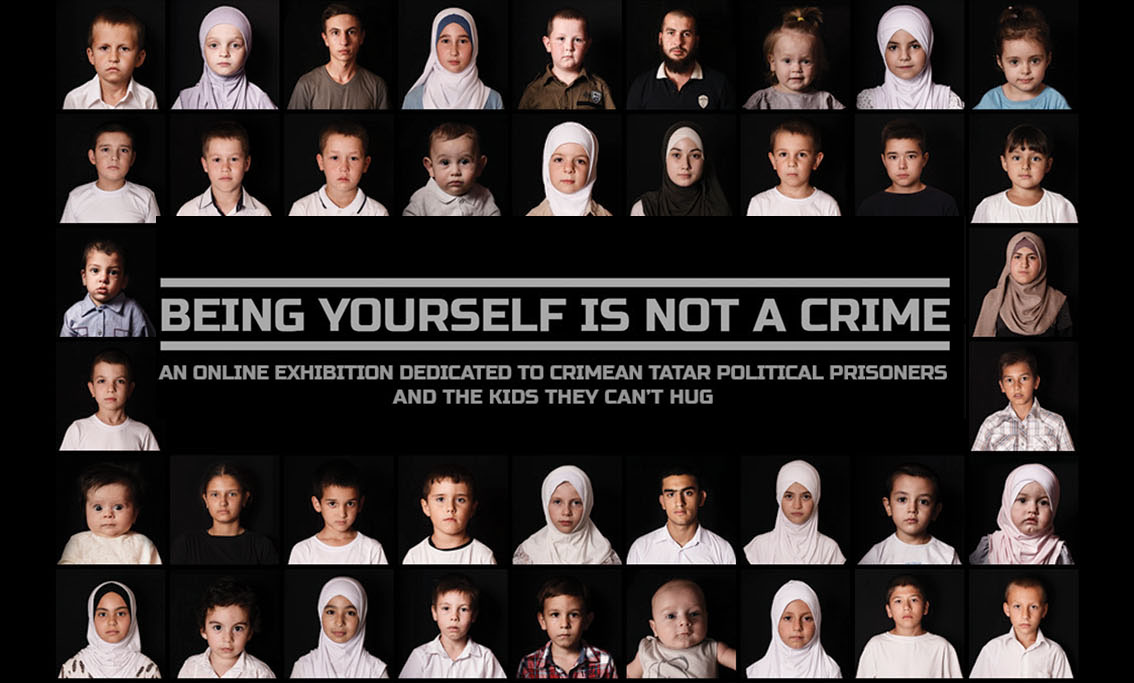

Together with adults, they experience searches, arrests of relatives, and trials, where they come to see their dads or grandfathers. They are supported by the organization Bizim Balalar, which cares for the 66 suddenly grown-up kids. With time passing, the number of such children in Crimea is only increasing.

Summer of 2016, a psychiatric clinic in Simferopol. A regime object, guards are on duty at the entrance, and relatives can meet only briefly and according to the schedule. In the wards, together with patients, there are people who undergo a psychiatric examination of their sanity. A little girl approaches the lattice of the door, behind which stands her grandfather, Ilmi Umerov. She thrusts her thin arms through the bars, hugs him and kisses his hand, where she manages to reach. “Why are you silent?”, Aunt Ayshe asks her. “Say something.” But the girl is just smiling, keeping silent, hugging her grandfather, and is not leaving the grate until the time of the meeting ends.

Read more: Who is Ilmi Umerov, the Crimean Tatar Russia so fears?

Ilmi Umerov, a former head of the Bakhchysarai District and deputy chairman of the Crimean Tatar Mejlis, which is banned in Russia, is accused of calling for separatism. The pretext is his interview with the Crimean Tatar ATR TV channel, where he talked about the annexation of Crimea by Russia and the need for international pressure to return the peninsula to Ukraine.

“In fact, I want to restore the territorial integrity of both Russia and Ukraine,” Umerov said in court. “I do not recognize the ‘referendum’ [held on 16 March 2014, after Russian military occupied Crimea], which was conducted in violation of all international norms. I have no claims to the borders of Russia established in 1991. And I consider what happened in 2014 a violation of international law and, most importantly, of the laws of Ukraine, where the territory of Crimea was torn away from.”

Read more: Umerov case highlights why Crimean Anschluss a threat to Russians, Portnikov says

The court sent Umerov to a psychiatric clinic for compulsory examination, where he spent three weeks. His relatives visited him several times a day to bring food. He refused the meals provided by the clinic, suspecting that psychotropic drugs could have been slipped into them. His granddaughters were coming to the hospital together with the adults.

After the forced examination, having repaired his health damaged in the clinic, Umerov received guests who gathered in his house for Dua—the collective prayer. For Crimean Muslims, Dua is virtually the only way to get together and pray for the fate of Crimean Tatars and pro-Ukrainian activists arrested or missed in Crimea. A row of benches was set in the yard of his house in Bakhchysarai, and a Crimean Tatar flag hung on the wall. One of Umerov’s little granddaughters met every guest at the entrance, offered them water and juice and, when the prayer began, sat on the female half with all the prayers.

“Do you love your house?”, the guests ask Umerov. Next to him, on the lawn, which has an insect-proof net above so that children can play there, his granddaughters run among fir trees. “Yes, my wife designed this house, and we love it very much,” he answers. “Does your family feel safe?” The host is silent for a moment and then replies: “No. Nobody in Crimea can feel safe.”

On 31 May 2017, a district court in Simferopol started to consider the case of Umerov. The maximum term under Article 280.1 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation (public calls for separatism) is five years in jail. The lawyer Nikolai Polozov, who was taken out of the Umerov case by the FSB investigation and shifted to the status of a witness, does not doubt that the verdict will be “guilty” but hopes the term will be conditional. The first meeting was closed, and Umerov’s granddaughters were waiting for their grandpa at home. He is under an undertaking not to leave the place and so he came home after the trial. Many other children of the Crimean Tatars are less lucky.

Read more: Escalating repressions in occupied Crimea: Russia detained key defense attorney

Nineteen people have been charged within the large case of the Islamic organization Hizb ut-Tahrir banned in Russia. For the most part, they are traditional Muslims with big families, which after their arrests were left without the breadwinners. The first mass arrests took place in Sevastopol District in January 2015. Then the searches and arrests were conducted in Yalta, Alushta, Bakhchysarai, and Simferopol.

One of those detained in February 2016 was the Crimean human rights activist Emir Usein Kuku. According to his words, the FSB tried to recruit him but he refused to cooperate, and after that, they came to him with a search. Early on the morning of February 11, the “law enforcers” broke the door of Kuku’s house, threw him on the floor and searched the place. His little son Bekir and daughter Safiye were watching the scene. Later they described what had happened.

“Some ‘black people’ came in, their eyes were hardly visible. One of them was carrying a huge stick similar to a crowbar, and others had a kind of strange machine guns,” Bekir Kuku recalled on his ninth birthday. “Had there been a dad with us, we would have celebrated a small birthday and bought presents. But he is sitting there, in a remand jail, among fleas and ticks. He would like so much to return and see how his son turns nine.”

A few months after the arrest of Emir Usein Kuku, a man came to Bekir’s school. He waited for the boy after lessons, stopped him and told that his father was “a bad guy and would spend very long time in jail if he did not agree to cooperate.” Subsequently, it turned out that the man acted at the instruction of the Russian FSB officer, turncoat from Ukraine’s Security Service, Aleksandr Kompaneytsev.

Upon this, Kuku’s family and lawyer Alexander Popkov filed a complaint to the prosecutor’s office and FSB. However, the “law enforcers” reacted in a very peculiar way, accusing Emir Usein Kuku, who was in jail, of not fulfilling his parental responsibilities for “letting an unidentified man harass the child.” The prosecutor’s office initiated the inspection, and the juvenile inspector demanded that the mother bring children to give explanations against their father. When they refused to come, the inspector began to watch for the kids at school to catch them without the mother.

Fortunately, human rights defenders interceded for the family, and Amnesty International demanded that the persecution of Kuku and his children be stopped. After that, nobody tried to question Bekir but nothing has been known yet about the results of the inspection.

“Children are afraid to go to school, and adults fear that masked people with guns will come for children,” says the lawyer Alexander Popkov.

Bekir, like other children of arrested Crimean Muslims and activists, is now well aware of the stages of the trial and knows what a “measure of restraint” and “appeal” are. Such children attend each hearing to see their fathers: families are not allowed to visit them in remand jail. They are often even denied to enter the courtroom on the pretext that “the image of the father behind bars can affect the psyche of the child.” Together with adults, they stand in the corridors to see their fathers escorted under guard before and after hearings. Sometimes they get a chance to touch their hands. All these children have witnessed searches, and detentions also took place before their eyes.

“For our kids, childhood ended on 11 February [2016], just in a few minutes,” says the wife of another arrested, Muslim Aliev. Next to her are four children, including the teenager Ilyas, who, after his father was arrested, substituted him as the eldest man in the family. The other families also usually have three or four children. In the family of Enver Mamutov, who was arrested in Bakhchysarai, there are seven. His youngest daughter was two months old in the time of his arrest. Her mother brought her in court to show her father from behind the bars when the prolongation of the arrest was considered.

Read more: Imaginary “terrorists” with no terror acts: Russia’s collective punishment of Crimean Muslims

The daughter of Rustem Vaitov (who has been already convicted), Safiye was born after her dad’s arrest, like the daughter of Teymur Abdullaev born nine days after the search and detention. In total, about a hundred Crimean children have left without fathers since 2014, of which 66 are monthly supplied with aid by the organization Bizim Balalar (“Our Children”).

Bizim Balalar was established in May 2016, following the mass arrests in Bakhchysarai, where four families were deprived their fathers. The initiative was put forward by the Crimean journalist Lilya Budzhurova, and many people supported it. The organization is not registered by the Russian Ministry of Justice, in order not to fall under the strict Russian legislation on public organizations, and operates as an association.

Every month, Budzhurova and Elzara Islyamova meet with the wives of arrested Crimean Muslims and activists and hand them over the aid for the children. Unlike the organization Crimean Solidarity, which was created to help Crimean political prisoners and their families, Bizim Balalar purposefully emphasizes that it has nothing to do with politics and deals only with the needs of the kids. For each child, it allocates 5,000 rubles monthly and 12,000 additionally by the start of the academic year.

The organization invites children’s psychologists for classes. They help not only the kids of arrested Crimean Tatars but also, for example, the children of the convicted filmmaker Oleg Sentsov and of Reshat Ametov, an activist who was the first to be murdered for picketing against the annexation of Crimea in 2014. The number of children supported by Bizim Balalar is growing over time.

The children of Crimean political prisoners, mostly Crimean Tatars who are persecuted for pro-Ukrainian position or on religious grounds, know how searches and arrests look like. They come together with adults to court hearings and pray for their fathers at Dua like everyone else.

A few months ago, Crimean courts began to conduct the trials in the Hizb ut-Tahrir case in closed sessions, hence nobody but lawyers is allowed in the room. Children and adults gather near the courthouse but now they cannot even look at their arrested relatives for a moment. The kids face the same problems as adults: weekly searches of activists, trials, and harassment. For them, Crimean childhood has proved to be very short.

Related:

- Children in Donbas taught to avoid mines

- Indoctrination campaign for kids reveals identity crisis of Kremlin’s proxy “republics” in Donbas

- Why is the Kremlin taking Ukrainian political hostages? | VIDEO

- Russia methodically destroys and removes cultural treasures from occupied Crimea

- Ukraine moves forward with issue of political hostages held by Russia

- Moscow deaf to 3 years of international outcry to free imprisoned Ukrainian filmmaker

- Who is Zeytullaev, the Crimean Tatar Russia just sentenced to 12 years without a crime?

- Putin doesn’t want Russians to continue focusing on Crimea, Goryunova says