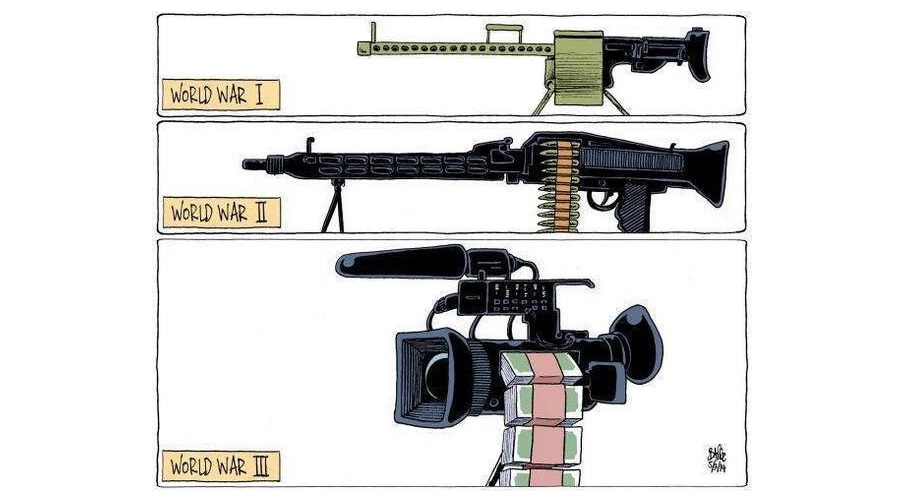

Moscow now views the Internet as its primary propaganda channel in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania because that medium reaches the young whereas Russian-language television to the extent that it has an impact at all affects primarily those of pension age, according to Jacek Jan Komar.

On the one hand, this shift reflects the fact that nearly a generation after the end of the Soviet power in the Baltic countries, those who rely on Russian language television are passing from the scene, while young people who prefer the Internet to television are becoming an ever larger part of the population in all three.

And on the other, it highlights the fact that Moscow has adopted a long-term strategy for increasing its influence in the Baltic countries rather than seeking any quick propaganda victories, a decision some may see as a victory for the Baltic governments but that others will recognize as a more serious long-term threat.

In an interview with Belarus’ Charter 97 portal, Komar says that some Lithuanians are celebrating a Russian decision to stop broadcasting a Russian-language news program as “a sign of Lithuania’s victory in the Kremlin’s undeclared information war against the Baltic countries.” But that is a mistake.

In an interview with Belarus’ Charter 97 portal, Komar says that some Lithuanians are celebrating a Russian decision to stop broadcasting a Russian-language news program as “a sign of Lithuania’s victory in the Kremlin’s undeclared information war against the Baltic countries.” But that is a mistake.

“In fact,” he says, “the popularity of this program is already long in the past; its main audience consisted of people of pension or immediately pre-pension age.” The costs of producing such a program were high, and the returns to Moscow quite low given that few younger people ever watched it.

After Moscow invaded Ukraine

, it stepped up its propaganda efforts against the Baltic countries, and the Baltic governments responded in a variety of ways – from creating a Russian-language television program in Estonia to banning Russian television channels in Lithuania. But in an important respect, they missed the point of what Moscow is trying to do.

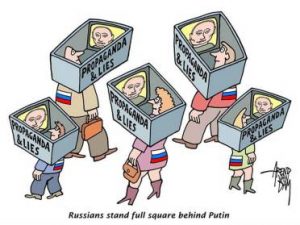

By taking such steps, the Baltic governments provided Moscow with the opportunity to claim, albeit without foundation, that the three were violating freedom of speech. That is very much part of the Russian information war against the Baltic states because Moscow in the very first instance wants to present the three to the West as unreliable countries.

“The Kremlin is trying not necessarily to show that the neighboring countries are taking a Russophobic position but rather that they have still not matured to democracy, human rights and freedom of speech. Appealing to the West, Moscow is not shy of accusing the Baltic countries of totalitarianism,” Komar says.

But even more, he suggests, the Baltic focus on television has caused some in those countries to ignore the dramatic increase in Moscow-sponsored activity on the Internet, activity that is far cheaper for the Russians to engage in and far more likely not only to reach the young but to spill over into the local language segments of the net and thus have a greater influence.