For many observers in the West, Putin’s invasion of the Crimea came as a complete surprise. However, it fit into a longer pattern of Putin centralizing his political control within Russia itself beginning the day he took office. Dismantling Ukraine was the next logical step in his quest to reestablish Russia as a centralized superpower.

Putin’s assault on Russian federalism in the Middle Volga region was a precursor to his imperial actions in Ukraine. From the outset, Putin broke away from the legacy of Boris Yeltsin who, in his power struggle against Mikhail Gorbachev, embraced the principles of federalism for Russia, famously inviting the regions to “take as much sovereignty as you can swallow.” Federalism, by its definition, means that power is shared between center and periphery, which is indeed the only way that Russia can conform to the basic principle that every nation has a right to self-determination (this in not to validate the argument put forth by the “pro-federalists” in eastern Ukraine since every people has a right to self-determination in ONE territory, not twenty). Since the Russian Federation includes twenty one autonomous national republics, it is not possible for Russia to be a nation-state – Russia must either be a multi-national state or an empire. Without genuine autonomy in the ethnic regions, the “federation” in the name “the Russian Federation” rings hollow.

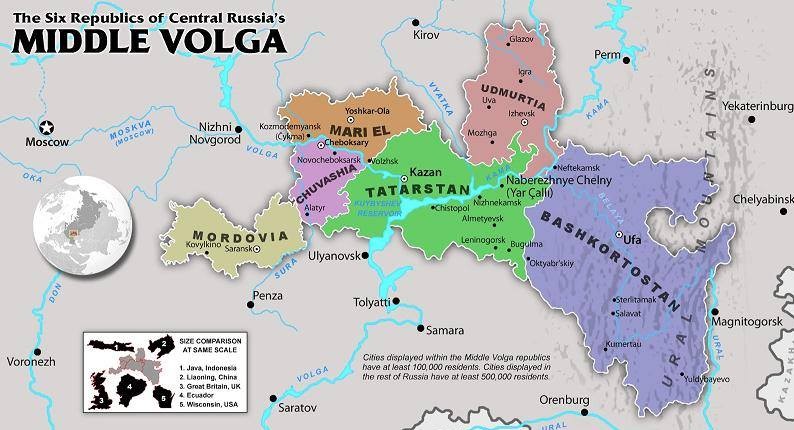

The Middle Volga region contains six autonomous ethnic republics: Mordovia, Chuvashia, Tatarstan, Mari El, Udmurtia and Bashkortostan. Tatarstan, under the leadership of Mintimir Shaimiev, was the one republic in Russia that had the strongest chance of achieving meaningful state sovereignty. As the heirs to three great civilizations (Volga Bulgaria, the Golden Horde and the Kazan Khanate), the Volga Tatars, numbering over five million in Russia, are Russia’s second largest nationality, second only to Russians. Ivan the Terrible’s conquest of the Kazan Khanate in 1552 represented the first time that Moscow incorporated a predominately non-Slavic state and thus became an empire.

In asserting state sovereignty, President Shaimiev was not seeking separatist goals, but understood that his efforts were contributing to making Russia into a genuine federation, something that makes Russia a stronger and more prosperous country. Tatarstan’s 1990 declaration of sovereignty was not proclaimed in the name of the ethnic Tatar people, but on behalf of the civically-defined Tatarstani people. Shaimiev sought to raise Tatarstan’s status both domestically and internationally, which included both substantive and symbolic efforts. Symbolic efforts included creating a new Tatar national flag, renaming the republic with a more Islamic name, Tatarstan (it was previously the Tatar ASSR), and reclaiming Kazan as a Tatar urban space. The Kazan Kremlin was developed as a cultural center of Kazan. The Museum of National Culture, as the centerpiece, displays a 200 foot statue called “Khurriyat,” meaning “freedom,” which replaced a statue of Lenin and symbolizes the rebirth of the Tatar people. In 1998, the Kazan Kremlin achieved recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

While symbolic efforts are important, Shaimiev recognized that, in order to earn legitimacy and support, it is important to actually improve the lives of citizens. Tatarstan managed to reject Yelstin’s disastrous “shock therapy” economic plan and maintain control of its oil revenues. With these revenues, Tatarstan demolished the unsightly Soviet bloc apartment buildings in Kazan and built modern apartments in their place. For this, Moscow presented Tatarstan with a “Creator of the Year” award. In these ways, Shaimiyev delivered on his goal to improve the peoples’ lives. Tatarstan achieved a minimum wage twice the Russian average and an unemployment level half that of Russia. In the mid-1990s, the famous financier George Soros called Tatarstan “the only region in Russia worthy of investment.”

One might imagine that the ethnically Russian population of Tatarstan would find these developments troubling, but, with the improvement in their quality of life, they have had nothing to complain about. As Shaimiev openly stated, “People live better here in Tatarstan, and this is mainly a result of Tatarstan’s sovereignty.”

Putin’s assault on Russian federalism began with the resurrection of the Stalinist legacy of the concept of “enemy nations.” His rhetoric surrounding the Second Chechen War made it clear that this was not a war against certain separatist elements, but an entire nation was being held as collectively guilty and was being collectively punished. On the pretext that if the Chechens were not stopped, a “brushfire of independence” would sweep up the Volga, Putin began a legal assault against federalism. This began with his 2000 “Federal Package” which created a new layer of federal bureaucracy by dividing Russia into seven “federal districts.” His main purpose was to intimidate local elites and to “harmonize” republican constitutions with the federal center.

The second phase of Putin’s attack on republican sovereignty began after the 2004 terrorist attacks in the North Ossetian town of Beslan. Putin’s rhetoric was now that the terrorists sought nothing less than the “disintegration of the country, the breakup of the state and the collapse of Russia.” Not for the first time in history, a terrorist attack was used as an excuse to rein in political freedoms. Putin’s “September Theses” ended regional elections by popular vote, instead having regional governors and presidents nominated by Putin and elected by regional parliaments (in effect, more of a “confirmation” than an election). This in particular brought strong criticism from both inside and outside of Russia, due to the fact that it violates the constitutional voting rights of Russian citizens. It also raised fears that it would provoke even more resentment and separatism from the ethic regions. In other words, it was a cure more harmful than the disease.

Putin’s post-Beslan reforms seemed to be the last nail in the coffin of Russian ethno-federalism, but Tatarstan, under Shaimiev’s leadership, was not about to roll over and surrender its sovereign rights. Above all, Tatarstan objected to the provision that its parliament would be disbanded if it failed two consecutive times to conform to Putin’s candidate. President Shaimiev, who was flexible in most matters, stood firm, stating that “Tatarstan will never agree to the dismissal of the State Council of Tatarstan – it is elected by and is the voice of the people.” This gave Putin little choice but to retreat from his hard line and concede that he had gone too far. At the State Council in Kaliningrad, Putin admitted that the de-regionalization policy was not workable and that he was transferring over 100 additional powers to the regions – all powers which do not infringe on Russia’s wholeness.

In 2005, during Kazan’s millennium celebrations, Shaimiev took the opportunity while sharing the stage with Putin to chastise him for his lack of trust in the regions, urging him to “trust them more” since they have “great potential to solve the many questions that can only be solved there”. As this quote shows, Shaimiev understood that the stakes in his power struggle with Putin to maintain Tatarstan’s sovereignty went far beyond the borders of Tatarstan itself. Shaimiev was championing a future for Russia as a decentralized, pluralistic state - in other words, genuine federalism.

Under Shaimiev, Tatarstan consistently made a point to voice a public independent opinion on Russia’s foreign policy. During the Yugoslav Wars, for example, while Moscow took the side of their Serbian “brothers,” Tatarstan publicly sympathized with the Muslim Bosnians. During the Chechen Wars, Tatarstan protested and urged Tatarstani citizens to avoid the military draft. If Tatarstan still possessed state sovereignty today, its government surely would have protested Russia’s illegal annexation of the Crimea, the homeland of the Crimean Tatars. In 2010, however, Moscow got the upper hand and replaced President Shamiev with Rustam Minnikhanov, a rank-and-file appointed official who could be easily replaced at any given moment. Such suppression of independent opinions has been one of the most consistent hallmarks of the Putin era.

Overall, the Putin era has been extremely destructive to the indigenous peoples of the Middle Volga region. For example, between the 2002 and 2010 Russian census, the total Mari population dropped from 604,298 to 542,000. The president of the Mari El republic since 2001 has been Leonid Markelov, a politician from Moscow who began his political career in Zhirinovsky’s extreme right Liberal Democratic Party. The LDP’s agenda included the abolition of ethnic republics, which should give some indication of Markelov’s sympathy for the indigenous Mari movement. The most alarming assimilation has been among Mordvins whose population dropped by almost 100,000 (from 843,350 to 744,237) between the two censuses.

It has been debated whether this assimilation has been voluntary or forced. The truth is somewhere between the two – what Rein Taagepera has called "induced" assimilation. For a small people in a globalized age, sovereignty over their own political affairs is their only hope of not losing their language and culture. Such a genuine separation of power is the very essence of the principle of federalism, a system of government that does not weaken a state, but, on the contrary, makes it more efficient, stable, prosperous and therefore stronger. Unfortunately, the world has turned a blind eye to these internal acts of imperialism, buying into a myth that Russia is a nation-state and these matters are Russia’s “sovereign affairs.”

However, the basis of international law is that a state’s sovereignty is not absolute. This is why the world has a moral responsibility to stand up for the norms established under international law that Russia has agreed to uphold, including UN standards, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), in addition to Council of Europe standards, such as the European Convention of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR), ratified by Russia in 1998. Furthermore, these rights are enumerated in the constitution of the Russian Federation which protects the right of all citizens to participate in cultural life (article 44).

Consolidating his power with Russia by illegally crushing the last vestiges of federalism within Russia was a necessary precondition for Putin to focus his ambitions on the “near abroad.” While Putin projects an image of monolithic unity to the world, the mere existence of the non-Russian Volga peoples contradicts these pretensions. The Volga region is one of the most richly diverse regions in Russia, and its existence not on Russia’s periphery, but in the very heartland of European Russia is perhaps the most powerful symbol of the reality that Russia is a diverse, pluralistic state. If the peoples of the Volga region continue to assimilate at the alarming rate we are seeing today, this fact will cease to be relevant and the world will suffer the consequences.