Russia and Ukraine hold the world’s largest documentary collections of Communist secret services that ceased to exist in the early 1990s but once had been extremely powerful and disposed the future of millions. These documents cover the major part of the 20th-century history, including economic, social, and cultural life, various domains of domestic policy and international relations.

The dissolution of the USSR in 1991 gave rise to the expectations that the new Russia would open these files to the world and its own citizens. And the veil indeed began to lift but stopped halfway. The creeping revenge of the unreformed state security machine pulled it back down, which means that myriads of secrets remain concealed from the public domain.

The radical liberalization of access to ex-KGB archives in post-Maidan Ukraine, like other democratic changes, may be seen as belated, but its role can hardly be overestimated. It allows many thousands of people to find out what they did not know about their relatives who had been repressed. It demonstrates that the crimes of political regimes and the names of their perpetrators sooner or later come to light. And last but not least, it is a sign that the Ukrainian state is starting to trust the civic society.

A colleague of the Russian cultural historian Vitaly Shentalinsky, who studied the files of the writers repressed during the Stalin era in the former KGB archives, compared him to Dante, who, in The Divine Comedy, descended to the inferno and came back to the human world.

In the past two years, both Ukrainians and foreigners have received a unique opportunity to study the papers of Soviet security agencies preserved in Ukrainian archives even without leaving homeIt was a settlement for the former gulag prisoners in North Russia where the young people from West Ukraine fell in love.

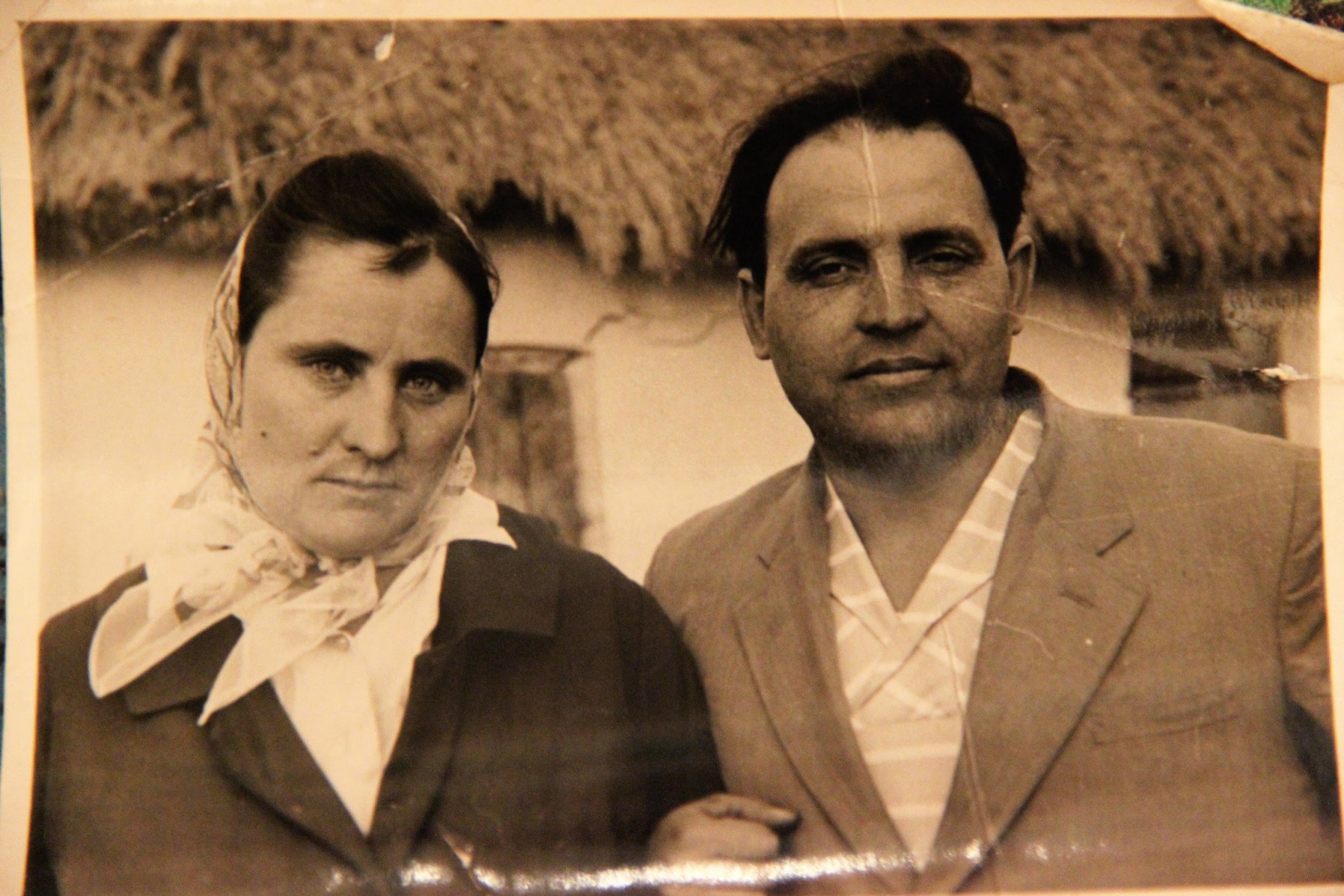

. My friend, the artist and civic activist Yaroslav Synytsya has used this chance to find out how the KGB predecessor, NKVD, had arrested, charged, and interrogated his grandparents in the 1940s—before sending them to serve long years in a prison camp.

Yaroslav’s grandparents did not readily talk about that time: the burden of suffering was too heavy. What they did recall, nonetheless, would be enough for an adventure romance plot. It was a settlement for the former gulag prisoners in North Russia where they, the young people from West Ukraine, met and fell in love.

Read also: The story of Anna Popovych: love, war, death, gulag and freedom

Everything Yaroslav needed in order to learn more in 2017 was to send an online request to the main archives of Ukraine’s Security Service (SBU) at the email [email protected]. Just in a few days, he received the scanned copies of the relevant documents found in the regional SBU repositories. He knows now that his Grandpa Dmytro had been sentenced to ten years in a Soviet gulag for unarmed involvement in one operation of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army during WWII, and Grandma Mariya had got 25 years for feeding the insurgents milk and bread and holding their anti-communist leaflets.

Yaroslav is planning to continue his search and gather as many pieces of his family mosaic against the backdrop of the brutal 20th century as possible.

And the prospects of such a search look promising. On 9 April 2015, the Ukrainian parliament adopted the law “On the Access to the Archives of the Repressive Organs of the Communist Totalitarian Regime of 1917—1991.” Based on this law, the SBU opened its archives to the wider public for the second time in the history of independent Ukraine.

Read also: Summary of Ukraine’s four new decommunization bills

The first attempt made in 2007 lacked strong a legal framework and was subsequently canceled under President Viktor Yanukovych. Fortunately for researchers, even Yanukovych did not accede to the agreement with Russia, Belarus, Armenia, and Kazakhstan that required the consent of all other parties to declassify any secret archival document.

Now, according to the 2015 law, the Soviet-time records of a number of security agencies (including the Interior Ministry, foreign intelligence, prosecutor’s office, border and penitentiary services) in the Ukrainian capital and regions is open unconditionally along with the SBU archives. If all those materials were put in a row, it would stretch for 150 kilometers

. Eventually, all the files concerning the repressive policy and practice are to be transferred to a new single public repository.

Open access is of great importance for the Ukrainian society given that the country was particularly hit by the Soviet repressions, a combination of bloody retribution for potent resistance movements with a paranoid witch-hunt. Now the living victims of the persecution and their relatives are provided welcoming conditions to uncover the truth that was hidden for decades.

Read also: Remembering Soviet atrocities: Solovki and Sandarmokh

One film producer had never seen the photo of his great-grandfather until he came to the SBU archives with a professional purpose of making a documentary. Occasionally, visitors can even handle personal belongings of the arrested, which had been stored together with interrogation reports, such as pocketbooks, handkerchiefs, or hats. A box containing the case file of the Ukrainian dissident Stepan Khmara preserved his raincoat and, strangely, a bucket.

“Sometimes I personally take part in processing the request as a consultant,” says Roman Podkur, an expert in the history of Soviet special services. “People want to find out how their grandfathers, great-grandfathers, or fathers conducted themselves during the interrogation, and whether they were able not to bow down.”

In a year since the respective law was adopted, the number of citizen requests sent to the main SBU archives increased by 138%, while the number of its foreign visitors in 2016 doubled compared to the previous year.

Under the new law, the Ukrainian government takes responsibility to systematically digitize the documents of the repressive bodies, as well as to provide electronic copies on demand. Also, visitors of the archives can freely copy those documents using their own cameras or portable scanners. All this makes Ukrainian archives a Klondike for researchers of Soviet history from around the world. Such a liberal mode of access to the huge documentary collections of the communist secret services is quite unusual even compared to EU standards.

“It is simply a pleasure to work in the Ukrainian archives,” enthusiastically says the Czech historian Štěpán Černoušek, chairman of the organization Gulag.cz, which studies the fates of Czechoslovak victims of the Soviet repressive system. “While in Russia, everything is ‘top secret,’” he adds, “in Ukraine, everything is freely available.”

One may wonder why the access to the similar and sometimes identical documents of a nonexistent state and its institutions is so different in Ukraine and Russia. To understand this, it is worth looking into the use the Soviet special agencies made of archival records, and the latter’s afterlife in the post-Soviet era.

In the USSR, archives both accumulated the records of state terror and served as a tool for its implementation. Investigators studied them as a source of carefully collected personal information that could once ruin the life of a potential victim. Since 1938, all the Soviet state archival repositories were subordinated to the punitive agency, NKVD (later MVD).

Based on the files from the state archives, 108,694 “enemies of the people” were “exposed” in 1939. Next year, when the NKVD thoroughly combed the archives of annexed West Ukraine, West Belarus, Bessarabia, and the Baltic states, the number of those “exposed” was almost thirteen times as many (nearly 1.4 million). The archives of the Communist Party formed a separate system which was also instrumental for political purges and persecution.

In 1991, the Soviet empire was mortally ill, and its secrecy stamps were likely to become null and void. On 24 August, after the coup of the communist orthodoxy failed in Moscow and the day when Ukraine declared independence, Russian President Boris Yeltsin issued two decrees on the transfer of CPSU (Communist Party) and KGB archives to the state (meaning non-USSR, Russian) repositories.

Yeltsin was himself the son of a repressed peasant: in 1934, when he was only three, his father was sentenced to 3 years in labor camps for “anti-Soviet agitation.” Only when Yeltsin became president did he get a chance to page his father’s case file. In 1991, Yeltsin was also handed the recent transcripts of KGB tapping of his own phone—with Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev’s remarks on the margins.

Read the next part: Difficult choice for Ukraine as identities of KGB agents finally come to light

Read also:

- 80 years ago, Stalin’s NKVD began to arrest and shoot the deaf and dumb

- Historical documents detailing Vistula operation to deport 150,000 Polish Ukrainians now online

- The Soviet foundations of Russia’s Great Patriotic War myth

- Andrey Zubov: Russia will one day be a normal country

- Ukraine remembers 100 years of revolution

- Munich and the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact revisited, Part 1: The interwar prelude, Part 2: Hitler’s Anschluss, Part 3: The way to European catastrophe

- Georgia a victim not just of communism but also of Soviet occupation, memorialization reaffirms

- On 73rd anniversary of deportation, Chechnya and Ingushetia divide on Stalin and his crimes