In 1970, Robert Sherill published a harsh critique of the US military’s justice system under the title Military Justice is to Justice What Military Music is to Music. Now, after Vladimir Putin has refused to extend the power-sharing accord with Kazan, one can say that Russian federalism has even less connection to genuine federalism.

That is, some of the same words and music are used to describe it, but the content and meaning are entirely different, something many in Russia’s regions and republics are horrified by, but that what Russian centralizers are now celebrating, because they want all decisions to be made by Moscow officials rather than by Russians and non-Russians beyond Moscow's ring road.

On Monday, the ten-year extension of the Moscow-Kazan power-sharing accord ran out. Tatarstan officials called for its renewal, but the Kremlin ignored their request, except to have Putin declare that it was constitutionally wrong to require Russian speakers in republics to learn the titular language, something that accord had enshrined and that Russian courts had accepted.

In an article celebrating the end of the power-sharing agreement, Svobodnaya pressa commentator Aleksey Polubota and those Moscow commentators with whom he spoke declared that Russia as a result had “finally overcome a dangerous inheritance from the Yeltsin era in nationality policy.”

The writer quoted Russian nationalist publicist Yegor Kholmogorov as saying that as a result, “Russia had formally been transformed into a single state without treaty elements in its federal structure” and this represented “of course, only the first step to a genuinely united Russia.”

Polubota asked two other Moscow writers what the end of the power-sharing accord means and what is likely to happen next. Mikhail Remizov, president of the Institute for National Strategy, said that he welcomed the end of the accord because it would allow Moscow to end the discrimination Russians and Russian speakers now experience in non-Russian areas.

But Remizov continued, it highlights something else even more significant: “Our country,” he remarked, “is a constitutional federation and not a treaty one. That is, from the outset, Russia was not a country created by various territories which agreed that now we will exist together, each on its own basis.”

Rather, “the logic was just the reverse: from the outset, a single unitary country formed various subjects of the federation.” That principle must be maintained, and in that regard, “the special agreement with Tatarstan was an unnecessary and even dangerous exception” that has now been eliminated.

“In the early 1990s, the constitutional disintegration of Russia took place in which dozens of the subjects of the federation sought to obtain for themselves special conditions from the federal center.” That must not continue. Russian speakers in the republics must not be compelled to learn non-Russian languages, and republics must not be allowed to have presidents.

On those issues, there can’t be any compromise, Remizov said. All regions must be the same in terms of law and practice, and then all can be strengthened so as to strengthen the country. Their “strengthening,” including a nod toward “budgetary federalism,” he added, “corresponds to the interests of the country as a whole.”

Now that the Moscow-Kazan treaty is a thing of the past, he argued, “we must first of all move toward the equalization of the status of regions.” That won’t ever be completely achieved, but Remizov suggested that what is sometimes called Russia’s “excessive centralization” is “a means of compensating for the inequality of the regions.”

Eliminate the one and the other will be eliminated as well, he implied.

Toward that end, Remizov argued, “the administrative borders in Russia” should be redrawn to correspond with socio-economic needs rather than “on an ethnic basis.” That will mean fewer federal subjects but more effective ones. Unfortunately, there is a great deal of work to be done on that and no one is yet focused on it.

A second researcher with whom Polubota spoke was Oleg Nemensky of Moscow’s Russian Institute for Strategic Research [the institute is a part of Putin's presidential administration - Ed.]. Noting that the power-sharing accord didn’t contain much of importance, he argued that nonetheless it was “a very serious threat to the unity of Russia.”

Even without the accord, however, “the danger of the disintegration of Russia has not disappeared, although it has been reduced.” Consequently, further steps must be taken and soon to “form relations between the center and the regions which will block the development of centrifugal forces” that could emerge in a “political or economic crisis.”

To that end, Nemensky continued, “the federal center must increase the number of levers with the help of which it will be possible to influence the situation of inter-ethnic relations in all the republics and oblasts of Russia.” Moreover, Moscow must work to ensure that laws in all are “unified to the maximum degree possible.”

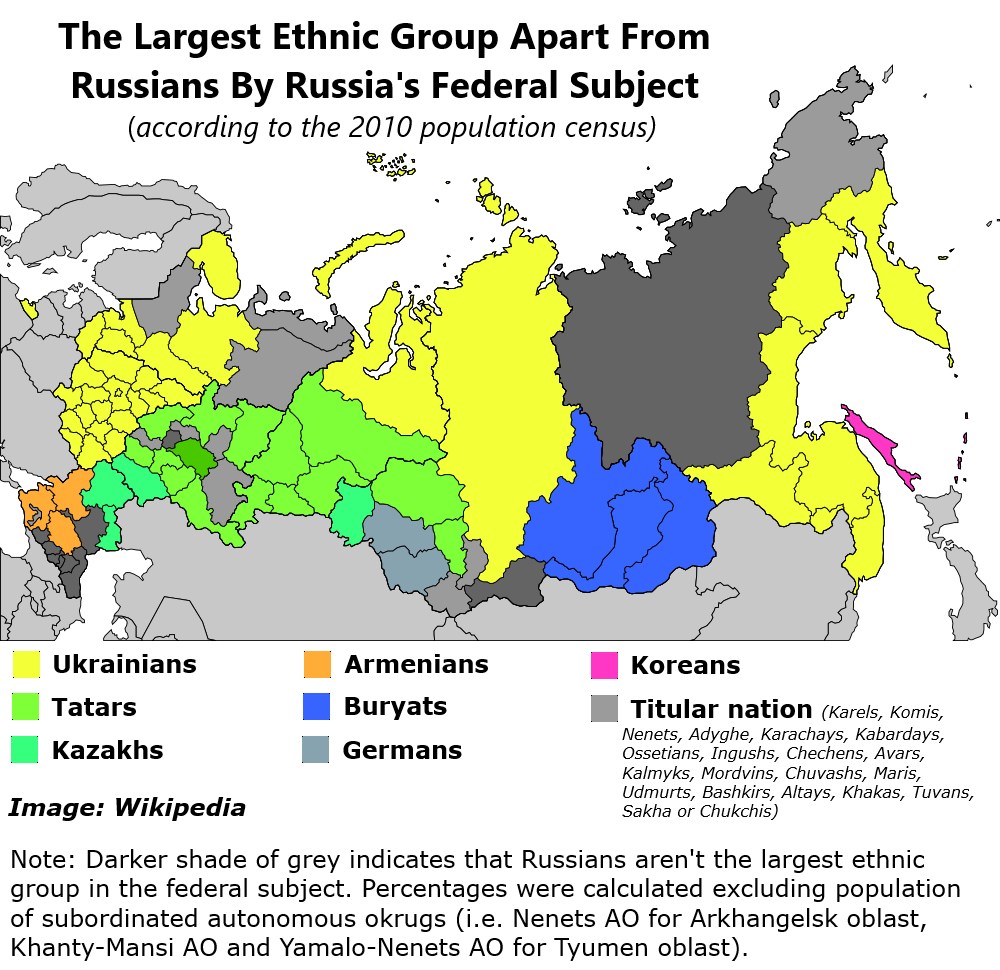

“This is particularly important in national republics where ethnic Russians are the majority but where representatives of the titular nationality are more heavily represented in government, in business and so on.” There now must be “special laws” about national minorities wherever they live.

In reporting these and even more radical Russian nationalist proposals now that the treaty has lapsed, Kazan’s Business Gazeta notes that some of them include calls for “transforming Tatarstan into the Kazan oblast” and stripping it of all independent powers.

As of now, the paper says, “plans for the deconstruction of [the Tatar] nation” are still those of “marginal figures.” But it warns that no one can tell how long it will be before such ideas become centerpieces of Moscow’s policy.

Related:

- ‘If a bourgeois revolution is to start in Russia, it will begin with Tatarstan,’ Kazan historian says

- Tatarstan’s efforts to help Gagauz de-Russify outrage some in Moscow

- ‘Syrian war has cost Russia $2.2 billion already’ and other neglected Russian stories

- Profound contraction of ethnic Russians in former Soviet republics since 1989

- ‘Islam is changing Russia rapidly and profoundly,’ Polish writer says

- ‘Stop feeding Moscow!’ – slogan of next Russian revolution, St. Petersburg regionalist says

- Extending Moscow-Kazan power-sharing treaty will destroy Russia, Gorevoy says