On 2 October, the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Stratcom Ukraine announced the launch of a campaign in which it will ask international media to use the spelling "Kyiv" for the country's capital instead of "Kiev."

The Ukrainian MFA will monitor the materials of international English-language media such as the New York Times, BBC, Reuters etc and send them tweets urging to use "Kyiv," the spelling transcribed from the Ukrainian language, in their materials, using the hashtags #KyivNotKiev, #CorrectUA.

"In accordance with the 10th United Nations Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names, we politely request all countries and organisations to review and where necessary, amend their usage of outdated, Soviet-era placenames when referring to Ukraine," said the MFA in a statement on their website.

At that conference, the “Romanization system in Ukraine” was recommended as the international system for the transliterations of Ukrainian geographical names. Despite this, the Russian-form transliterations are still being extensively used, which the MFA considers to be a relict of the Soviet Era.

Some of the most misspelled Ukrainian toponyms, with transliterations mistakenly based on the Russian form of the name, are:

|

Ukrainian spelling |

Archaic Soviet-era spelling |

|

Ukraine |

The Ukraine |

|

Kyiv |

Kiev |

|

Lviv |

Lvov |

|

Odesa |

Odesa |

|

Kharkiv |

Kharkov |

|

Luhansk |

Luhansk |

|

Chernivtsi |

Chernovtsy |

|

Mykolaiv |

Nikolaev |

|

Rivne |

Rovno |

|

Ternopil |

Ternopol |

The case for decolonization

"Kyiv not Kiev" resonates with many Ukrainians. After all, the Russian Empire and later, the USSR, had used Russification to extinguish the identities of individual nations, portraying their languages as secondary and insufficiently civilized. Over the 337 years that Ukraine was under foreign rule, there have been 60 prohibitions of the Ukrainian language - meaning state bans on its usage. It is no wonder that with Russia's new neocolonialist intervention in Ukraine, the fight for Ukrainian sovereignty has spilled out to the language battleground with a new ferocity.

Read also: A short guide to the linguicide of the Ukrainian language.

"Kiev" more widespread, "Kyiv" - official

It was the Ukrainian independence and adoption of Ukrainian as the official state language in 1992 that prompted an international change in the use of Ukrainian toponyms. "Kyiv" has been the official spelling of the country's capital since 1995. It has been adopted by the UN and is used in international relations and cartography in English-speaking countries.

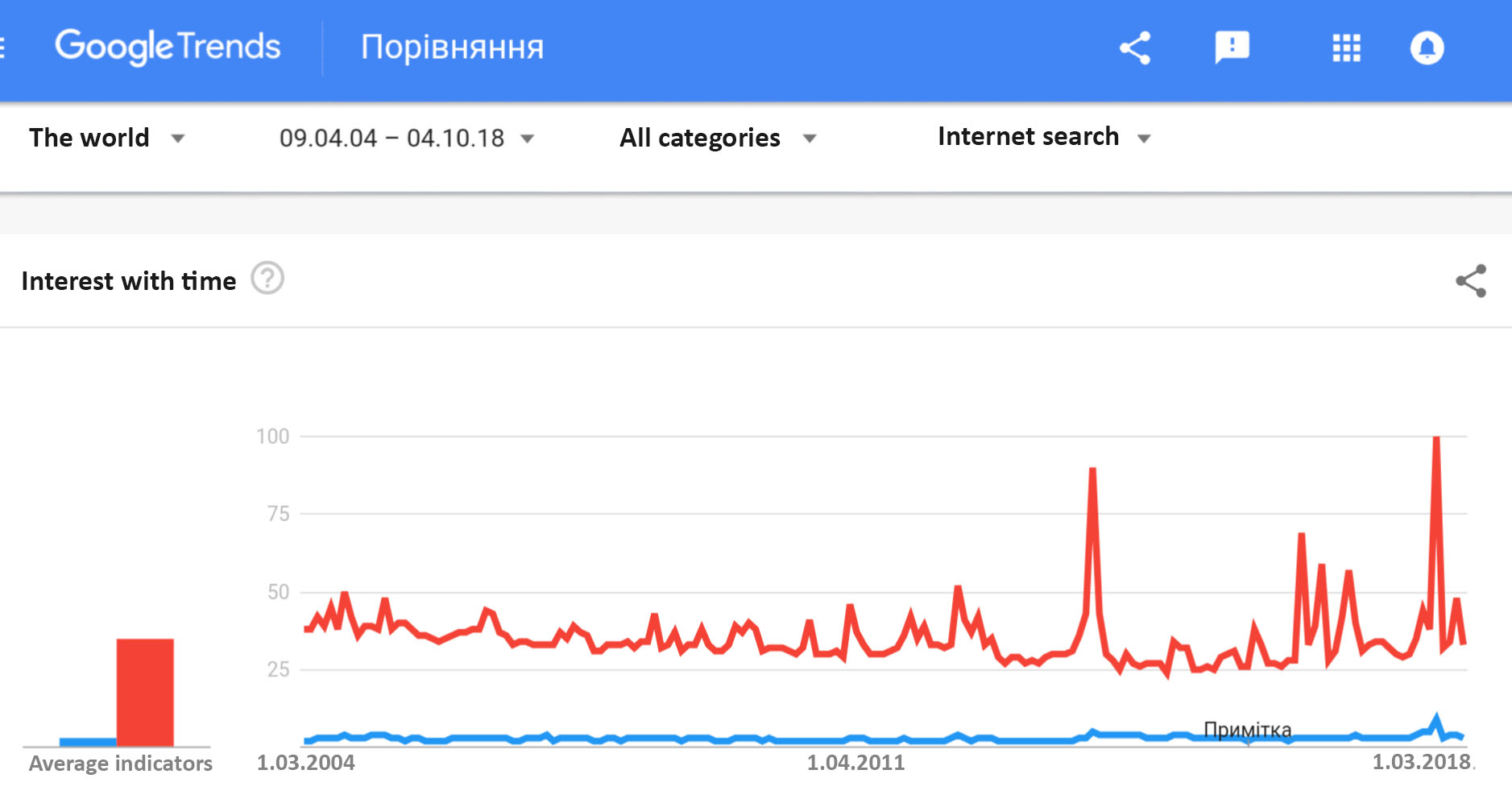

Although, as the Ukrainian MFA pointed out, the UN standard for geographical names is to use the latinize of the official spelling of the toponyms in the local official language, Ukrainian, the transcription of Russian "Киев - Kiev" is far more widespread than that the Ukrainian "Київ- Kyiv." According to a Google trends comparison of search queries, searchers for "Kiev" have been ten times more numerous than for "Kyiv" over 2004-2018.

A Google trends analysis of search queries for "Kyiv" and "Kiev" over 2004-2018. Photo: Euromaidan Press

However, the popularity of "Kiev" isn't as ancient as one might think. Just 300 year ago, the nameforms Kiou, Kiow, Kief, and Kiovia were in the trends, as a search of English-language books in Google NGrams shows.

One of the reasons Kiev overshadows Kyiv today is that the former is used by most international media, which argue that this is the spelling which is more familiar to English readers and that it is not Russian but the accepted English spelling of the name.

For instance, in 2010, Robert Basler wrote about the yi vs. ie

for Reuters:

We try to communicate with readers using geographic names they commonly understand.

Changes in our style do occur, but the timing is always a judgment call. It’s difficult to know precisely when Peking becomes Beijing, Burma becomes Myanmar, Cambodia becomes Kampuchea and then Cambodia again.

Kiev is not the Russian spelling. It is the commonly accepted English language spelling of the name.

John Daniszewski, senior managing editor for international news with the Associated Press, explained why they chose to stick with Kiev in 2014, in an e-mail to Poynter.

We have looked at it in the past and opted on the side of “Kiev” because we believed, at that time, that the preponderance of usage and the way most Americans and English speakers understood the name was “Kiev” and the alternative spelling might cause confusion. We do not always go with local spellings of course. We do not spell Warsaw as Warszawa or Moscow as Moskva, for instance.

However, given the dynamic of the last few weeks and Ukraine’s strong assertion of Kyiv as the preferred spelling of its capital and the popularization of that spelling, Stylebook editors are likely to look at the question again in the near future.

Although the argument that the English spell Rome not Roma, Prague not Praha, and Florence not Firenze is seemingly a compelling one, it differs from the Kyiv-Kiev debate. The Italians and Czechs are not accusing the English-language spellings of the names of their cities of being a vehicle for English - or any - imperialism.

In Ukraine, that is not the case.

The ideological underpinnings for Russia's occupation of Crimea and covert war in eastern Ukraine lie in the denial of Ukrainian statehood. Russia insists it has a right to determine the destiny of its former colony. And that is the main idea it attempts to impose on the international arena, frequently articulated in the postulates of so-called realpolitik: that as soon as the West accepts Ukraine as belonging to Russia's sphere of interests, West-Russian problems will subside and all will be well. The use of "Kiev" over "Kyiv" intuitively confers an air of legitimacy to Russia's claims to Ukraine.

Russia's denial of Ukraine's very right to exist as a separate country is at the heart of the seemingly linguistic debate. The use of "Byelorussia" over "Belarus" carries a similar meaning.

While editorial guidebooks are conservative, they too change, in line with burning political issues of the day, such as the term "illegal immigrant" and pro-life/pro-choice and anti-abortion/abortion rights language. What matters is the scale of the debate.

And raising the scale of the debate is what the Ukrainian MFA aims to achieve.