This week Ukrainians and all people of goodwill around the world are marking the 85th anniversary of the beginning of the Holodomor in 1932, the terror famine organized by Stalin and the Soviet system that killed more than five million Ukrainian peasants.

More than three out of four Ukrainians now view that event as a Russian genocide against their nation as do an increasing number of people and governments around the world (gordonua.com).

But in focusing on this horror, one that has come to be better appreciated internationally thanks to the heroic efforts of Robert Conquest and Anne Applebaum, it is important to remember two other things.

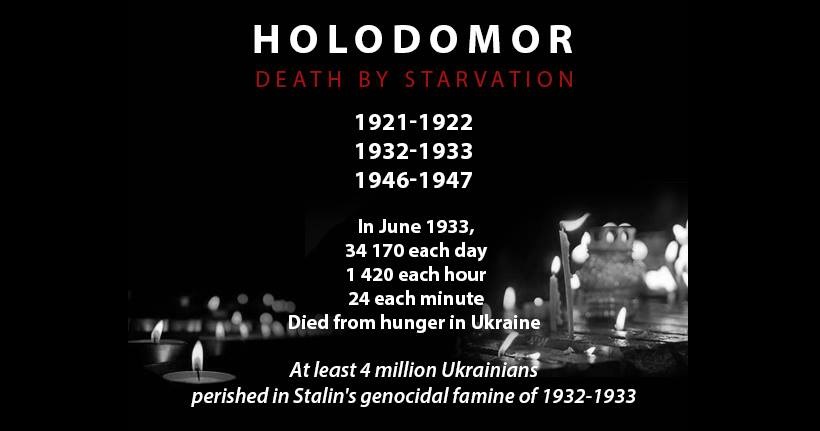

On the one hand, as Ukrainian Prime Minister Volodymyr Groysman points out, the Ukrainian people suffered not one Holodomor but three.

In a statement, Groysman points out that on the fourth Saturday of November, Ukrainians pause to remember the victims of the mass hunger Moscow used against Ukraine in 1921-23, 1932-33, and 1946-47 as a form of “ethnic cleansing” designed to achieve “the destruction of the entire people” (kmu.gov.ua).

The Holodomor of 1932-33 is better known and far better documented as an action of state-sponsored genocide against the Ukrainian nation; but Groysman is certainly correct that the two other terror famines reflected state policy and could have been avoided if Moscow had been more concerned about the population than about exporting its revolution.

And on the other hand, while it is entirely natural that the victims of genocides should focus on their own national tragedies, it is also important to remember that these three terror famines under the Soviets carried off millions of other victims in Belarus, the North Caucasus, the Volga region, the Southern Urals, Kazakhstan and elsewhere.

Russian historians often try to minimize the genocidal aspects of the Holodomor in Ukraine by suggesting that the causes of the famines there did not reflect any ethnic animus on the part of Soviet leaders but rather were the product of broader problems and policies like dislocation after wars and collectivization (lenta.ru).

To honor the memory of the Ukrainian victims of the three Holodomors inflicted on them, however, is in no way lessened by recognizing the terror famines inflicted on others by the Soviet regime. Instead, it is increased because it shows that Ukrainians have moved beyond the notion that they or any other group is a unique victim.

Instead, the Ukrainians in this way can demonstrate that something evil remains evil regardless of who carries it out and against whom it is directed rather than being contingent on one or the other. And that puts them on the way to fulfilling the great Russian memoirist Nadezhda Mandelshtam’s standard for a truly good and happy country.

As she wrote so many years ago, “happy is the country where the despicable will at least be despised.” That is something Ukrainians and some others are capable of. Unfortunately, it is not something that everyone else yet is.

Read More:

- Ukraine suffered the most deaths in the Holodomor while Kazakhstan had the highest percentage loss of population

- How Stalin starved 1930’s rural Ukraine to quash political enemies: Anne Applebaum interview

- History as a weapon in Russia’s war on Ukraine

- The Holodomor of 1932-33. Why Stalin feared Ukrainians

- HOLODOMOR 1933: Light a candle in your window

- Documents reveal Soviet repressions against those resisting Holodomor genocidal famine

- Why compare the Holodomor and the Holocaust

- Holodomor or death by starvation changes people’s genotype, say psychologists

- Documents show massive export of products from Ukraine during Holodomor

- History, Identity and Holodomor Denial: Russia’s continued assault on Ukraine

- Holodomor: Stalin’s genocidal famine of 1932-1933 | Infographic

- Stalin’s genocidal Holodomor campaign of 1932-33. What we know vs the denialist lies