Back to Soviet-style witchhunt

Last week, 59-y.o. Natalia Sharina, a Russian citizen and former head of the last Ukrainian government-funded institution in Russia, was found guilty of keeping “extremist” books in the library, as well as of alleged financial abuse. The trial, which Amnesty International called “the travesty of justice,” ended with a 4-year suspended prison sentence for her, after the over 1.5 years she spent under strict house arrest. The work of the library itself was cut off in the fall of 2015, and its 52,000 book collection is said to be transferred to another institution.

According to the judgment, Sharina was “inciting ethnic hatred” via the circulation of books among the readers. The court paid attention neither to the testimonies of the library staff who said they had seen a number of supposedly “extremist” books being planted by Russian law enforcers nor to the conspicuous fact of absence of library stamps on their pages. As for the rest, Sharina stressed in her last word before the verdict, “nobody gave a library director the right, moreover the responsibility, to censor legally published books.”

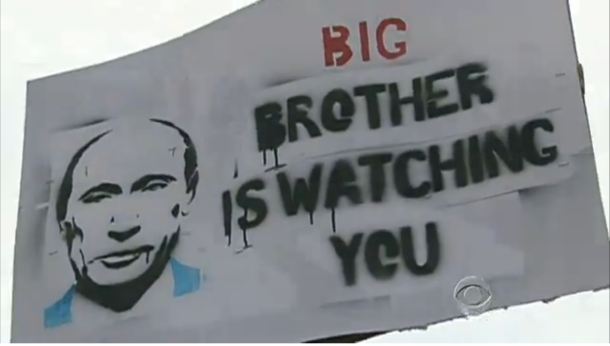

Control over the content of libraries, the removal of “wrong” literature and the punishment of librarians who did not keep up with the changing demands of censorship were typical features of Soviet cultural policy since the establishment of the Bolshevik regime a hundred years ago.

The aggressive actions of the USSR against its neighbors were among the locomotives of such “library purges.” In 1968, when the Kremlin sent tanks to suppress the political reforms in Czechoslovakia, Soviet libraries were instructed to remove quite a lot of books about this country. Among them were, for example, Soviet publications on the history of the Czechoslovak Communist Party and the liberation of Czechoslovakia from the Nazis during the Second World War. What was seen as harmless before, suddenly became frightening and unsuitable.

During its today’s intervention in Ukraine, like in 1968, the Kremlin leadership proved to be quite productive in fabricating enemies both among people and books. In the case of the director of the Ukrainian Literature Library, a remarkable feature is that the investigation, and then the court, relied on the allegedly scientific substantiation of the “extremist” content of the books in question. A look at the conclusions of the examination presented to the court provides a vivid picture of how linguistics has become an instrument of political persecution in modern Russia.

Professor for prosecution against dangerous words

In April 2016, the Institute for Linguistic Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences submitted to the Russian Investigative Committee the results of content analysis of two dozen books that were reportedly held in the Ukrainian Literature Library and defined as suspicious by the detective. The expert, elderly Professor Yevgeny Tarasov, head of the Institute’s Department of Psycholinguistics and editor-in-chief of the journal Questions of Psycholinguistics, sweepingly concluded that all the books but one incited hatred in connection with every possible feature one could spot in the legal definition of extremist activity: “sex, race, ethnicity, language, origin, attitude to religion, as well as belonging to a certain social group.”

The expert asserts that his findings are based on the state-of-art of the contemporary Ukrainian studies in Russia. However, this claim is false. The only publication Tarasov tries to pass off as the one reflecting the achievements in the field is entitled The Banderization of Ukraine: The Main Threat to Russia. This overtly propagandist book was published in Moscow back in 2008 and predicted a future conflict between “Nazi” Ukraine and Russia. Tarasov erroneously refers to it as a collection of research papers.

According to his statement, which would have fit well in the Stalin- or Brezhnev-time literature exposing the so-called “bourgeois falsifiers of history,” the books from the Ukrainian Literature Library have a “sharp anti-Soviet orientation.”

Those include, in particular, a book about the mass famine of 1947—48 in Soviet Ukraine. The expert is particularly indignant at the fact that the book describes the Stalinist state as an empire. This single word, he argues, can spur interethnic hatred because it implies “a negative appraisal of Soviet power” by definition. Tarasov is either not aware of the influential books on the interwar USSR as an affirmative action empire and the empire of nations, which are stored on the shelves of leading public and university libraries of Russia, or was compelled to forget about them by Russian law enforcement. In his report, he also denounces the “extremist” collocations like Moscow’s totalitarianism and Bolshevik terror in the books Sharina was said to be in charge of, because they also disparage the communist state.

If the expert were more cognizant of literature on Soviet history, the number of targets of his examination among librarians—and perhaps authors, publishers, editors, translators, reviewers, and ordinary readers alike—could amount to thousands. Among them (in absentia) there could be, for instance, Berkeley historian Yuri Slezkine, whose famous metaphor of “The USSR as a Communal Apartment” is also able to awaken palpable negative associations in the post-Soviet mind. However, it seems fairly possible that Professor Slezkine has been fortunate not to have Professor Tarasov among his readers.

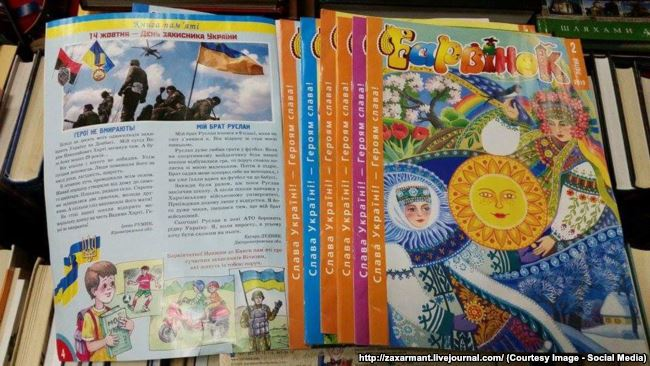

Children’s magazine on the black list

In 2014, the Russian State Duma introduced into the Criminal Code two major changes to suppress freedom of speech regarding the Kremlin’s aggressive actions in the past and present. Firstly, it outlawed any public statement on the illegal nature of the 2014 annexation of Crimea as a call for the “infringement of Russia’s territorial integrity.” This later allowed to imprison the Russian activists Rafis Kashapov and Andrey Bubeyev and put on trial the Ukrainian journalist Mykola Semena and Crimean Tatar leader Ilmi Umerov, who all said Crimea is a part of Ukraine under international law.

Secondly, the Duma approved penalties for disseminating “false information” regarding the Soviet policy during World War II. As the judicial precedent showed next year, the Russian court interpreted this norm as a ban on writing on the alliance between the Stalinist USSR and Nazi Germany in 1939—40 and its tragic consequences for Central East Europe.

The judgment in the Sharina case based on Tarasov’s examination goes a step further, extending the area of censored historical interpretation beyond the WWII period. Denying the space for discussion, the expert report pretends to make “extremist” every mentioning of the Soviet occupation of Ukraine, Georgia and other nations as one serving to “incite interethnic discord.”

At the same time, the expert is particularly concerned about the denial of the crimes committed by the Putin regime. In the most curious part of his “analysis,” the expert attacks the children’s magazine Barvinok for telling young readers about Russia’s ongoing war on Ukraine, which, he claims, “does not correspond to reality.”

Read also: War with Ukraine reveals hypocrisy of Russian intellectuals

Criticism of Stalin means offense at Putin

It is indicative that the report treats any criticism of Soviet authorities, starting from 1917, as hostile to Russians and present-day Russia. It appears that for Tarasov, nearly everything “anti-Soviet” is a priori “anti-Russian.” In the 1940s and 50s, he emphatically notes, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army fought against Soviet Russia. He offers no comment about why this fight took place far from Russia, in the territory of West Ukraine annexed by Stalin in 1939.

The testimony of the expert to the investigator contains a very simple and strikingly barefaced explanation of why criticism of the communist rule should not be tolerated. The books in question, according to Tarasov (and the court following him), “have signs of extremism since [...] they provide a sharp negative description of the activities of the Soviet government, whose heir is today’s government of the Russian Federation.” In other words, anyone who says Lenin or Stalin or Brezhnev did wrong (what about Khrushchev “handing over” Crimea to Ukraine in 1954 or Gorbachev starting the perestroika in 1985?) thereby slanders Putin.

It is interesting to compare this logic of distilling historical memory with the statements of present Russian leaders about the Soviet regime. The prime minister and former president Medvedev is known for his remarks that the revival of Stalinism is inadmissible and that Stalin’s crimes should be neither forgotten nor forgiven. In early 2016, President Putin personally accused Vladimir Lenin of national betrayal and laying down an “atomic bomb” under the greater Russia. Does it mean that keeping those speeches by Putin and Medvedev in printed or electronic form makes one prone to prosecution for Russophobia and “inciting ethnic hatred”?

The implication of the “expert conclusion” and verdict in the Sharina case is as much simple as perverse: that any idea of Ukraine’s existence independently of Russia is “chauvinistic,” “fascist,” and subject to eradication. The fate of the library and the librarian represent a regrettable but iconic example of how the repressive policy has triumphed over language, history, and the principles of academic ethics.

Read also:

- Russian protest spreads to more than 150 cities

- In fighting Russia, Ukraine must not become like it, Ukrainian churchman says

- Every meek pointless protest in Russia is a nail in the regime’s coffin

- Moscow worried Russian ‘ceasing to be language of majority’ in Ukraine, Shchetkina says

- “Moscow’s appropriation of Ukrainian history not limited to Queen Anna Yaroslavna” and other neglected Russian stories

- Matviyenko edges toward acknowledgement of Putin’s aggression against Ukraine

- Russia, known for Potemkin villages, is now ‘a garden of fig leaves,’ Yerofeyev says

- Are there “independent” media in Russia and why would Putin need them?

- Russia and its authoritarian friends lag increasingly behind its free enemies, Illarionov says

- The worst Russophobes in the world are in the Kremlin, Kornyev says