“The mental gap between Ukraine and Russia is growing, and the trajectories of the two country are ever more strongly diverging,” according to Maksim Artemyev in an assessment of new Ukrainian laws opening Soviet-era secret police archives, de-Sovietizing the country’s toponymy, and revising key judgments about the past.

In a comment on RBC.ru, Artemyev says that “public access to the archives of the special services is an important decision intended to ensure the past will not be repeated. Now Ukraine wants to go along this path,” but “in Russia in contrast, hopes for such a decision were forgotten and buried long ago.”

Yesterday, the Verkhovna Rada passed on first reading a law intended to simplify the access of citizens to the archives of Soviet force structures, including the KGB. Such public access is “an important decision,” one that Ukraine joins the countries of Eastern Europe in making but on that in Russia hopes for something similar were “long ago forgotten and buried.”

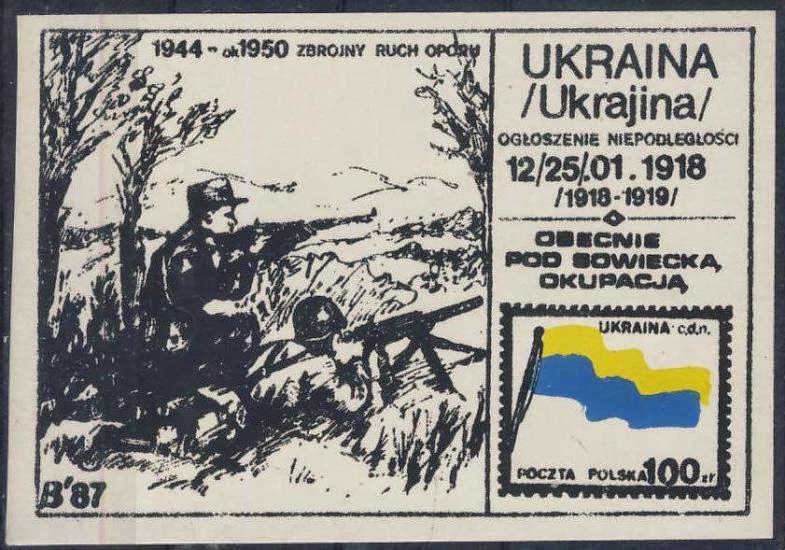

That step, along with others that redefine the 1939-1945 conflict in Europe as World War II rather than “the Great Fatherland War,” celebrate the end of the war in Europe on May 8 rather than May 9, end the condemnation of the anti-Moscow resistance, and call for the elimination of all Soviet place names move Ukraine ever further from “a common past” with Russia.

At the end of the 1980s and in the early 1990s, many Russian liberals hoped for something similar with regard to the archives and place names, but “there was not a broad social demand for this” and the powers that be soon were able to block access to the archives and limit name changes.

As a result, Russia but not now Ukraine “decided to turn away from its own history or more precisely did not want to say farewell to its accustomed picture.” As a result, Artemyev says, “Russia in many respects remains a Soviet state with a corresponding ideology and system of values.”

Also yesterday, he continues, the Ukrainian parliament adopted several other “important pieces of legislation,” including one law that bans the use of symbols from the communist and national socialist past, the taking down of monuments to all communist leaders, and the elimination of all place names linked to the Soviet and communist leadership.

Implementing all these pieces of legislation is not going to be easy. “Taking down monuments [to Lenin] is one thing; renaming thousands of streets, squares and allies” is another. It will be expensive and for some longtime residents inconvenient, and there will be resistance as well as questions about what names should be employed instead.

But in all these cases, whatever the problems there may be, Ukraine has shown that it plans to follow the European path rather the Russian one, the historian says. “In Russia, in 1990-1992, there were attempts to change place names. But like with many other reforms, the move stopped not having gone even half way.”

Leningrad was renamed St. Petersburg, and Sverdlovsk was renamed Yekaterinburg, but the oblasts around them remained what they were: Leningrad and Sverdlovsk. And while some streets in some cities have been renamed, most Russians continue to “live on Lenin Prospects, and the centers of their cities are decorated with statues of Lenin.”

The continuing presence of Lenin’s mausoleum on Red Square, Artemyev says, is “one of the most visible testimonials of the piddling nature of real changes after 1991.” Putin today is so popular that “if he decided to carry out the mummy and close that institution, no mass protests would take place.”

And the fact that he has not done so and that his regime continues “to support the relics of Sovietism,” the Russian historian says, “likely shows that “they are important and dear to [the leadership] in and of themselves and not because [any move against them] would generate social tensions.”