Two new commentaries, one about Russia’s refusal to enter into any larger political structure in 1991 if Ukraine refused to take part and a second about the propensity of Ukrainians to view Russians as a fraternal people even now after Moscow invaded their country and seized Crimea highlight the highly fraught ties between the two peoples.

In a commentary on Kasparov.ru, Russian analyst Andrey Illarionov argues that

And that outcome was not driven by the results of the December 1, 1991, Ukrainian referendum but “at a minimum” by decisions taken a week earlier. Boris Yeltsin, for example, said on November 25th that as long as Ukraine doesn't sign a political treaty, “Russia will not put its signature to it either.”

That conclusion is confirmed, Illarionov suggests, not only by Ukrainian leader Leonid Kravchuk’s statement that Yeltsin understood that “’without Ukraine … there will not be a Union’” but also by Mikhail Gorbachev’s remark that he couldn't imagine “a Union without Ukraine.”

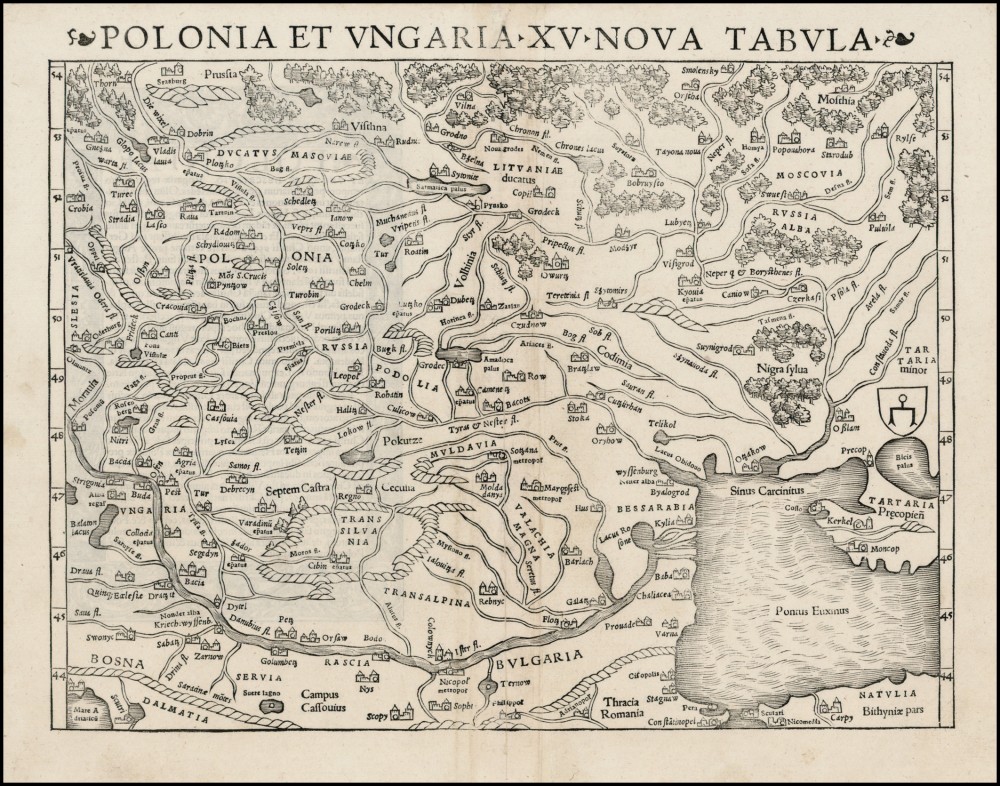

At the end of November 1991, seven republics were ready to sign a treaty on the formation of a Union of Sovereign States; but Ukraine was not among them and so Russia wasn’t either and nothing came of this last attempt to form at least a confederal relationship among the union republics.

“Why did the Russian leadership reject the participation of Russia in [such a state formation] without Ukraine?” the Moscow commentator says. A recent interview given by Gennady Burbulis

to Radio Liberty came close when he said that a Union without Ukraine was “completely impermissible.”

Unfortunately, before Yeltsin’s chief ideologist could complete his thought on this subject, he was interrupted by his interviewer and did not return to it, Illarionov says. But while Burbulis did not have the chance to speak to this point and Illarionov doesn't either, there are at least three obvious reasons:

- First, a union of any kind in which Russia was dominant but Ukraine was outside would be one in which demographically the Slavs would not be much better off than they were in the USSR at the end and the Muslims would be a much larger share. That would mean that Russia would be forced to turn even more away from Europe than otherwise.

- Second, a union without Ukraine would undermine Russian views about the origin of the Russian state and culture given the obsession with the baptism of Kievan Rus as the supposed beginning of the Russian state and would almost certainly, as indeed it has, lead to efforts by Moscow to “retake” Ukraine.

- And third, and again the echoes of this are still being heard, the existence of an independent Slavic country in the form of Ukraine would exacerbate centrifugal forces within Russia, sparking more regionalism and even separatism among those the Kremlin defines as ethnic Russians but who view themselves as distinct.

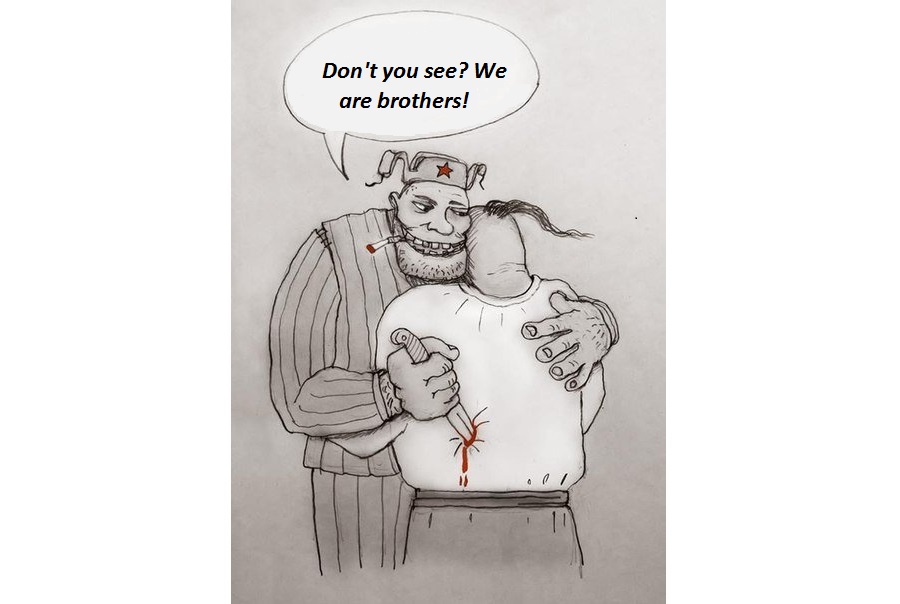

The second commentary is offered by Taras Klochko in Kyiv’s Delovaya stolitsa newspaper concerning recent poll results showing that just over half of Ukrainians still view Russians as “a fraternal people.”

One of the most beloved themes of Soviet propagandists was the notion that Russians and Ukrainians were “fraternal peoples,” an idea that even “military aggression, occupation of part of the country, and other ‘delights’ of the Russian world” have not succeeded in driving out of the heads of Ukrainians.

According to the latest Razumkov Center

poll:

- 51.1 percent of Ukrainians still consider the Russians a fraternal people,

- 33.8 percent don’t,

- and another 15.2 percent either can’t or won’t say.

At one level, these results are shocking given what Russia has done to Ukraine over the last three years.

But at another, Klochko says, “there is nothing particularly surprising in such results.” A poll taken earlier this year found that:

- 67 percent of Ukrainians had a good or very good attitude toward Russians,

- only 21.5 percent had a bad or very bad one, even though they had an overwhelmingly negative attitude toward Putin, with only eight percent viewing him positively.

One reason that idea of “fraternal peoples” has survived is because it can be interpreted to mean so many things; but that doesn’t mean that its survival in the heads of Ukrainians is not a matter of concern for those who care about the survival and flourishing of the Ukrainian nation and state.

A major reason for that conclusion, Klochko suggests, is that that the notion that there is a bad Putin but good Russians, “absolutely mirrors the thesis actively spread now by Russian propaganda about the bad ‘Kyiv Banderite junta’ and the on the whole not bad fraternal Ukrainians,” an idea Moscow uses to weaken Ukrainian support for the Ukrainian state.

The Ukrainian government and the Ukrainian media should be countering this every day, Klochko says. But “unfortunately, even patriotic television channels concentrate more on domestic scandals” than on this, something for which they may ultimately suffer, if this attitude is allowed to continue.

Related:

- Ukrainians' strong horizontal ties a serious weakness when it comes to their attitudes about Russians, Shchetkina says

- Why only 48% of Ukrainians blame Moscow alone for war in the Donbas?

- Russian journalist Valeriy Solovey: What Russians don't like about Ukrainians

- Why Americans are "stupid," according to Russians