International correspondents often cite the difficult role objectivity plays while covering terrorism, since the nature and genesis of media coverage is often prone to sensationalism. Yet, if exercised with professionalism and integrity, freedom of the press ought to be one of the most cherished rights in all democracies.

Chechen rebels in Russia infused the specter of terrorism to their operations during the 1990s and also in the early 2000s, forcing the Russian government to employ a fierce counter-terrorism strategy. During one of its operations, in the 2nd Chechen War, it was the journalistic work of intrepid Russian reporter Anna Politkovskaya who gave a voice to her country’s enemies, which in turn, made her an enemy of her own more authoritarian government, headed by Vladimir Putin. Since assuming power, Putin has compromised the international tenets of journalism through accepted draconian policies, and the effective moral dilemmas created by a quest for “ultimate” security.

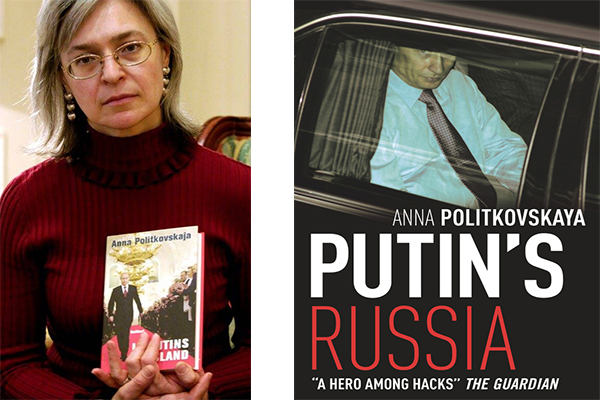

Politkovskaya covered the rise and reign of Putin, and became a virulent critic of his counter-terror methods against Chechen rebels, often cited as terrorists, and how he chose to rule Russia. Politkovskaya spent much of her journalism career covering the war in Chechnya, and Putin’s fierce grip on power. She was killed in the elevator of her own Moscow apartment building on October 7, 2006 - Putin's birthday - in a murder still unsolved. Many believe Russian authorities were behind her murder, or perhaps it was a gift offered by the installed leader of Chechnya, Razman Kadyrov who was handpicked by Putin himself.

Although Politkovskaya did not apologize for “terrorists,” she was certainly condemned for it.

Politkovskaya covered the Chechen war between 2002-2004 in her newspaper Novaya Gazeta and later chronicled in her book, A Small Corner of Hell: Dispatches from Chechnya. She recorded the supposed unlawfulness committed by Russian soldiers, who sought to "obliterate" Chechen fighters. This was the message that came directly from Putin.

Politkovskaya’s candid accounts likely riled Russian authorities, which were waging its “war on terror.” It was Putin who set up a counter-terrorist apparatus in place against the Chechens when he became president in 2000, and his methods were meant to disrupt their capabilities.

Politkovskaya was consistently at odds with Putin’s "war on terror” methods, as she elucidated in her columns, and later in her books, depicting a ruthless former KGB officer and head of the Federal Security Service (FSB) as a hybrid system, in which democracy in Russia was impeded. She saw Putin as tyrant, egregiously overstepping the rule of law.

Politkovskaya’s work with the newspaper Novaya Gazeta investigated the crimes and human rights abuses of the federal and Moscow-installed authorities in Chechnya and in Russia, as well. She was a consistently outspoken critic of the war in Chechnya, and she often gave first-hand testimony of villagers in Grozny or other cities in Chechnya.

When Putin launched an overwhelming military campaign there, it was conducted under the label of an anti-terrorist operation but she reported it as, "the start of a second brutal war killed as many as one-hundred thousand people.”

Since assuming office in 2000, Putin set in motion a counterterrorism initiative against Islamists who were seeking a separate state. He centralized his power to conduct the battle of international terrorism and religious fanatics. Some feared this was merely a ploy to prove he was a stalwart buttress against Islamic extremism, absolving himself and his military apparatus from violations of torture and other questionable tactics. It is true that during his tenure, Chechen terrorist attacks in Russia were rampant, underscoring the need for heightened security measures.

Once Russia established direct rule of Chechnya in May 2000, Chechen militant resistance throughout the North Caucasus region continued to inflict heavy Russian casualties, and the number of terrorist attacks increased. As a result, both Chechen terrorism as well as widespread human rights violations by Russian and separatist forces, equally drew international condemnation. It is possible to view the blurring of the lines between the needs for security with open and transparent reporting.

Putin built his career as a proponent of security as the backbone of his presidency, positioning himself in the global fight against terrorism, aligning himself with then-US President George W. Bush in the post-September 11 era. Putin used his experience as an officer in the Committee for State Security (better known as KGB), to control all of Russia’s federal politics.

Politkovskaya’s career as a war correspondent in Chechnya, and her reportage on Russia’s counter-terrorist methods, meanwhile, did not win her any government friends. Just days after her mysterious murder, according to Russian newspapers, Putin was quoted as saying, that she “brought more damage to Russia by her death than by her work,” raising the question evermore about who killed her. It was universally accepted that her expose of the crisis in Chechnya was a threat to Putin’s view of homeland security.

Putin’s oblique - and insensitive - remark about Politkovskaya's legacy has only drawn more scrutiny in the subsequent years, to who may have been the mastermind.

"The retrial, which has not started in earnest, was assembled in a very wrong track," Nina Ognianova, the Committee To Protect Journalists' Eurasian Director told me in 2014. "There was a question whether the right defendants were on the stand, and where is the mastermind? In fact, the mastermind, and the motive in the killing has never been publicly reported on, nor established by [the Putin] government. And before that happens, any other developments, pale in comparison because this is the trend in Russia: you may net the small fish but not the commissioners of the crime."

In light of this specter of terrorism, journalists have not been protected. More than a dozen Russian journalists have been killed during the tenure of Putin.

Oksana Chelysheva, who is both a journalist and human rights activist, once described

Putin’s Russia as

“moving toward autocracy. Few signs of real democracy survive. Anna Politkovskaya was one of the toughest critics of the current state of things here in Russia and the situation in the North Caucuses. She revealed a lot of crimes, in which both pro-Moscow Chechen armed forces and federal agents were involved."

In A Small Corner of Hell: Dispatches from Chechnya, Politkovskaya highlighted the brutality of the Russian invasion into Chechnya, as Putin’s guise to wage an anti-terror campaign, stripping journalists' abilities to objectively cover the war. She exposed the brutalities of the war in stark terms, and wrote about torture and war crimes that may have been conducted by Russian authorities. Putin’s imprints were behind it, suggested Politkovskaya.

“Life in Grozny (Chechnya) falls into two categories: ‘free and ‘blockaded,’ wrote Politkovskaya. “There has been a disproportionately large military contingent of nearly one hundred thousand, opposing the Chechen population of six hundred thousand through murders, torture, and kidnapping… the purges continue, the commerce in living and dead bodies by soldiers as the principal military operation in Chechnya hasn’t ended, and thousands of people search for their kidnapped relatives and, in the best case, ransom, their corpses from those who defend the Motherland from terrorism.”

She continued:

“There is only one principle guiding the birth of these fighters: the more people get humiliated and hurt, the more units are formed. These units were born in the war, recruiting from Chechens who never thought of fighting before and were even hoping for the Russian troops to come and liberate them from the Wahhabis. Mostly the army inside Chechnya supports small units. Of course there is a more precise description of the situation: its secret financing of the Chechen civil war is in connection with antiterrorist needs. Any secret service in the world would verify that it is better to destroy the enemy by someone else’s hands than your own. This idyllic coexistence is, of course, quite unique in Chechnya… Kremlin’s control of the smoldering conflict in Northern Caucasus is its main governmental policy… there are more and more corpses every day.”

Politkovskaya depicted Putin as a ruthless dictator, consistently manipulating his role as leader, and in effect, forsaking his country’s democracy, in support of a consolidation of power.

Putin was elected president in 2000, after serving as a vital officer in the KGB. At the same time, the Federal Security Service (FSB) rose to prominence. He then had rested his candidacy on security, to thwart terrorist attacks by Chechens. At the time, the FSB hunted down foreign spies with any links to Chechen terrorists. This would soon get murkier, and more corrupt, as

“the rule of law remains a distant goal in today’s Russia, where the security services have concluded that their interests, and those of the state they are guarding, remain above the law," Politkovskaya wrote in her book. "The mindset of Russia’s security services has undeniably been shaped by Tsarist and Soviet history: they are suspicious, inward looking, and clannish…”

Over a decade has past since Politkovskaya's murder, and while Russia's strict laws against investigative reporting remains unabated, freedom of expression there is not completely curtailed. "There are lawyers [which try to] protect freedom of expression in Russia," Vitaly Chelyshev, a former reporter in Moscow told me. "Journalists in Russia [write] openly, but more often on the Internet. There is a free media, but very small. There are a few newspapers; some radio stations, and several television stations." Chelyshev added that the journalism community continues to fight against censorship laws within its media.

In short, Politkovskaya underscored that Russia prioritized national security over civil rights. Her murder remains a tragedy, riddled with mystery, begging the question whether journalists can be objective and protected by democracies in an age of terrorism. Democratic governments must uphold the right of free press; yet it did not protect Anna Politkovskaya. Her death remains a painful blight on Russia, even as it continues to rebrand itself as a flourishing, democratic society.

Related: