The word “reform” is being used in public discourse in Ukraine more frequently than ever before. The 2014 Euromaidan revolution was the second attempt by Ukrainians (after the Orange Revolution of 2004) to break with the corrupt and ineffective post-Soviet state. But this time Ukrainians aspired to “change the system, rather than the names”, as one Euromaidan motto put it.

![President Poroshenko stands on the backdrop of his electoral slogan, Zhyty po-novomu [Living the new way]](http://euromaidanpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/jyty.jpg)

The reform agenda is rhetorically omnipresent in Ukraine’s politics as well as in Ukraine-related discourse in the West. But much less attention has been paid to how ordinary Ukrainians understand reforms and to which reforms they see as priorities.

Reform agenda-setters: government, civil society, and the West

In an ideal world, citizens form policy agendas and elected officials implement policies to further these agendas. In practice, the political and economic elites that control the media are often able to impose their agenda on the public. In Ukraine, for example, a third of the population say they want to nationalise oligarchs’ property.

However, media channels – in most cases owned by the very same oligarchs – avoid the topic.

In Ukraine, three main groups currently form the reform agenda from above: the government, civil society, and the West. None of them necessarily have the same priorities as Ukrainian society as a whole.

The first group consists of the reformers in government, especially the young activists and business executives who entered politics after the Euromaidan. One such “professional reformer” is the deputy head of the Presidential Administration, Dmytro Shymkiv, who used to be the CEO of Microsoft in Ukraine. Since July 2014, he has chaired the Executive Committee of the National Council of Reforms.[1] Shymkiv authored the “Strategy of Reforms – 2020”, which lists more than 60 reforms and ten priorities. These priorities are governmental renewal, anti-corruption reform, judicial reform, decentralisation, deregulation and the development of entrepreneurship, reform of law enforcement, reform of the national security and defence system, healthcare reform and tax reform, an energy independence programme, and the promotion of Ukraine in the world.[2]

Shymkiv made bold promises in the “Strategy of Reforms –2020”: Ukraine’s GDP per capita would increase from $8,508 to $16,000 by 2020; the country would become one of the top 20 countries in the world in which to do business; foreign direct investment would increase to $ 40 billion; the average life expectancy would increase by three years; and military expenditure would grow from 1 percent to 5 percent of GDP. [3]

Shymkiv’s plans were similar to another 50 -page document titled “Coalition for Reforms”, signed by the new coalition in November 2014 – but, by then, defence sector reform had become the top priority.[4]

Poroshenko set a new trend of hiring foreigners to reform Ukraine; many were granted Ukrainian citizenship just a few hours before their appointment. US citizen Natalie Jaresko is minister of finance, Lithuanian investment banker Aivaras Abromavicius is minister of economy, and a Georgian, Alexander Kvitashvili, is minister of health. More recent arrivals include the former deputy interior minister of Georgia, Eka Zguladze, who took over the same post in Ukraine, the Estonian Jaanika Marilo, an adviser to Abromavicius, and Gia Getsadze, a lawyer from former Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili’s team, who is deputy minister of justice.

After the Yanukovych era, foreigners have a certain prestige.

Zguladze is expected to deliver a similarly effective police reform to the one she undertook in Georgia. Others are powerful agenda-setters, such as Saakashvili himself, the late Georgian economist Kakha Bendukidze, and the Polish economist Leszek Balcerowicz, all of whom act or have acted in advisory or symbolic capacities.

However, it remains to be seen how successful the foreigners will be in implementing reforms and maintaining their long-term symbolic authority. They face real challenges, including a lack of knowledge of the workings of Ukraine’s Byzantine bureaucracy and the absence of any independent political force behind them.

The next group of reformers is commonly described as “civil society”. This includes professionalised civil society, such as NGO activists and experts, who help draft reform legislation, push for its adoption, and monitor its implementation. Organisations of this kind include the Anticorruption Action Center, Transparency International, and others. The media also forms part of this group, as do active citizens who monitor the progress of reform.

Most civil society groups are sectoral; they lobby for and track the reforms most relevant to their particular professional environment. NGOs focused on fighting corruption helped to draft the anti-corruption package, while the SME community, one of the most active groups in Ukraine, concentrates on tax reform and deregulation.

One lobby group, the Reanimation Package of Reforms (RPR), looks at the broader picture. This body was launched soon after the revolution specifically to catalyse the reform process. It brought together a large network of experts, activists, journalists, lawyers, entrepreneurs, and other professionals, who set up different working groups to come up with blueprints for specific reform bills. On paper at least, the RPR and the government reform agendas are fairly similar.

A more diffuse but still vocal group includes online media, citizen journalists, and influential bloggers and opinion shapers who act as reform “watchdogs”. They tend to be more critical of the political class and of old ways of running the government, including corrupt practices and the lack of transparency in decision-making. Journalists have also campaigned for a public television service.

Because they are not part of the government or do not feel close to it (unlike some of the NGOs), such groups are freer in their criticism of the government and the way it leads reforms. For example, the new ministry of information was seen by some as a valid attempt to start working on Ukraine’s positive image at home and abroad at a time of war, but journalists condemned the idea as being both slightly Orwellian and an uncomfortable echo of Russian propaganda. They also pointed out that the new minister of information was a family friend of the president.

The third group of reform setters consists of various foreign donors, such as the International Monetary Fund, the US Agency for International Development, the World Bank, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The priorities of international donors and partners differ widely depending on their mandate and mission, which raises a real and worrying prospect of possible overlap and duplication of work, as well as of pulling the Ukrainian government and its scarce resources in different directions. Unsurprisingly, most foreign donors focus on cutting corruption and bloated state structures, along with energy sector reform. The IMF has repeatedly insisted on spending cuts and tax rises, and on unpopular increases in retail gas and heating tariffs, by 56 percent and 40 percent in 2014 and 20–40 percent in 2015–17.

Like domestic civil society, the West is very critical of the slow pace of Ukraine’s reforms and doubtful as to whether there is enough political will among Ukrainian elites to really change the country rather than just pass rafts of new laws. But the different groups – government, civil society, and Western donors – are most effective when they collaborate. For example, the bill to set up the National Anti-Corruption Bureau that came into effect in January 2015 was prepared by a group that included NGO professionals and experts, MPs and officials from the Ministry of Justice, and Western consultants.

However, it is clear that different agents, who have different agendas and answer to different constituencies, are not completely on the same page as regards every aspect of the reforms in Ukraine. The government tends to describe the IMF’s most unpopular measures as external pressures and does not “own” them in programmatic documents or official statements. Civil society also largely avoids lobbying for unpopular measures. Rightly or wrongly, society is clearly unhappy with the pace of reforms and the lack of positive results from the Euromaidan revolution to date.

The population’s reform agenda

Sociological data confirms that the elite and the public do not share the same reform agenda. The economic crisis and the ongoing war in the Donbas are the two most powerful factors influencing public opinion, but polls show that Ukrainians are more worried about their own economic and physical survival than about reforming their country.

Asked what they thought were the most urgent problems for Ukraine to solve, 79 percent of respondents said ending the war in the Donbas was most important.[5] Meanwhile, 48 percent said raising salaries and pensions was essential, 43 percent prioritised kickstarting economic growth, and 38 percent thought fighting corruption was urgent.[6]

Another poll at the end of 2014 showed that ordinary citizens perceive reforms primarily as a way of both bringing governmental officials to justice and of improving their own economic situation[7].

The question “What are the reforms for you?” had 30 options from which to choose. The most popular choices were: scrapping MPs’ immunity (58 percent), raising salaries and pensions (51 percent), and scrapping immunity for judges (48.3 percent) and for the president (34.4 percent).

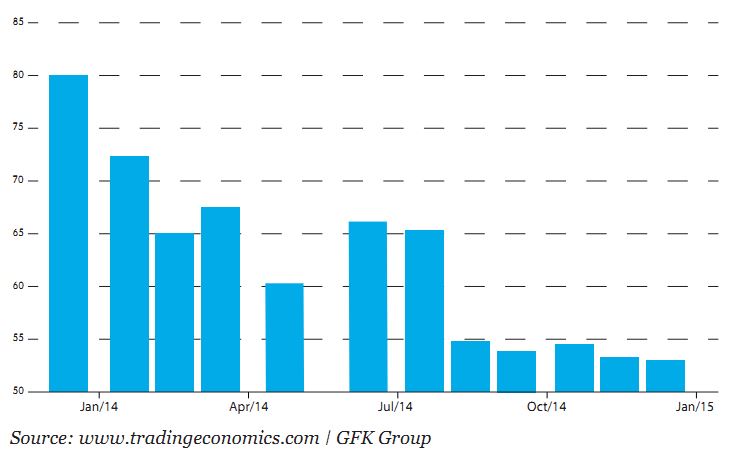

The standard of living of ordinary Ukrainians has plummeted dramatically since the Euromaidan. Ukraine’s economy is in its second year of recession, as the war ravages industry and investment. The decline in real GDP in the third quarter of 2014 was 5.1 percent, after drops of 4.6 percent and 1.1 percent in the first and second quarters. The depreciation of the exchange rate of the hryvnia to the dollar between January and October 2014 was 58.9 percent. The consumer confidence indicator has deteriorated dramatically, from 80.3 points in January 2014 to a low of 52.6 points a year later (see figure 1).[8]

Figure 1: Ukrainian consumer confidence

Ukrainians feel unsure about their future, especially since their government as well as Western observers have openly speculated about the possibility of default. Ukrainians also feel vulnerable, both because their own government could not protect Crimea and cannot resolve the Donbas conflict, and because foreign allies have shown that they are unwilling to engage militarily even after Russia invaded Ukraine.

At the same time, Ukrainians feel strongly that their officials should be punished for decades of mismanagement and corruption: 58 percent prioritised scrapping the immunity of MPs and 34 percent would decrease the salaries of state officials, including ministers and MPs, to the national average – even though many anti-corruption experts would argue for doing the opposite.

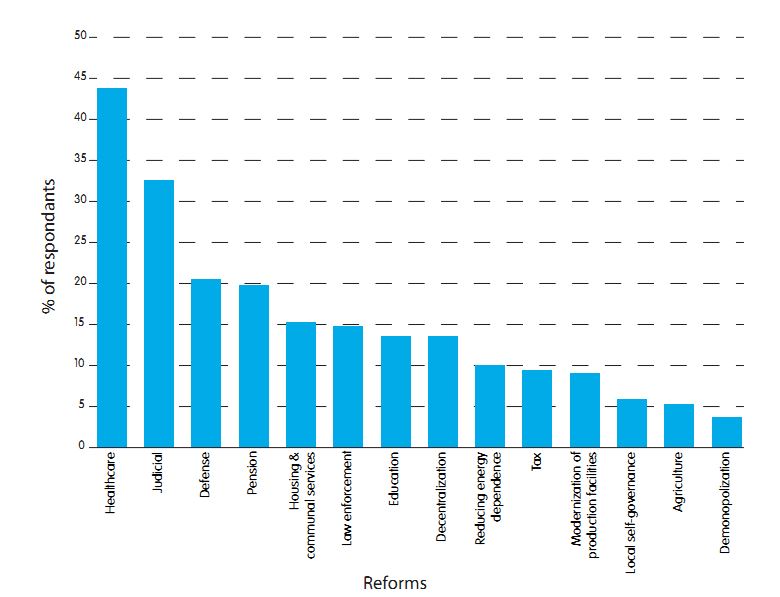

In terms of sectoral reform, Ukrainians’ top priority was healthcare reform, followed by judicial and defence reforms (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Which reform do you see as a priority?

This is hardly surprising, given the deterioration of Ukraine’s healthcare system since Soviet times as well as the fact that Ukraine has one of the lowest life expectancies in Europe. But while judicial and defence reforms are high on the agendas of both the government and civil society, healthcare reform receives much less attention.

The poll also demonstrated that some reforms favoured by international actors, such as deregulation, are much lower down the public agenda. They remain the brainchild of a professionalised ruling elite and of foreign advisers who understand the link between deregulation and boosting the economy. For Saakashvili, recently appointed by Poroshenko as the Head of Advisory International Council of Reforms, deregulation is the most important reform of all[9]. But only 0.9 percent of the public see deregulation of the permit system as a priority.

Between war and reform

The October 2014 parliamentary elections were supposed to dispel early frustrations with the lack of reform. The vote produced a pro- reform majority and removed most of the reactionary forces from parliament.

But the new parliament has been slow to foster change. Some doubt that the current political elite will ever summon enough political will to enact meaningful change. Both the president and the prime minister have said that it is difficult to instate reform while Ukraine is at war. “After spending most of the day looking at military maps and studying the situation on the frontline, it’s not easy to switch straight away to addressing the subject of promoting peace”, Poroshenko complained at the end of January[10].

Civil society argues that the war should not serve as an excuse for everything, although while the war continues they temper their criticism. They also understand that there is an external enemy that could exploit any new unrest to create a hypothetical “Maidan 3”. The war has also refocused civil society’s attention from pushing for reforms in government to volunteering in the Donbas war.

Not only did the war make citizens pay less attention to reforms, it also thwarted some of the reform processes. The lustration reform that started after the revolution as a result of bottom-up pressure aimed to clean the state apparatus of corrupt officials from the Yanukovych era and collaborators with the KGB. But the war has short-circuited the process. The anti -oligarch movement was also stopped as the oligarchs came to be seen as allies of the state in the war with Russia.

However, Ukrainians understand that even if it is harder to reform during the war, structural reform remains a precondition for Ukraine’s ability to defend itself militarily and thus to survive. Ukraine’s military campaign has been constantly weakened by government inefficiency and corruption. The army leadership has not been lustrated and has not adopted modern methods of military command, creating considerable mistrust between NGOs supporting the army and its commanders.

Conclusion

Ukrainians do want reforms, but they feel disoriented and endangered. It is hard to ask society to take the lead in reforms when the majority are either struggling to survive the economic crisis or worried about their personal security.

The overall pace of reform is glacial, but there are several effective teams and individuals inside and outside the government striving to transform the country. The West should rely on these individual reformers and provide finance only in sectors that have concrete reform programmes, like that of the traffic police launched by Eka Zguladze.

Ironically, Ukraine is still a long way from creating the kind of democratic model that the Kremlin clearly fears. But if the Russian regime manages to crush Ukraine’s ongoing democratic experiment and redraw the borders of Europe, the future of the whole of Europe will be insecure.

Other articles from this series:

Serhiy Leshchenko: Sunset and/or sunrise of the Ukrainian oligarchs after the Euromaidan revolution?

Volodymyr Yermolenko: Russia, zoopolitics, and information bombs

Anton Shekhovtsov: Spectre of Ukrainian "fascism": Information wars, political manipulation and reality

Olena Tregub: Do Ukrainians want reform?

[hr]1 The National Reform Council (NRC) was established by presidential decree in August 2014 to consolidate and coordinate the country’s reform efforts, plus a Reform Executive Council and Project Management Office (PMO) in support.

2 “Dmytro Shymkiv: ‘Strategy of Reforms – 2020’ is the achievement of European living standards”, the Official Website of the President of Ukraine, 29 September 2014, available at http://www. president.gov.ua/en/news/31305.html (hereafter, “Dmytro Shymkiv: ‘Strategy of Reforms –2020’”).

3 “Dmytro Shymkiv: ‘Strategy of Reforms – 2020’”.

4 “Koalitsiiuna Ugoda”, Samopomich, November 2014, available at http://samopomich.ua/wp- content/uploads/2014/11/Koaliciyna_uhoda_parafovana_20.11.pdf.

5 “Gromads’ka Dumka: pidsumki 2014 roku”, the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation, December 2014, available at www.dif.org.ua/ua/polls/2014_polls/jjorjojkpkhpkp.htm.

6 Other responses were: 30 percent – curbing inflation, 27 percent – reducing unemployment, 26 percent – medical and pension reform, 24 percent – energy security, and 22 percent – purging state institutions of corrupt officials.

7 Poll by the KIIS, 4–19 December 2014, published by Zerkalo Nedeli, available at http:// opros2014.zn.ua/reforms.

8 “Ukraine Consumer Confidence”, Trading Economics, 2015, available at www.tradingeconomics. com/ukraine/consumer-confidence.

9 “Hromadske International. The Sunday Show – ‘Putin is a Little Bit Weird’, Says Fmr Georgia President Saakashvili”, Hromadske.tv, 15 February 2015, available at www.youtube.com/ watch?v=TM7Zo_Qotik.

10 “War takes precedence over reforms in Ukraine”, DW, 4 February 2015, available at www.dw.de/ war-takes-precedence-over-reforms-in-ukraine/a-18234907.