Vladimir Putin’s childish and thoughtless actions recall the last years of Imperial Russia with the worsening situation at home opening the way to a new 1905 revolution and the worsening situation abroad opening the way to a new 1914, according to former MGIMO professor Andrey Zubov.

In an interview on Ukrainian channel Espresso TV yesterday, Zubov argues that Putin by his failure to exercise a minimum of good sense has driven Russia to the edge of a situation like that which produced the failed revolution of 1905 and which led to the disastrous beginning of World War I.

“The present situation recalls 1914” because like his tsarist predecessor, Putin is acting on the basis of revenge rather than geopolitical calculation, an approach that opens the way to uncontrolled escalation. “Revenge is not a spiritual or Christian or even a political thing.” It is the response of a child to the experience of adversity, the foreign policy specialist says.

At the same time, Zubov continues, the situation recalls 1905, with living standards falling after a long rise and with “whole groups of the working population in the first instance the long-haul truckers” and the St. Petersburg dockworkers beginning to protest in ways that the Kremlin does not seem to have any answer for except repression.

And just as at the end of Romanov times, these two trends are feeding off each other and making each other worse, with the regime trying to engage in “a good little war” to win back popular support and the population increasingly impoverished and angry because of the regime’s failure to get a victory.

The current escalation of the conflict with Türkiye is “very bad for the ruling group in Moscow,” the former MGIMO professor says. Russia has no allies and is now “isolated from the entire world.” If things proceed as they are now going, there will be a war of some kind “and even a small war is a catastrophe for Russia.”

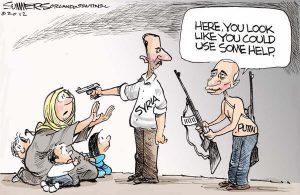

“Putin is trying to support Assad in order to retain influence in the Middle East, but Assad is a political corpse. In Syria, he has no future; in principle, he does not have a future anywhere. Therefore, this is an absolute political mistake,” and it is leading Russia into “a dead end” from which it will be increasingly difficult to escape.

It is far from clear what Putin’s calculations are. “Even in Ukraine, the prospects of his policy looked more realistic than in Syria. In Ukraine, it was possible to hope for a revolutionizing of the south and east,” although that didn’t happen, “but in Syria there are not even any such chances.”

It is far from clear what Putin’s calculations are. “Even in Ukraine, the prospects of his policy looked more realistic than in Syria. In Ukraine, it was possible to hope for a revolutionizing of the south and east,” although that didn’t happen, “but in Syria there are not even any such chances.”

“The Sunni majority, to which the Kurds also belong, fiercely hates the Assad regime, and anyone who supports Assad will be their enemy, including Putin.” Whether the Kremlin leader understands that or not is far from clear, and the kind of language he and his supporters are using suggest that he is acting from emotion rather than calculation.

“This is not geopolitical behavior; this is irrational and comparable with the actions of the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries when leaders did not reflect about the real consequences of their psycho-emotional processes,” Zubov says. But even most of them acted with more careful calculation than has Putin.

Stalin and Hitler may have acted out of anger, but they always combined it with “an almost mathematical accounting” of forces. Today, “there is none of that.” Instead, Russia like some other post-Soviet states is being run by “a dilettante” who is acting out of motives like personal revenge rather than geopolitical calculation.

According to Zubov, “anyone from the street could do what Putin is doing. Power, especially the absolute power which Putin has, turns the head of he who has it, and as the old saying puts it, corrupts absolutely.” But Putin could still get out of this situation if he would stop and reflect, Zubov suggests.

Indeed, Syria and ISIS could give him a chance. The entire world is now focusing on Islamist terrorism and “Putin really should become a member of this coalition,” something he could do by giving up his lone ranger approach. If he were to do so, he could use his gains to “resolve the Ukrainian problem at the same time.”

“Unfortunately,” Zubov continues, “the Kremlin has turned out to be incapable of this.” Instead, it relies on “two types of arms – boldness and lies, and with their help and with the help of real weapons, it is trying to resolve all world problems. But this is a dead end. Even the Ribbentrops and the Molotovs were more skilled diplomats.”

Putin’s foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, whom Zubov has known since their time as students, “has completely lost his capacity to act as a good diplomat.” Instead, he and Vitaly Churkin [the Russian representative] at the UN are forced to lies. “A diplomat never lies!” Zubov says. He may not tell all the truth, he may hide things, “but to lie when everyone knows you are lying is not diplomacy.”

Lavrov should have resigned when the issue of the annexation of Crimea was being discussed because he certainly would have recognized that “this is not in the interests of Russia.” But he didn’t, and so he has been forced to continue to lie, the former MGIMO professor continues.

Even Soviet foreign minister Andrey Gromyko “did not permit himself to act” as Lavrov now is. Yes, he was “’Mr. No,’ … but he was a tough negotiator, not a banal liar.” Unfortunately, Russian diplomacy now is “a lie.” And what may be even worse, the propensity to lie has now spread to the Russian military.

Russian commanders are now saying things that everyone knows are not true. Zubov recalls that his father, a Soviet admiral, “always said that if a military man lies, he isn’t a military man and should have his shoulder boards ripped off. The honor of the uniform requires him to speak the truth or be silent, but not to lie.”

That Russian generals lie shows that “they already are not generals.”