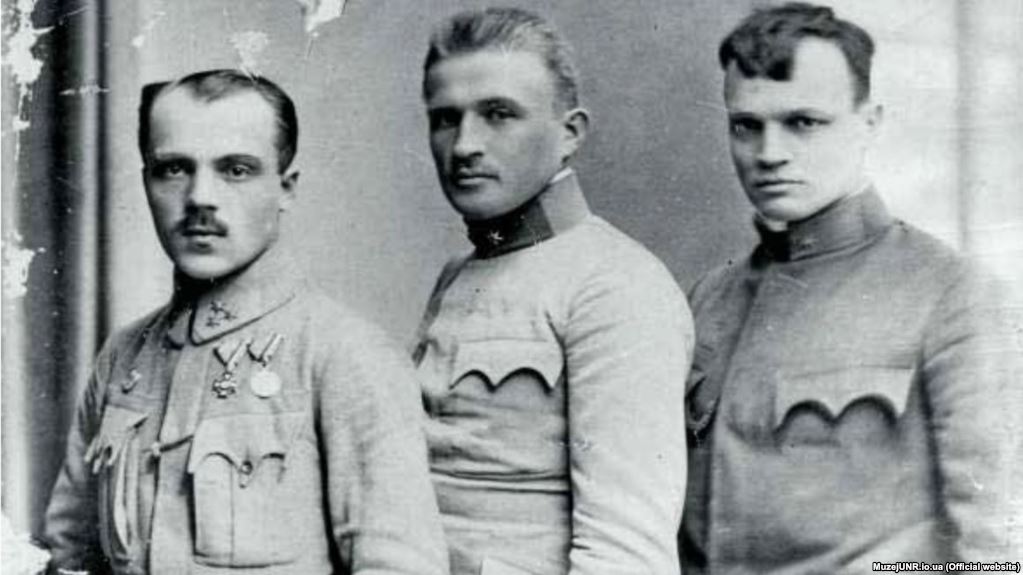

– These young officers drew up a new agenda for the older politicians. Sotnyk Dmytro Vitovsky played a leading role, and thanks to this successful operation, he was immediately promoted to the rank of colonel. Many Ukrainian officers – and, there were dozens of officers and several hundred Ukrainian soldiers – thought it was a hopeless situation, and some even drew up their last will and testament, because they thought they would die fighting for their ideal. So, why was it so easy – on the night of October 31 to November 1, 1918 – to take control of Lviv, and subsequently of Eastern Galicia?

– Connections had been established with Ukrainian organizations, committees, and representations in all the cities, towns and villages of Galicia. They instructed the locals to take control of the councils, hang flags on the town halls, and take over the railway stations and military barracks. It all happened during the night leading to November 1.

Why did the revolt succeed? Of course, it was largely due to Vitovsky’s incredible energy and leadership, and to the officers that followed him. The Ukrainian movement was more or less organized. People knew each other; they communicated within the framework of public organizations; they trusted one another, and once the process was launched, nobody could stop it!

A very important role was played by partisans from the Ukrainian underground military organization, who managed to persuade the Hungarian and German military units in Lviv not to interfere. These units were so strong, with so many men, that no one could have resisted them: neither the Ukrainians nor the Poles.

“We’re ready to negotiate; we promise we won’t touch you, but we’re taking everything under our control on legal grounds, because a manifesto was proclaimed by the Emperor. You all want to return home, but if you start putting up a fight, then we’ll destroy the railway lines, and make sure that you don’t get to Budapest or Vienna.” said the young Ukrainian fighters.

So, these units remained neutral; they didn’t react at all. This is also a genial example of organization and planning: some Ukrainian soldiers took over the post and telegraph office, others – the train station, etc. It was really a manifestation of wild energy and brilliantly organized!

How did the Austrian governor, General Karl von Huhn, react to the seizure of power by these Ukrainians troops?

– He was surprised, somewhat shocked that his orders hadn’t been followed to the letter and junior officers had been allowed such antics. But, he kept his calm, did not order his troops to resist, and his soldiers didn’t leave the barracks. He then signed a document transferring authority to officer Detsykevych, his Ukrainian deputy. Therefore, the Austrian authorities transferred authority and control both legally and formally to the Galician politicians. If we look at it from the legal point of view, the West Ukrainian National Republic was created legally.

– The West Ukrainian National Republic was proclaimed on November 1, 1918 with Lviv as its capital. But, as far as I understand, the proclamation of the Republic – which claimed sovereignty over largely Ukrainian-populated territories – was a complete surprise for the Poles, who constituted a majority in the city.

– Yes, that’s true. But, the population of Lviv also included a large percentage of Jews, as well as many Ukrainians, Germans, and an important Armenian community. The Poles disagreed, but they were just as divided as the Ukrainians, with several leaders. In essence, they were waiting for someone to come and organize them… and then, everything would be resolved. They didn’t take Ukrainians, whom they called Rusyny, very seriously. They said: “Okay, these Ukrainians have a few writers and some newspapers, but they aren’t capable of achieving anything; they are, in fact, backward peasants.”

The Poles believed that they’d get everything from the Austrians. So, they were in shock when they realized that the Ukrainians had not only stood up for their rights, but had also showed their claws. Suddenly, there were policeman patrolling the streets with blue-and-yellow armbands, blue-and-yellow flags everywhere…

In the beginning, Polish officers organized volunteer troops in Lviv. It was, in fact, urban warfare where armed groups moved from one building to the next, one street to the next.

These Polish officers were also ordinary citizens; they had also joined their own youth organizations in the early 20th century and gained experience in the trenches of the First World War. These lieutenants, captains, majors included many volunteers, mostly boy scouts, students and youngsters. We all know the legend of the “Lwow Eaglets”* that defended Polish Lviv? If we study some diaries and memoirs written by Polish officers who resided in Lviv, they were not burning with desire to go to war; they didn’t understand what they’d be fighting for!

* The “Lwow Eaglets” were young Polish volunteers, who participated in the fights within the city of Lviv between November 1 and November 22, 1918, and the following siege by the Ukrainian Army between November 23, 1918 and May 22, 1919. With time, however, the term’s application was broadened, and it is now used for all the young soldiers who fought in Eastern Galicia for the Polish cause in the Polish-Ukrainian War and the Polish-Bolshevik War-Ed.

As a matter of fact, many Polish soldiers thought that it wasn’t “their war”. Some Polish organizations declared a general mobilization. Young patriots, individual officers, and so-called “batyars” – semi-criminal elements from the city outskirts – joined the fight until regular troops arrived from Poland to fight the Ukrainians. Poles living in Lviv looked on and said: “What a shame! The Rusyny (Ruthenians/Ukrainians) have seized power!”, but no one was in a particular hurry to fight.

– If the Poles were so skeptic, then why did the Ukrainians hold Lviv for only three weeks?

– Regular Polish military units started arriving from the district of Krakow, and then from Greater Poland. The Ukrainian government counted on several strategic points: they didn’t have time to bring in the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen as quickly as needed, and so the Polish units were able to capture the railway station.

– So, where were the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen at that moment?

– In Bukovyna, engaged in another conflict: some of the Sich Riflemen refused to go to Lviv, so only a few units departed for the city. This was poorly managed, and not enough propaganda was spread to the other Ukrainian regions. Consequently, many Ukrainians who had served in the Austrian Army grabbed their rifles and simply went home to their respective villages, believing that Lviv had already been taken by Ukrainian patriots and that a Ukrainian government was in place.

– Then, men started deserting…?

– Yes, But, these men hadn’t yet sworn allegiance to the Ukrainian state. They thought that the Austrian Empire had collapsed, that the Austrian army was no more, so they picked up their rifles and headed home. Therefore, there was a problem with reserve troops, whereas the Poles, on the contrary, increased their reserve troops and weapons. Perhaps the Ukrainians could have won if they’d blown up the bridges crossing the Sian River in Peremyshl (today’s Przemysl in Poland-Ed) in early November. The Poles captured these bridges and soon afterwards, they were able to send in more troops and weapons by rail.

– There are a lot of “if only-s”: if only the Ukrainian politicians hadn’t squabbled so much with each other, if only they’d known how to behave and react consistently, if only they’d negotiated or asked for help… there were too many negative factors involved.

– During the Polish-Ukrainian War of November 1918 and 1919, the army of the West Ukrainian National Republic was able to hold off Poland for approximately nine months, but by July 1919, Polish forces had taken over most of the territory claimed by the West Ukrainian National Republic.