The number of people in Crimea identifying as ethnic Ukrainians has fallen by 232,000 between the 2001 census conducted by the Ukrainian government and the 2014 census conducted by the Russian occupation authorities, a decline that has reduced the percentage of ethnic Ukrainians on the peninsula from 24.0 to 15.1 percent.

That contributed both to a decline in the total population of Crimea from 2.4 million to 2.285 million over the same period and to an increase in the ethnic Russian share of the population from 60.4 to 65.3 percent as well, according to data presented by Andrey Illarionov.

In order to understand that these are not natural shifts but the result of what Illarionov calls “the catastrophic factor

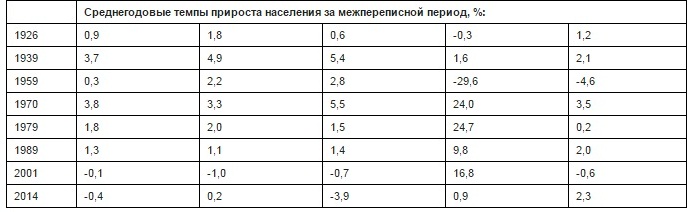

” of the Russian Anschluss, he presents data on the total numerical and annual percentage changes of these two ethnic groups for the preceding (1989-2001) inter-censal period and those of the most recent one (2001-2014).

In the earlier period, the number of ethnic Russians declined from 1.64 to 1.45 million with annual percentage declines of 1.0 percent while the number of ethnic Ukrainians fell from 626,000 to 457,000 with annual percentage declines of 0.7 percent. But in the latter one, Russians increased by 0.2 percent while Ukrainians fell by even more, 3.9 percent a year.

In the course of the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, “the ethnic composition of the population of Crimea was subjected to significant changes, the Russian analyst continues, the most important of which during that period was “the demographic catastrophe which affected the Crimean Tatars.”

According to Illarionov, “one can with a high degree of certainty assert that the qualitative changes in the ethnic composition of the population of Crimea took place in the course of the seven or eight months preceded the last census,” that is, “between February 27 and October 14, 2014.”

“In this case,” Illarionov says, “the sharp decline in the number of Ukrainians in Crimea was called forth evidently both by the mass departure of Ukrainians from Crimea and the conscious change by some of them of their official ethnic self-identification.”

And to appreciate just how large those two factors are, he suggests, one could compare the number of ethnic Ukrainians in fact with the number of ethnic Ukrainians who would have been in Crimea at the end of 2014 if the same rates of change from the previous inter-censal period had continued.

If that had been the case, there would have been 524,000 ethnic Ukrainians in Crimea, not the 180,000 fewer that the Russian census takers recorded in October 2014. That difference, he concludes, is a useful and appalling measure of “the cost of the Putin adventure for the Ukrainians of Crimea.”