Over the last year the Holodomor has garnered much needed additional publicity, in part due to the current situation in Ukraine but in the West discussion of it is still often met howith the look of confused faces and a great deal of general ignorance persists. But now the famine of 1932-33 is set to receive some extra publicity in the form of “Bitter Harvest”, a movie starring among others Max Irons, Samantha Barks and Barry Pepper. It tales the tale of Yuri, a native of Smila whose initial passion for being more a lover than than a fighter conflicts with his cossack heritage, but his would be love relationship with Natalka, a child sweetheart as well as relationships with the rest of his family are torn asunder by the events that unfurl around them.

Smila may have been a village then but it has since grown into a small city which alongside Uman and Cherkassy itself is one of the major population centers of what is now the Cherkassy Oblast. Few films have ever been perfect in depicting historical events but Bitter Harvest despite being a drama looks far more promising to reflect more the realities of the Holodomor than certainly the propaganda photos designed to mislead that Demchenko below was proud to pose for. Judging by the official film website, thought and research was evidently put into the production of the film and now we have the 1st official trailer out. Obviously one can only draw so much from a trailer, but this post will examine some of its apparent themes and how they depict the history of the Holodomor as it was.

“I was born in a country where anything was possible … we celebrated simple freedoms… to live and to love” - Yuri in “Bitter Harvest”.

There is a theme in Hollywood films of depicting backstories as blissful innocence or even a child-like sense of naivety which gets disrupted as the story plunges the characters and the world around them into darkness before the characters get dragged back up into the ending. It remains to be seen how much or if indeed Bitter Harvest follows this format.

But as things were, Ukraine’s pre-Holodomor state was not a golden era. It’s actually also worth understanding that Soviet ambitions over Ukraine began immediately after the October Revolution.

Read more: Dancing with Stalin. The Holodomor genocide famine in Ukraine

Grain, Grain, Grain to feed Soviet Russia

On 15 January 1918, Lenin sent a telegram to his associates calling for “Grain, Grain, Grain” to be forcibly requisitioned from Ukraine to feed Soviet Russia [1]. By 1921 after the concept of an independent Ukrainian state had been crushed by Soviet military might and partitioned between the USSR and Poland, this ambition to control Ukrainian Grain led to the 1st Soviet famine to impact Ukraine which claimed the lives of 1-1.5 million Ukrainians.

Yet discontent persisted particularly amongst Ukrainian peasants who had not given up upon the concept of preserving Ukrainian culture or the thoughts of independence. Subsequent Soviet policies such as the “New Economic Policy” (NEP) and “Ukrainization” were based on attempts to consolidate Soviet rule by appeal to the peasants but by 1928 this had been overturned by Stalin.

Officially the justification for doing so was that the NEP policies were widening a gap between the USSR and the Capitalist West and in this we find Stalin’s well known remark that "We are fifty or a hundred years behind the advanced countries. We must make good this distance in ten years. Either we do it, or they crush us."

But ideologically, the reverse of the NEP and “Ukrainization” was to bring the USSR and by extension the Ukrainian SSR closer to Stalin’s own wishes based on Marxist-Leninist ideology. The NEP had allowed a modicum of agricultural private enterprise and as a result hunger in the mid-1920s didn’t become so much of an issue as being forced to conform to state whims. But Stalin’s policy reversal changed that. Lenin’s policy of forced requisitions returned and with it those farmers suspected of having profited from the NEP were punished as “Kulaks.”

Related: See which countries recognize Ukraine’s Holodomor famine as genocide on an interactive map

With the forced collapse of the grain market, famine was quick to follow. The cry “у селян хліба немає” (“The peasants have no grain”) had been noted around Cherkasy as well as elsewhere by February 1929 [2]. By 1930 soviet repressive policy was met by a large wave of protests of which the countryside around Cherkasy and Uman formed a major of epicentre of anti-soviet resistance. Though not every Ukrainian was a participant to resisting soviet rule but to Stalin this mattered not. In the long run the ever increasingly repressive policies that characterised the Holodomor were grossly disproportionate to whatever real or alleged crimes Ukrainians were supposed to have committed.

“Ukraine must be taught to bow to our will … without its vast harvests of grain Russia cannot exist … take all their food.” - Stalin in “Bitter Harvest”.

On 6 July 1932, during the “Third All-Union Conference of the Communist Party of Ukraine”, Stanislaw Kosior, prominent Soviet politician and leader of the communist party of Ukraine until 1938 addressed his comrades about the situation around Uman:

“Comrades, many regard the extensive grain procurement plans as a major cause of the current difficulties in Ukraine ... There have been a fair number of anti-party elements who have obtained party membership in Ukraine. They believe that we plunder Ukraine in favour of Moscow. They reflect kulak theories and sentiments and Petlyurite theories … It is no accident that in the Uman raion the number of mistakes was the highest. Those who are familiar with this area know that one can find the greatest number of Petlyurite and kulak elements, their agents, and counter-revolutionaries of various stripes. Our local party organisation is infected in those raions in which we have the most outrageous distortions of plans." [3]

On July 9, it was agreed by those present and acting on Stalin’s whims that the final resolution to the conference demanded that the Ukrainian SSR must procure 6.6 million tons of grain by the years end. It was in the mad pursuit of this target that the worst phase of the Holodomor was enacted through the winter of 1932-33 but even at this time the Ukrainians were already suffering under the auspices of hunger.

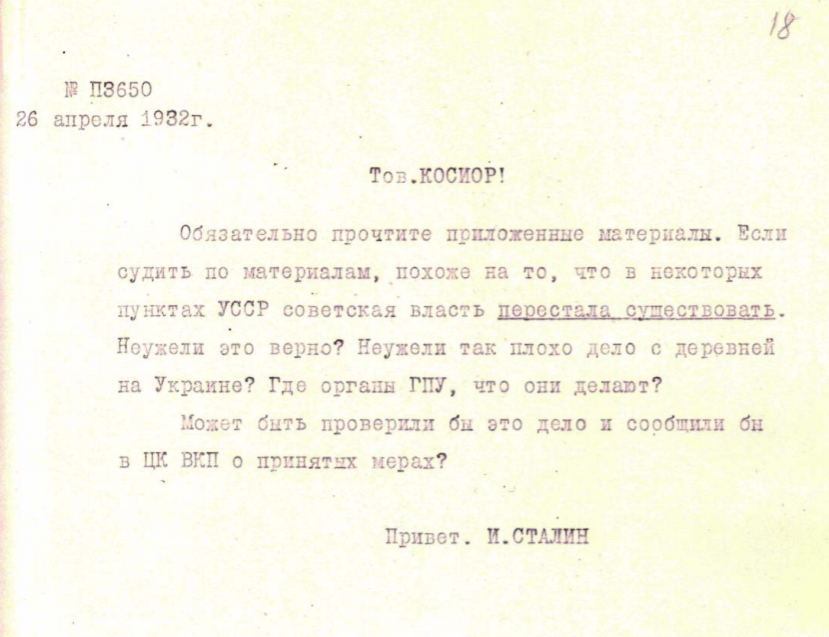

Earlier in the year on April 26 Stalin received a letter from Kosior written in minimalist tone reporting that there were only “isolated cases of starvation” including involving whole villages starving blaming “only the results of bungling on the local level and [party line] deviations, especially in regard of kolkhozes [collective farms].”

But Stalin’s reply was ecstatic; interpreting Kosior’s remark about “deviations” as Soviet authority no longer existing in certain parts of Ukraine Stalin rhetorically asked “Can this be true? Is the situation in villages in Ukraine this bad?” The alleged lack of Soviet control of the Ukrainian peoples as well as combatting what Stalin would later call “rotten elements” in Ukraine became the pretexts to his infamous telegram to Kaganovich on 11 August 1932 advising him to turn Ukraine into a lethal “fortress.”

Kosior’s April 26 letter is in the final analysis misleading in its information about the extent of famine in the Ukrainian SSR and Stalin’s rhetorical question was pre-empted by a tongue-in-cheek letter sent to Stalin by an Uman based Komsomol member wherein Stalin’s rule was likened to “bourgeois” serfdom rather than Soviet, and famine was blamed on quotas being too high as well as extensive searching for food in the pursuit of quotas by Soviet secret police.

The full extent of the famine around Uman was noted by Henryk Jankowski, head of the Polish consulate in Kyiv “I report …” he wrote in a report to Polish diplomats in Moscow dated 11 May 1932:

“[in] Uman each day there are cases of people being picked up from the street, having collapsed from feebleness and atrophy. The situation is supposedly worse in the countryside, where according to a reliable source, plundering and murder for food are a daily occurrence.” [5]

Reports such as this especially from the Polish diplomats who were in Ukraine at the time are very typical at describing the situation around them in general.

It is a common theme of Stalin apologetics to interpret his remarks about loss of control literally (and in essence blaming his victims). This denial is routinely extended to denial that there even was a famine, a propaganda line parroted by even the lower ranks of the NKVD at the time. “During my examination at the Smila prison,” eyewitness Marko Kruhly would later recall:

“I inadvertently mentioned the famine that raged in Ukraine in 1932-1933. When the NKVD agent heard the word “famine” he jumped from the chair, slapped my face hard and said: ‘What famine? We have no famine here, only state difficulties!’” [6]

“Who in the world will know?” - Stalin in Bitter Harvest.

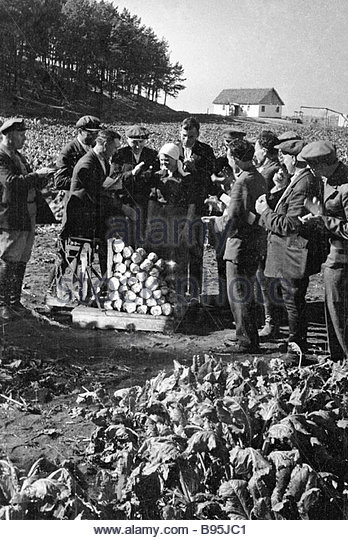

It is hard to underestimate how effective Soviet propaganda has been in covering up the realities of the famine. The sort of Ukraine that Stalin wanted you to see involved happy smiling collective workers bringing in record harvests and a Ukraine completely detached from reality. To this end Stalin allowed prominent western intellectuals to be given Potemkin Village tours and used New York Times Moscow correspondent Walter Duranty to parrot Soviet propaganda in exchange for him getting closer access. But Stalin promoted the myth of Ukraine being a workers paradise within the USSR also, and even allowed certain Ukrainians to become propaganda icons for the cause, and among the most iconic of these is Maria Demchenko. Born in a small village in the Horodyshchens'kyi district in 1912; by the early 1930s she had risen to become one of the leading figures in the agricultural wing of the “Stakhanovite movement” named in honor of a Donetsk coal miner who was reported to have vastly exceeded his production quotas. Demchenko was celebrated in soviet propaganda for exceeding her quota of beet production and was more than happy to pose for propaganda photos with her alleged crop. This propaganda photo was taken on 1 September 1933.

“I have seen people left to die … this is not a famine, this is Starvation.” - Yuri, in Bitter Harvest.

At its peak in early Spring 1933 an estimated 25-30,000 Ukrainians were perishing each day across the Ukrainian countryside. There is evidence to suggest that awareness of death on such a massive scale certainly existed. In one undated pamphlet distributed (most likely) in May 1933 calling for resistance around a village in Helm'yazivskoho we find these remarks.

“Today we live in the grip of the communist party who uses hunger to stifle the working peasants. The evidence is everyday in our country 16,000 die of hunger ... The communists are the death of Ukraine, several million people ... Villagers, let us oppose the Communist Party and organize a united front.”

Just 5 days before he called on Kaganovich to turn Ukraine into a “Fortress”, Stalin on August 7th 1932 enacted a piece of legislation commonly known as the “5 Ears of Grain Law” stating that any “misuse” of “collective” property be met with either shooting on the spot or 10 years imprisonment. As all property was now deemed to be in the hands of the state and with “misuse” loosely defined, even collecting just handfuls of grain was enough to have you punished by death. This law was also applied to children such as Fedir Krikun; born in the village of Klyuchnyky in 1923. At the age of 9 he recalled attempting to steal grain stalks from a nearby collective farm to where he lived. He was lucky to survive both the famine and a severe leg wound inflicted by an NKVD guard who shot at him. But the “5 Ears of Grain Law” was only one step in a set of policies enacted through the Autumn of 1932 which were deliberately designed to increase the level of repression.

“Ukraine must be taught to bow to our will … without its vast harvests of grain Russia cannot exist … take all their food.” - Stalin in Bitter Harvest.

“Close the borders. Keep them in.”

Arguably the most lethal repressive policy enacted through the Autumn of 1932 was the blacklist system. Any community caught in it was to be cut off from any food or supply from anywhere else. The blacklisted communities had no right to trade nor were they allowed to import any food to feed local populaces.

As a result, anyone caught within a Blacklist area was guaranteed death.

Officially the justification for the blacklist system was that it would put an end to any alleged "grain procurement sabotage organised by kulak & counterrevolutionary elements," with the added aim of breaking the "resistance of rural Communists", "sabotage leaders," and "liquidating passivity and indifference to saboteurs, which is incompatible with being Party member, and ensuring the faster pace and full and unconditional completion of the grain procurement plan."

In practice it also meant Blacklisted communities being swarmed with party loyalists and secret police tasked to find whatever meagre rations of food remained and punish anyone for hoarding it. Among the best accounts of the Holodomor in a Cherkassy village by someone who lived through it is Miron Dolot’s “Execution by Hunger”. Of the consequences of the Blacklist system, Dolot writes:

“Now it began to dawn on everyone why there wasn’t any food left in the village; why there weren’t any prospects of getting any more; why our expectation that the government would surely help us to avert starvation was naive and futile; why the Bread Procurement Commission still searched for “hidden” grain; and why the government strictly forbade us to look for means of existence elsewhere. It finally became clear to us that there was a conspiracy against us; that somebody wanted to annihilate us, not only as farmers but as a people—as Ukrainians. At this realization, our initial bewilderment was succeeded by panic. Nevertheless, our instinct for survival was stronger than any of the prohibitions. It dictated to those who were still physically able that they must do everything to save themselves and their families. The desperate attempts to find some means of existence in the neighboring cities continued. Many of the more able-bodied villagers ventured beyond the borders to distant parts of the Soviet Union, mainly to Russia, where, as we had heard, there was plenty of food. Others went south, since we had also heard that there, in the coal mines and factories of the Donets Basin, one could find work with regular pay and food rations. However, few of the brave adventurers who set out for these lands of plenty reached their destination. The roads to the large metropolitan centers were closed to them. The militia and the GPU men checked every passenger for identification and destination. These courageous men and women doing their utmost to stay alive, achieved quite the contrary. We can only guess what happened to them when they were arrested; it was either death or the concentration camps. If they managed to escape the verdict of death in the “people’s” courts, receiving the questionable reprieve of hard labor, they never began their sentences. The combination of hunger, cold, and neglect took their lives on the way to the camps, at the railroad stations, or in the open box cars rolling north and east, in which they froze to death. The ones who escaped the roadblocks set up by the militia and GPU often became the victims of outlaws who terrorized the railroad lines and the open markets. The lucky ones who managed to return to their villages after these terrible experiences, and those who remained in the village, gradually lost their spirit and belief in salvation from their plight. Weakened by lack of food, freezing for lack of fuel, they simply had no more stamina left. The farmers sank deeper and deeper into resignation, apathy and despair. Some were convinced that starvation was a well-deserved punishment from God for believing in Communism and supporting the Communists during the Revolution. We heard that a few of those who came back had somehow managed to acquire food—mainly flour—but few of them were able to bring their treasures home. Those provisions, obtained under great hardships, had been confiscated by the state agents, or stolen by outlaws. All of these events convinced us that we had lost our battle for life. Our attempts to escape, or to secure food from other sources, were for the most part unsuccessful. We were imprisoned in our village, without food, and sentenced to die the slow, agonizing death of starvation.” [7]

How Bitter Harvest will depict the blacklist or other policies remains to be seen, but we do know that from the trailer that it will depict mass graves and depict prison executions, it also subtly infers that Yuri will be deported.

“We must Save ourselves or die.” - Ivan, Yuri’s Grandfather in Bitter Harvest.

There is one scene in the trailer in which Natalka tells her fellow villagers “we must continue the resistance” before the trailer jumps to a scene in which she is helping to set fire to a building. What you get here is an on screen echo of the way that women during the Holodomor actively participated in resisting Soviet Authorities.

One story in the Kyiv Oblast for example tells of a woman who burned down a state owned granary after party activists had threatened to take her belongings. For this, she received two years in prison (much like Natalka who in Bitter Harvest also ends up in prison presumably for her resistance activities).

Whilst a number of Ukrainian women were motivated into hiding food or disrupting Soviet authorities out of concern for their families or especially children, other incidents of resistance were arguably motivated by a sense of fatalism that death was simply inevitable.

On 1 March 1933, according to one Secret police report, a group of women in Khrystynivka attempted to stop a train after hearing rumors that it might contain some flour which they demanded be distributed amongst themselves. Fiercely desperate or desperately fierce depending on how you see it, the women were record shouting "they torture us with hunger, better to kill us all instantly – spray your gasses on us." The situation we are told was "forcibly resolved" (the women were most likely arrested) but as the document is broken the fates of these women is unknown [8].

Holodomor deniers have made much noise about Ukrainian resistance to Soviet rule which did extend to the burning of crops. The trailer depicts one Bolshevik telling Yuri and his fellow villagers that their land “now belongs to the state” which in Soviet ideological terms also meant that the state owned all the crops.

As we have already seen with Kosior’s remarks, he reported the widespread truism held by Ukrainians that the Soviet regime was indeed plundering Ukraine in favor of Moscow as a major motivation for anti-Soviet resistance. The propensity of Holodomor deniers to believe that the Ukrainian SSR was really indeed some workers paradise and to believe Soviet propaganda that the state was simply collecting all the grain so that it could *all* be redistributed back into the peasants in line with socialist thinking, yet there is nothing to support that.

The trailer seems to suggest that the resistance will lead to explosions and cavalry charges but one can suppose that it is to be expected that this is after all a popular production. Bitter Harvest began to be produced before the current war with Russia flared up, but the conflict has added to it being a timely and relevant production. It certainly looks lovingly made, and it looks like a film worth looking out for when it gets released in 2017.

Read also: History, Identity and Holodomor Denial: Russia’s continued assault on Ukraine

---

For added regional context. Here are two links to documents of the Holodomor in the Cherkasy Oblast.

http://www.archives.gov.ua/Sections/Famine/Publicat/Famine-Cherk-1932.php

http://www.archives.gov.ua/Sections/Famine/Publicat/Famine-Cherk-1933.php

[1] Cited here

[2] Гриневич Л. Голод 1928–1929 рр. у радянській Україні / Відп. ред. С. Кульчицький. НАН України. Інститут історії України. P305.

[3] Cited Here.

[4] The letter can be found in the “Архив Президента Российской Федерации” Fond 3, Record Series 61, File 794, p1-162.

[5] J. Bednarek et al., “Poland and Ukraine in the 1930’s – 1940’s, Unknown Documents from the Archives of the Secret Services. Holodomor The Great Famine in Ukraine. 1932–1933, No 27”, p111.

[6] Cited Here

[7] M Dolot, “Execution by Hunger: The Hidden Holocaust”, p175-6.

[8] J. Bednarek et al, “Op Cit”, No 104, p303.