The emerging nation-states of the 18th and 19th centuries were based on existing national identities. In contrast, Ukraine had obtained her statehood (Ukr.: derzhavnist’) before her national identity was firmly grounded. The newly independent Ukrainian state which emerged in 1991 was based on a, in some parts of the country, weak national consciousness. The periods of Ukrainian national sovereignty in the modern era serving as historical references for a sense of national identity were short-lived:

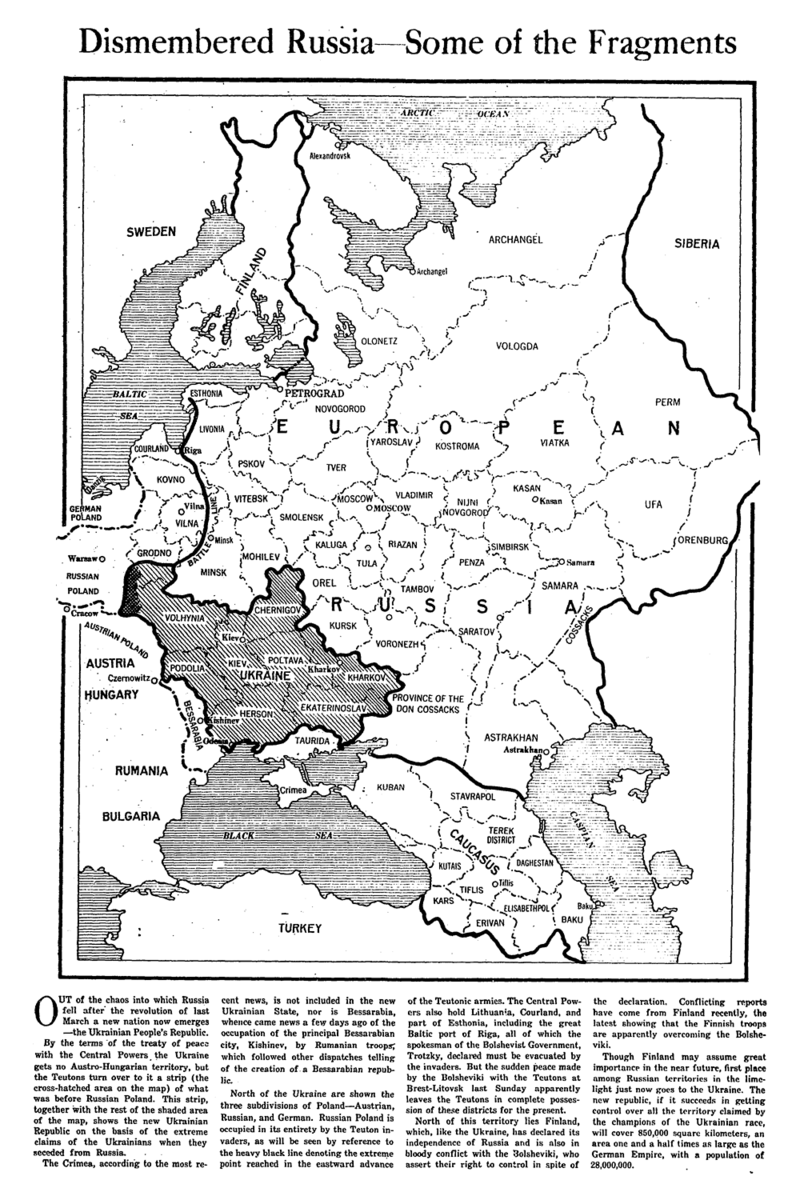

the Ukrainian People’s Republic (Ukr.: Ukrains’ka Narodna Respublika), founded in 20 November 1917, and its Declaration of Independence in Kyiv, 22 January, 1918, and

the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic (Ukr.: Zakhidno-Ukrains’ka Narodna Respublika),[1] and its Declaration of Independence in Lviv, 1 November, 1918).

Both ‘People’s Republics’ united on January 22, 1919.

From the mid-1980s, Mikhail Gorbachev’s glasnost and perestroika reforms allowed for the development of a Ukrainian independence movement. On September 8-10, 1989, the founding meeting of the People’s Movement of Ukraine for Reconstruction (Ukr.: Narodnyy Rukh Ukrainy za perebudovu), took place in Kyiv. Rukh (literally ‘the movement’) was to be the driving force for the referendum on Ukrainian independence held on December 1, 1991.

Ukraine’s recently won independence under threat

The independence which Ukraine obtained as a ‘gift’ through the dissolution of the Soviet Union[2] in 1991 resulted in a latent national identity crisis. This crisis reached an acute stage when President Yanukovych provoked a fundamental endangerment of the country by his abrupt change of course in the outward orientation of Ukraine. As a consequence of his unexpected refusal to sign the Association Agreement with the European Union as planned at the Eastern Partnership Summit on November 28-29, 2013, in the Lithuanian capital Vilnius, Ukraine was threatened by alienation from Europe and integration into the Eurasian project of Russia’s President Putin. Ukraine’s independence would have been de facto reversed. Yanukovych’s regime would have further adapted itself to the autocratic systems of the Eurasian political space, as embodied by Putin in Russia, Lukashenka in Belarus and Nazarbayev in Kazakhstan.

Until the very end, the outcome of the Maidan uprising was uncertain. It was only Yanukovych’s escape on the evening of February 21, 2014, that brought victory for the Maidan protesters over his auto- and kleptocratic regime. The fact that the victory of Maidan has not brought stability to Ukraine is primarily due to the “hybrid war” of infiltration, secession and attrition which Putin subsequently unleashed on Crimea, and in the Donbas. Following the flight of his unofficial ‘viceroy’ Yanukovych, Russia’s President Putin feared losing Ukraine irretrievably to the West. By officially annexing the Crimean peninsula and covertly intervening in the Donbas region through delivery weapons, intelligence, supplies, first irregular and later regular troops etc., Putin has, however, succeeded in creating the very reality which he sought to prevent.

As a result, the Ukrainian population’s orientation towards Europe became in 2014 stronger than ever before.[3] Ukraine has emerged from a prolonged national identity crisis with a strengthened consciousness of national identity. The integrative potential of the Maidan movement and the catalytic effect of Russia’s aggression have combined to produce nothing less than a rebirth of the Ukrainian nation. Both the Maidan movement and Russia’s war in Ukraine have become new Ukrainian national founding myths increasingly overshadowing earlier historical reference points from the pre-Soviet, Soviet and early post-Soviet periods. However, an acute economic crisis – and possible impending default – as well as the desperate asymmetrical war which the country is fighting with Russia, are now driving Ukraine into an existential crisis. Ukraine is not only fighting for its territorial integrity - the country is fighting for its survival as a sovereign state. The recent consolidation of national identity will prove to be a necessary precondition if Ukraine is to overcome this crisis.Ukraine is not only fighting for its territorial integrity - the country is fighting for its survival as a sovereign state

[hr][1] This proto-state was formed in the Eastern part of formerly Austrian-Hungarian crown land Galicia (Ukr.: Halychyna).

[2] In their historical meeting on December 8, 1991, in the state residence “Viskuli” at the Belarusian national park Belovezhskaia pushcha, the three presidents Boris Yeltsin (Russian Federation), Leonid Kravchuk (Ukraine) und Stanislav Shushkevich (Belarus) sealed the dissolution of the Soviet Union and decided, to replace it with the Commonwealth of Independent States / CIS (Russ.: Sodruzhestvo Nezavisimykh Gosudarstv / SNG). The agreement became known as Belovezha Accords (Russ.: Belovezhskie soglasheniia).

[3] Even Ukraine’s accession to NATO, which in past opinion surveys was rejected by the majority of the Ukrainian population, may now find a positive response in a referendum to be possibly held, in the future.

The “hybrid war” Russia is waging against Ukraine and her aggressive propaganda against this country are direct consequences of the victory of the Maidan movement in Kyiv. By reversing the course of Ukraine’s geopolitical orientation, President Yanukovych had effectively put himself and his country in Moscow’s hands. In some sense, the Ukrainian President had demoted himself to the rank of a provincial Russian governor. Yet, as a result of Yanukovych’s flight, Ukraine eventually slipped from the Russian President’s hands. With it went Putin’s dream of a new empire. Without Ukraine, Putin’s geopolitical ambition of creating a Eurasian Union capable of providing a counterweight to the European Union cannot be fulfilled.

For most Ukrainians, the idea of war with Russia was unimaginable until 2014. In the eyes of many Ukrainians, Russia maintained its status as cultural lodestar even after Ukraine became independent. Now Russia has become an enemy nation. On March 1, 2014, the Federation Council of the Russian Federation authorized President Putin to deploy Russian troops in Ukraine – according to the amended Article 10 of the Federal Law on Defence of 1996 (Zakon “Ob oborone”).[4] This decision came as a shock to many Ukrainians: “The Russian part of me died…” – MacFarquhar quotes, in The New York Times, young economist Aleksey Ryabchyn who has become a member of the parliamentary bloc of Yulia Tymoshenko’s Batkivshchyna (Fatherland) party.[5]

Russia’s undeclared war has forced Ukrainians to take up arms and defend their country’s independence militarily – something which had not been necessary during the relatively peaceful transition in 1990-1991. Russia’s military aggression reinforces Ukraine’s nation-building process. It strengthens the formation of a national Ukrainian identity – and also makes the process irreversible. Russia’s President Putin has thus become the midwife of the Ukrainian nation. Writes Andrew Wilson of University College London:

“Now Putin appears to be making a new Ukrainian nation before our eyes.”[6]

As a Ukrainian scholar put it,

“Mr. Putin has fulfilled the dream of Ukrainian nationalists” by forging a strong sense of Ukrainian national identity, infused with a heavy dose of anti-Russian sentiment.[7]

In an interview for the Russian state-controlled television channel NTV on October 19, 2014, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said: “We must not lose Ukraine [...]. For us Ukraine is a brother nation (Russ.: bratskii narod, brotherly people) sharing historical, cultural and philosophical roots with us, not to mention language and literature.”[8] However, these ties were cut by President Putin’s fratricidal war. Members of the same family, friends on either side of the border, do not speak to each other anymore. If they do, they generally end up arguing and hurling abuse. It looks increasingly like both nations may be enemies for generations to come.

One state – two Ukraines: “Post-Soviet schizophrenia”?[9]

Ukraine is perceived by many in the international community as a divided country. However, the perception of ‘one State, two countries’ does not imply that Ukraine can be divided along a clear geographical demarcation line, as the renowned Ukrainian author Mykola Riabchuk remarked.[10] The Dnieper River (Ukr.: Dnipro, Russ.: Dnepr’), that runs through the middle of the country and its capital Kyiv, serves more to unite than to divide Right Bank Ukraine (Pravoberezhna Ukraina, West) from Left Bank Ukraine (Livoberezhna Ukraina, East). Rather than serving as a dividing line, the Dnieper constitutes a symbolic backbone of Ukraine.

The divisions underpinning the ‘two Ukraines’ thesis are often said to be most evident in the two opposing ‘poles’ of the Ukrainian geopolitical spectrum - the cities of Lviv in the west (Eastern Galicia), and Donetsk (Donets Basin) in the east. These two cities are outwardly so disparate that they could conceivably belong to two entirely different civilizations.[11] The architecture of Lviv is Central European whereas Donetsk represents the typical proletarian style found in dozens of indistinguishable Soviet industrial towns.

Local attitudes vary as much as the architecture. These differences can also be found in the satellite towns and rural communities located in the hinterland of these two regional capitals. The population of West Ukraine is broadly ‘bourgeois’, with a strong sense of patriotism and European identity. The population in East Ukraine, particularly in the Donbas region, is more ‘proletarian’ in character, and tends to be ideologically oriented towards Russia – or rather, towards the extinct Soviet Union.

In between these two extremes, with their ambiguous boundaries and borders lies the vast expanses of Central Ukraine (Ukr.: Tsentral’na Ukraina) with the capital city Kyiv. The Ukrainian capital is representative of the country as a whole, thanks to the influx of people from every region – especially after Ukrainian independence in 1991. These ‘two Ukraines’ have always been evident in Kyiv. After 300 years of Russification and 70 years of Sovietization, they have penetrated each other and begun to merge together.

The vast landmass between Lviv and Donetsk is heterogeneous, with each region boasting its own combination of attitudes towards the issues of Ukrainian, Russian, European and Soviet identity. In Central Ukraine, these divisions often result in individual ambivalence. According to Riabchuk, this is the result not only of ‘regional, cultural and linguistic differences,’ but also of the ‘atomizing effects of Soviet totalitarianism upon Ukrainian society.’[12]

Until the events which began with the Maidan protests, the great majority of Ukrainians were internally divided. Once could say that they have – or rather, had until recently – in the words of Goethe’s Faust: ‘two souls in one breast.’ Many Ukrainian citizens had, to one degree or another, an indeterminate, ambiguous or fluctuating sense of national identity. The result was not ethnic anger, but rather national apathy. Ukrainians were said to constitute a ‘disinterested, indecisive, amorphous mass.’[13] Their confused sense of national identity made individual Ukrainians easy prey for propaganda and manipulation.

Bilingualism in Ukraine

The broad outlines of Ukraine’s electoral divisions were particularly consequential in the election of “pro-Russian” candidate Leonid Kuchma to President in July 1994. He and his designated successor Viktor Yanukovych, in the presidential elections of 2004 and 2010, specifically wooed Russian-speaking voters by denouncing Western Ukrainians – in line with Soviet tradition – as ‘nationalists’. In the days of the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic, ‘Ukrainian nationalists’ were presented as enemies not only of the Soviet system and Communist Party, but also of the “socialist” Ukrainian people. The charge of ‘bourgeois nationalist’ carried a sentence of 5 to 10 years imprisonment. By first instrumentalizing the ‘language question,” President Kuchma promoted the disunity of the country through his pro-presidential and paradoxically titled party “For a United Ukraine” (‘Za Yedynu Ukrainu’).[14] Yanukoych’s Party of Regions fuelled existing regional resentment in the east and south of Ukraine even against Central Ukraine and Kyiv in particular.

As a result of the 2010 national elections, Viktor Yanukovych, a native of the Donets Basin (Donbas),[15] assumed power as President, bringing with him the Russophile and semi-criminal elite of the Donbas to Kyiv. During the four years of his rule, however, President Yanukovych did not fulfill the election pledge which he and his party made in every election campaign – namely to grant the Russian language the status of second official state language in Ukraine, but only pushed through a law that allows granting Russian the status of a second administrative language in certain regions of Ukraine.[16] Following the annexation of Crimea, Russian President Putin whipped up latent separatist tendencies in parts of the population of the Donbas region in order to provoke a war of secession.

The bilingualism of Ukraine results from three centuries of Russian language dominance in large parts of present-day Ukraine. Following the 17th century Treaty of Pereiaslav, Left Bank Ukraine largely belonged to the Russian Empire. Since the divisions of Poland in the 18th century, a large part of Right Bank Ukraine also fell under Russian imperial rule. In present-day Ukraine, it is not only the Russian language which requires protection – the Ukrainian language is arguably even more in need of safeguarding. If its status as sole state language had not been anchored in the constitution of the new post-Soviet state, the Ukrainian language would have experienced a fate similar to that of the Belarusian language: it would have disappeared from public life.

Also on Euromaidan Press: Switch to Ukrainian for protection against Russian occupation, Ukrainians urge compatriots

After gaining independence from the collapsing Soviet Union, the ‘language question’ became important to all of the Newly Independent States (NISs). The former Soviet republics opted to make the titular language (i.e. the tongue of the dominant nationality of the republic) the official state language. In its language law of October 1989, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (Ukr.: Ukrains’ka Radians’ka Sotsialistychna Respublika; Russ.: Ukrainskaia Sovetskaia Sotsialisticheskaia Respublika) made the Ukrainian language the sole state language (Ukr.: derzhavna mova) of independent Ukraine. The Supreme Soviet of the (then still existing) Soviet Union reacted to this challenge in April 1990 by declaring the Russian language de jure the official language of the entire Soviet Union (i.e. including the Ukrainian Republic) – which it had been de facto all along.

Even if Ukraine succeeds in overcoming the political identity crisis, the country’s cultural identity transformation will continue. Many educated Ukrainians regard the classical Russian literature a core element of their own cultural universe. They find themselves currently caught in an internal conflict. Neil MacFarquhar draws a pertinent literary parallel.[17] Mikhail Bulgakov, a Ukrainian novelist of worldwide acclaim, who wrote in Russian, is lauded in his native city Kyiv. However, Bulgakov himself despised the Ukrainian language and belittled the idea of an independent Ukraine. A recent Russian film based on one of Bulgakov’s greatest works, The White Guard, depicts the aversion of the urban, Russian-speaking Kyiv elite following the capture of the city by rural, Ukrainian-speaking armies after the Russian Revolution of 1917. The Ukrainian State Film Agency banned the film, arguing that it constitutes not a work of art, but (anti-Ukrainian) propaganda. Ludmila Gubiauri, director of the Bulgakov Museum in Kyiv, dodged the question of Bulgakov’s national sympathies. For her, Bulgakov is simply ‘a great citizen of Kyiv’.[18]

For most Ukrainians, independence came ‘almost overnight’. Up until 2014, Ukrainians have not had to choose between their Ukrainian or Russian identities. Today, they are increasingly finding that they must choose, according to sociologist Irina Bekeshkina, director of the Democratic Initiatives Foundation: ‘Ukrainian people are now deciding who they are as people’.[19] Paradoxically, Putin has managed to destroy the part of the complex Ukrainian identity which he sought to defend: many Ukrainians’ inner attachment to Russian culture expressed in Ukrainian bilingualism in everyday life.Ukrainian people are now deciding who they are as people

[hr][4] On December 2009, the Federation Council empowered the President of the Russian Federation „to take decisions on the operational deployment of the Russian Federation Armed Forces beyond the territorial boundaries of the Russian Federation […] in order to fulfill the following tasks: […] 3) to protect Russian Federation citizens beyond the territorial boundaries of the Russian Federation from armed attack… (Russ.: sootechestvenniki za rubezhom, compatriots, fellow countrymen, fellow Russians).” The authorization of the deployment of Russian troops in Ukraine was repealed in order to uphold the official position of the Russian government, that Russia is not a party to the Ukraine conflict. See: European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission): Opinion on the Federal Law on the Amendments to the Federal Law on Defence of the Russian Federation, adopted by the Venice Commission at its 85th Plenary Session (Venice, 17-18 December 2010). German sympathisers with Russian pretensions (Putin-Versteher) compare the deployment of Russian troops in Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova, with “out-of-area” operations of NATO.

[5] Neil MacFarquhar, “Conflict Uncovers a Ukrainian Identity Crisis over Deep Russian Roots,” The New York Times, 18 October 2014 <http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/19/world/europe/conflict-uncovers-a-ukrainian-identity-crisis-over-deep-russian-roots-.html?_r=0>.

[6] Andrew Wilson, “Five things the West can learn from the Ukraine Crisis,” Quartz, 8 October 2014 <http://qz.com/277502/five-things-the-west-can-learn-from-the-ukraine-crisis/>. See also: Andrew Wilson, Ukraine Crisis: What It Means for the West. New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 2014.

[7] As quoted by Steven Pifer [US Ambassador to Ukraine in 1998-2000], Trip Report: Mid-September Impressions from Kyiv. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2014

<http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/up-front/posts/2014/09/15-trip-report-impression-kyiv-pifer>.

[8] “Lavrov: dlia Rossii Ukraina – ėto bratskii narod…,” TASS, 19 October 2014 <http://itar-tass.com/politika/1517687>.

[9] „The two Ukraines“ (Ukr.: dvi Ukrainy; Russ.: dve Ukrainy), a term coined by Mykola Riabchuk already in 1992: Mykola Riabchuk, “Two Ukraines?” East European Reporter, vol. 5, no. 4 (1992). “Post-Soviet schizophrenia” was the headline of an article in The Economist, 4 February 1995, p. 27.

[10] Mykola Riabchuk, “Ukraine: One State, Two Countries?” Kyiv Post, 12 December 2014.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] In his electoral campaign in 1994 then presidential candidate Kuchma warned, that the Russian speaking part of Ukraine would be forcefully ukrainianized, should Western Ukrainians come to power.

[15] His birthpace is Yenakieve (Russ.: Enakievo) in the Donetsk Oblast.

[16] The new language law passed on July 3, 2012, initiated by Yanukovych’s Party of Regions allowed the recognition of Russian and minority tongues (Russian cannot be considered a “minority language”) as official regional languages, that is to say, allowed their use for official purposes in respective regions.

[17] MacFarquhar, “Conflict Uncovers a Ukrainian Identity Crisis over Deep Russian Roots.”

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

The Maidan movement began spontaneously on November 21, 2013, and was soon being branded as ‘Euromaidan’ due to the pro-EU integration dynamic of the initial protests. Kyiv’s academic youth led the early protests against President Yanukovych’s reversal of the country’s European integration course. They also protested against the prospect of Ukraine’s integration into President Putin’s rival Eurasian project.

In the course of the following weeks, what had begun as a pro-European movement (slogan: ‘Ukraine is Europe!’ - Ukr.: ‘Ukraina – tse Yevropa!’) gradually morphed into a much broader popular uprising against the kleptocratic regime of President Yanukovych and against the ‘occupation’ of the whole country by the Donetsk elite. It was also an uprising against the political ‘Eurasianization’ of Ukraine, following the model of the Russian Federation and the former Soviet republics of Central Asia. As the protests grew, the number of European Union flags on display decreased, while the number of blue-and-yellow national flags of Ukraine increased.[20] More and more frequently the ‘People of Maidan’ (Ukr.: narod Maidanu) chanted the slogan: ‘Glory to Ukraine!’ (Ukr.: ‘Slava Ukraini!’). Again and again, the Ukrainian national anthem was intoned on Maidan. It became fashionable to wear Ukraine’s traditional embroidered shirts (Ukr.: vyshyvanka, Pl. vyshyvanky) and to speak Ukrainian in public. The Maidan movement nationalized itself and consolidated the hitherto insecure identity of many Ukrainians.

On January 19, 2014, after weeks of peaceful protests, sections of demonstrators turned to violent confrontation with the riot police forces guarding the government district in downtown Kyiv. Members of the nationalist Right Sektor group would later boast of initiating the clashes.[21] This outbreak of violence came in response to the adoption of draconian anti-protest legislation on 16 January, 2014, by the parliamentary majority of the ruling Party of Regions and the Communist faction. These ‘emergency laws’, were soon dubbed the ‘dictatorship laws’ (Ukr.: Zakony o dyktature) by the opposition. They were signed into law by President Yanukovych the following day. Attempts by riot police to enforce the new legislation and forcibly clear the tent city on Maidan met with resistance from volunteer units of the Madains ‘Self-Defence’ (Ukr.: Samooborona Maidanu). These self-styled ‘Defenders of Maidan’ (Ukr.: oborontsi Maidanu) were divided into ‘Hundreds’ (Ukr.: sotnya, Pl. sotni; their leaders being named ‘sotnyky’) in reference to traditional Cossack cavalry formations.

Without this violent confrontation, the Maidan movement may not have achieved its victory. If the Maidan movement had failed, Russia would probably not have annexed Crimea and would not have ignited war in the Donbas. While, in Mahatma Gandhi terms,[22] a ‘victory attained by violence’ is an ambivalent one, President Yanukovych would, following the alternative scenario, in all probability have led Ukraine into Putin’s Eurasian Union[23] of post-Soviet dictatorships, and thereby de facto subjected his country again to Moscow’s rule – a gloomy prospect for Ukraine’s youth.

The victory of the Maidan movement led to ‘revolutionary-parliamentary’ regime change in Kyiv. Arguably, the revolutionary violence was, given the circumstances, justified – as was the Storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, in Paris. President Yanukovych’s regime was criminal. He himself and his clan (‘The Family’) enriched themselves to an unprecedented degree at the expense of the Ukrainian State, effectively robbing the Ukrainian people. The idea of waiting to vote him out of office in the regular presidential elections scheduled for 2015 was hopeless: Yanukovych had already consolidated most state prerogatives and enormous resources in his hands. Using “political technology,” he may have secured a second term for himself.

In the immediate aftermath of the Maidan massacre of 20 February, and with the aim of avoiding further bloodshed, the foreign ministers of Germany, France and Poland, Franz-Walter Steinmeier, Laurent Fabius and Radoslaw Sikorski, negotiated an agreement between President Yanukovych and the leaders of the three parliamentary opposition factions: Arseniy Yatsenyuk (Fatherland Party, Ukr.: Bat’kivshchyna), Vitalii Klitschko (UDAR Party) and Oleh Tyahnybok (Freedom Party, Ukr.: Svoboda). Russia’s Human Rights Commissioner, Vladimir Lukin, participated in the negotiations, but refused to co-sign the agreement.

This agreement was a waste of paper from the outset, because the leaders of the parliamentary opposition had no control over the revolutionary processes at play within the Maidan movement. The Maidan movement rightly rejected this agreement, because it stipulated “early” presidential elections in December 2014 – only two months before the regular election date (January / February 2015). Yanukovych would have ensured his ‘victory’ in these elections by employing all of the administrative, financial and judicial means at his disposal – and he would have taken revenge afterwards.

The revolutionary Maidan movement was democratically legitimized through subsequent Ukrainian elections – if any subsequent correction were needed. The presidential elections in May 2014 were won by the ‘Maidan Candidate’ Petro Poroshenko, with an unprecedented first round landslide majority of 55%. In the parliamentary elections in October 2014, pro-Ukrainian and patriotic parties gained an almost two-thirds-majority.

As a result of the annexation of Crimea and military intervention in the Donbas, Russian President Putin effectively excluded almost 4 million traditionally pro-Russian voters from taking part in these 2014 Ukrainian national elections. These pro-Russian constituencies had previously served as the bedrock of electoral support for Viktor Yanukovych’s Party of Regions. Altogether 27 electoral districts, 12 on the Crimean peninsula (1,8 million elegible voters), 9 out of 21 in the Oblast Donetsk, 6 out of 11 in the Oblast Luhans’k (1,9 million voters in both Oblasts) did not take part in the elections. In this sense, the ‘temporary loss’ of Crimea and one-third of the Donbas has actually made Ukraine more ‘Ukrainian’. Today the country is more patriotic and more pro-European than ever before.

From ‘Anti-Maidan’ to war of secession in the Donbas

The ‘People of Maidan’ (Ukr.: narod Maidanu) did not represent the entire population of Ukraine. Large sections of the population in eastern and southern Ukraine did not share in the national sentiment which was awakened by the Maidan movement. President Yanukovych’s Party of Regions rallied these forces in defense of their leader (slogan: ‘Yanukovych is our President!’, Ukr.: ‘Yanukovych – nash president!’). In the major cities of east and south Ukraine, a so-called Anti-Maidan movements soon emerged. Paid „anti-demonstrators“ were, for instance, taken by bus and rail from Eastern and Southern cities to Kyiv. In a park next to the building of the Verkhovna Rada (Parliament) a stage was set up for them, where the Party of Regions temporarily staged an “Anti-Maidan”.

These activists initially imitated the tactics of the Kyiv Maidan movement. However, wooden bats were soon replaced by firearms looted from the arsenals of the local (often openly sympathizing) security services. After the annexation of Crimea by Russia, some separatist-minded Russian speakers thought the time had come to attempt to seize the Donbas by force of arms. The secession movement of ‘New Russia’ (Russ.; Novorossiia)[24] was supposed to encompass the whole of South East Ukraine (Russ.: Yugo-Vostok).

Read also: Meet the people behind Novorossiya’s grassroots defeat

The existence of resentment towards Kyiv among many ethnic Russians and Russian-speaking ethnic Ukrainians in eastern and southern Ukraine should not be taken to imply that a majority of this discontented segment of society wished to join Russia, or follow the example of the Anschluss of Crimea. According to polls taken before the war, only one-third of Donbas residents held genuinely separatist sentiments. This explains why Putin’s secessionist Novorossiia project struggled in the wake of the awakening of Ukrainian national sentiment among the majority of the people living in the territory earmarked to become “New Russia.” With the exception of the Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts, the other six eastern and southern oblasts of Ukraine which had been identified by Moscow as part of Novorossiia did not rally to join Putin’s separatist adventure. Even in the Donbas itself, the separatists have initially managed to exert military control over merely one-third of the macro-region. This modest success has only proved possible because losses of combatants and weapons are offset by continuous replenishment from Russia. The Russian President miscalculated over the Ukrainian reaction to his military intervention: ‘New Russia’ did not fall into his lap as Crimea had done. Putin did not foresee that by supporting separatism in Ukraine, he would arouse militant Ukrainian patriotism.

[hr][20] There was a simultaneous increase of the (historical) red and black flags of the Ukrainan Insurgent Army / Ukrayins’ka Povstans’ka Armiya / UPA, 1943 -1956), the military arm of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (Ukr.: Orhanizatsiya Ukrayins’kykh Natsionalistiv / OUN), adopted by the “Right Sector”.

[21] “Right Sektor” (Ukr.: Pravyy Sektor) originated as a merger of several ultra-nationalist organizations (UNA-UNSO, „Tryzub imeni Stepana Bandery“, „Patriot Ukrayiny“, „Karpats’ka Sich“, „Bilyy Molot“, Chornyy komitet, Komitet vyzvolennya politv’iazniv), which were politically insignificant until the Maidan events. November 15, 2013, is considered to be its founding date. On March 22, 2014, the “Right Sector” was officially registered as a political party by the Ministry of Justice.

[22] “Victory attained by violence is tantamount to a defeat for it is momentary." Mahatma Gandhi: Satyagraha Leaflet No. 13, 3 May 1919.

[23] The first stage, the “Customs Union” (Russ.: Tamozhennyi soyuz) was established on January 1, 2010. The intermediate stage, the „Eurasian Economic Union“ (Russ.: Evraziiskii ekonomicheskii soiuz) came into force on January 1, 2015.

[24] In addition to the two Oblasts of Donbas, Donetsk and Luhans’k, the Oblasts Kharkiv, Dnipropetrivs’k in the East, and Odesa and Mykolayiv in the South.

In research on nationalism, ‘nation’ is defined either in essentialistic (primordial) or in constructivistic (voluntaristic) terms.

The constructivist concept of nation in the meaning of Benedict Anderson’s ‘imagined community’[25] has largely established itself against essentialistic concepts (essence, language, territory etc.), which regard national identity as unchangeable. According to Ernest Gellner, ‘nations are the artifacts of men’s convictions.’[26]

In Germany, the primordial concept of nation prevailed in the past. ‘Nation’ was understood as an ethnic, historical and cultural ‘community of common destiny’ with unalterable characteristics. This essentialistic concept of nation is attributed to Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814).[27] The extent to which this primordial nationalism remains current in Germany is evident in the recent so-called PEGIDA movement and its offshoots. Most Ukrainian nationalist groups – notably the Svoboda (Freedom) Party and Praviy Sektor (Right Sector) – adhere to the primordial concept of nation.

In France, as long ago as 1882, Ernest Renan turned against essentialistic definitions in his famous speech at the Sorbonne about the concept of ‘nation’[28], and contrasted his concept of the ‘free will of citizens’ with the ‘German’ primordial concept: A community of citizens of differing ethnic backgrounds forms a ‘nation’ (a ‘nation of will’, a ‘nation by choice’, Germ.: Willensnation) based on the citizens’ shared memories of the past – and based on their desire to live together in the future (‘daily plebiscite’). A nation is the product of a historical process: the past, the present and the future are the key factors which constitute the principe spirituel of a nation.

In France, as long ago as 1882, Ernest Renan turned against essentialistic definitions in his famous speech at the Sorbonne about the concept of ‘nation’[28], and contrasted his concept of the ‘free will of citizens’ with the ‘German’ primordial concept: A community of citizens of differing ethnic backgrounds forms a ‘nation’ (a ‘nation of will’, a ‘nation by choice’, Germ.: Willensnation) based on the citizens’ shared memories of the past – and based on their desire to live together in the future (‘daily plebiscite’). A nation is the product of a historical process: the past, the present and the future are the key factors which constitute the principe spirituel of a nation.

Thus, according to Renan, national identity evolves from collective historical memory. A large part of the population in eastern Ukraine, however, does not share a common historical memory with the people of western Ukraine over the central event in recent world history: World War II. The other factor, the ‘daily agreement to live together in the future’, is exactly what the minority separatists in the Donbas do not want.

Nowadays, Renan’s concept of a ‘collective memory’ and Anderson’s concept of the ‘imagined community’ are considered to be the essential components for the understanding of the concept of national identity. According to the concept of Jan Assmann, who combines these two components, societies imagine self-images that form through generations as a cultural memory, and thus construct an identity..[29] As a common imagination consisting of shared memories, national identity is a cultural and not a political construction. And just like personal identity, national identity is constructed narratively.

Formerly characteristic features of national identities are no longer distinguishing criteria. National cultures are being homogenized through globalization. Today’s European nations differ in practical terms only in mentalities. Nevertheless – or perhaps for this very reason – the search for national identity is back in fashion. Today’s France, for example, questions its traditional assimilation policy in view of a ‘critical mass’ of immigrants from other cultural backgrounds. In 2009, the French Minister for Immigration and National Identity Eric Besson[30] initiated a campaign on the issue of ‘national identity’. All of France participated in a discussion around the question: “What does it mean to be French?” Henri Guaino, special advisor to President Sarkozy, explained to the German weekly newspaper Die Zeit: ‘If the sense of belonging to a nation were a matter of course nowadays, then there would be no need for a debate. But if one finds oneself in a situation of uncertainty about what the ‘nation’ is, in a crisis of identity, in a crisis of orientation, then identity becomes a subject of political debate.’[31] By asking questions regarding the very ‘essence’ of the nation, the government of France turned away from the hitherto valid French concept of nation, as formulated by Ernest Renan, and turned towards the essentialist (‘German’) concept.

Meanwhile, the German publicist Michael Böhm believes that national identity has vanished.[32] He argues that under the conditions of global migration and inter-cultural marriages, the essentially ‘pre-political’ and ‘pre-legal’ idea of the identity of a nation has completely lost its plausibility. In fact, however, the importance of national identity has not declined, either because of individualization, or because of globalization, or as a result of supra-national unification processes such as the European Union. Elections to the European Parliament demonstrate this fact, with Euro-skeptic and nationalist parties gaining an increasingly high share of votes. Economic and social problems have provoked the renaissance of primordial nationalism of a kind which had long been dismissed as outdated throughout Europe and also in Russia.

Primordial nationalism implies a comparison with other nations; it accentuates the characteristics of a nation in contrast to other nations. This does not per se mean disregard for others, but it does set one’s own nation apart from other nations. The anthropological concept of an ethnically homogeneous nation, a ‘people’ as a (biological) ‘descent community’, which almost inevitably leads to calls for ethnic cleansing, did not die out completely with the military defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945. It remains very much alive in ‘folkish’ (Germ.: völkisch) delusions and the desire to protect minorities of compatriots abroad (Germ.: Volksdeutsche; Russ.: sootechestvenniki) by force of arms from alleged discrimination by the titular nation.

The raging nationalism of a large majority of Russians – inflamed by Russian President Putin and fanned by the Russian media – proves the continuing susceptibility of nations to aggressive nationalism. The process of national self-assertion in Ukraine, which was initiated by the Maidan movement, now risks appearing anachronistic. However, the catch-up consolidation of a national – and European – identity at the present time makes sense because it distances Ukraine from its Soviet identity – and from Putin’s Russia.

Patriotism or ‘positive nationalism’?

For obvious reasons, the term ‘nationalism’ has negative connotations. In neutral terms, however, ‘nationalism’ is the political instrumentalization of national identity. Nationalism pursues political objectives which may very well be legitimate. For example, in the case of ‘nations without a state’, this can involve laying the foundations for a future state (for example, a Kurdish state), or the achievement of national independence, as in the case of Ukraine in the recent past.

The Czech Historian Miroslav Hroch states that in any population, national identity dominates all other collective identities. Hroch advises us not to label a positive national sense of belonging as ‘nationalism’.[33] ‘Patriotism’ is considered to be ‘positive nationalism’, a political virtue. The former German Federal President Johannes Rau explained the difference between patriotism and nationalism in a novel manner: ‘A patriot loves his fatherland. A nationalist despises the fatherlands of others.’ However, in political practice, the term ‘patriotism’ also lends itself to misuse, just like ‘nationalism’. In the past it has frequently proved to be a semantic labeling swindle.

One might also mention that modern national consciousness, as emerged from the French Revolution (1789-1799), was originally emancipatory – in the sense that it implied overcoming class boundaries. In the Wars of Liberation (1813-1815), Germans were gripped by an unprecedented patriotism, which expressed itself in the desire for a united nation state. Until the ‘March Revolution’ of 1848-49, the ‘yearning for national unity’ allied itself with the ‘fight for freedom’ and for democracy. During the ‘Second Empire’, after the ‘(Smaller) German’ unification (1871), this liberal, republican patriotism[34] changed into a presumptuous nationalism.[35] Around the end of the 19th century, the concept of ‘cultural nation’ (Germ.: Kulturnation, Friedrich Meinecke) became popular in Germany,[36] which defined ‘nation’ less in categories of (political and military) power, but rather through a common culture,[37] a term by means of which the national sentiment of the ‘delayed nation’ (Germany) could be conceptually grasped. It had a slightly conceited overtone.[38] During the so-called Third Reich, under the rule of Adolf Hitler, the imperial nationalism of the Second Empire degenerated completely into a totalitarian ideology[39] – into psychopathic racism.A patriot loves his fatherland. A nationalist despises the fatherlands of others

After the military defeat of National-Socialist Germany in 1945, ‘patriotism’ became a ‘non-word’ because of its previous belligerent misuse. A positive identification with the German nation became taboo. As a result of these attitudes, a considerable part of society in West Germany rejected German Reunification in 1990. The concept of ‘constitutional patriotism” (Germ.: Verfassungspatriotismus), unknown outside the Federal Republic of Germany, as propagated by Dolf Sternberger and Jürgen Habermas, is incongruous, since the constitutions of all modern democratic states resemble each other. Universal human rights and basic values, political institutions and processes are anchored in all of them. Differences relating to state structure – federalism or centralism – do not constitute an emotional basis for patriotism.

[hr][25] Anderson, Benedict Richard O’Gorman, Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. First published 1983; revised and extended edition London / New York (Verso, formerly New left Books) 1991. Under the influence of Eric Hobsbawm’s The Invention of Tradition Anderson adopted the constructivistic approach from sociology, according to which the perception of reality is the result of an intersubjective, societal construction process. According to the social anthropologist Ernest Gellner, nationalism is a sociological requirement of modern industrial society. See Ernest Gellner, Nations and Nationalism. Oxford 1983.

[26] „...nations are the artefacts of men’s convictions and loyalties and solidarities…”; quoted from Jiři Musil, “The Prague Roots of Ernest Gellner’s Thinking,” in: John A. Hall, Ian Charles Jarvie (ed.), The Social Philosophy of Ernest Gellner. Amsterdam (Editions Rodopi B.V.) 1996, p. 40.

[27] Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Reden an die deutsche Nation (Addresses to the German Nation). Berlin 1808.

[28] Ernest Renan, Qu’est-ce qu’une nation? Lecture at Sorbonne on March 11, 1882. Paris 1882.

[29] Jan Assmann, “Kollektives Gedächtnis und kulturelle Identität (Collective Memory and Cultural Identity),” in: Jan Assmann / Tonio Hölscher (eds): Kultur und Gedächtnis (Culture and Memory), Frankfurt a. M. 1988, pp. 9-19.

[30] Eric Besson, former socialist, at that time member of the ruling party UMP / Union pour un mouvement populaire.

[31] Gero von Randow, “Wie Nicolas Sarkozy mit einer Kampagne zur nationalen Identität das Land spaltet” (How Sarkozy’s campaign on national identity splits the country),” Die Zeit, No. 46 / November 2009.

[32] Michael Böhm, “Nationale Identität ist verflogen (National Identity has vanished),“ Deutschlandradio Kultur, Politisches Feuilleton, 05.10 2012; <http://www.deutschlandradiokultur.de/nationale-identitaet-ist-verflogen.1005.de.html?dram:article_id=223242>.

[33] Hroch, Miroslav, “Learning from Small Nations. Interview,” New Left Review 58, Juli-August 2009, pp. 49-50. See also: Hroch, Miroslav, Die Vorkämpfer der nationalen Bewegungen bei den kleinen Völkern Europas. Eine vergleichende Analyse zur gesellschaftlichen Schichtung der patriotischen Gruppen, Prag 1968. Revised version in English: Social preconditions of national revival in Europe. A comparative analysis of the social composition of patriotic groups among the smaller European nations, Cambridge 1985. See also: Miroslav Hroch, “Zwischen nationaler und europäischer Identität,” in: Pim den Boer, Heinz Duchhardt, Georg Kreis, Wolfgang Schmale (eds): Europäische Erinnerungsorte, Band 1, Mythen und Grundbegriffe des europäischen Selbstverständnisses, München (Oldenbourg) 2012, pp.75-89.

[34] It was after the victory over Napoleon was suppressed by Metternich’s Restauration (Vienna Congress 1814 / 1815).

[35] „The World shall be healed through the German (national) character.” Germ.: “Am deutschen Wesen soll die Welt genesen”.

[36] This can be contrasted with the French “state nation” (Germ.: Staatsnation), not to be confused with “nation state”.

[37] „Kultur“ is a term, which is not identical with “civilization,” Germ.: Zivilisation.

[38] “Land of poets and thinkers” (Germ.: „Volk der Dichter und Denker”).

[39] “You are nothing – your people is everything”.

In Russia the very existence of a Ukrainian nation is often questioned and even negated.[40] This is not only the case in Russia. In Germany, too, attempts to ‘understand’ Putin’s conduct are often justified by the assertion that Ukraine is an ‘artificial nation’. Former German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt stated in the German weekly newspaper Die Zeit that Ukraine is ‘not a nation’, indicating that it is still a controversial question among historians, ‘whether a Ukrainian nation exists at all’.[41] According to the thesis put forward by Jens Jessens, also printed by Die Zeit: ‘Kyiv and the East have always been Russian.’ [42] Such claims reveal insufficient knowledge of the topic commented.

The origins of the Ukrainian national movement lie in the 19th century, at the time of the ‘awakening of nations’ in other parts of Europe. In the early 19th century, Kharkiv University was an important center of the emerging Ukrainian national movement. The first volume of the monumental History of Ukraine-Rus, written in Ukrainian by Ukrainian historian Mykhailo Hrushevskyi, appeared in Kyiv in 1913. Hrushevskyi would later become the head of the Central Rada of the ‘Ukrainian People’s Republic’ (1917-1918). Hrushevskyi countered the official imperial narrative of the common history of all East Slavs with descriptions of the separate development of the ‘Russian People’ and the ‘Ukrainian People’.

For the intellectual representatives of the Ukrainian nation, the February Revolution[43] of 1917 opened up historic opportunities to realize the dream of independence. On March 17, 1917, after the abolition of Tsarist authority, a Central Council (Tsentral’na Rada) gathered in Kyiv[44] in order to form a provisional Ukrainian government. This body elected Hrushevskyi as Chairman (March 20). On June 28, 1917, all legislative and executive powers were passed over to a nine-member General Secretariat chaired by Volodymyr Vynnychenko. The Provisional Government in Petrograd recognized the General Secretariat in Kyiv as the supreme governing body of Ukraine, and vice versa.

On January 22, 1918, the Central Council proclaimed the independence (‘IV. Universal’) of the Ukrainian People’s Republic (Ukrains’ka Narodna Respublika / UNR),[45] which on February 9, 1918, concluded a separate peace[46] with the Central Powers (Mittelmächte) at Brest-Litovsk.[47] Berlin historian Jörg Baberowski’s statement that Kyiv and Kharkiv are ‘not sites of national self-assertion’ for the Ukrainian nation[48] ‘absolutely fails to comply with the current state of academic research’, concluded Anna Veronika Wendland of the Herder Institute in Marburg (Germany).[49]

In Germany, questions over the existence of a Ukrainian nation go hand in hand with an ‘unreflecting acceptance of Russian, Soviet and post-Soviet concepts of identity.’ Franziska Davies (University of Munich) too opposes the ‘imperial rhetoric’ of Putin’s apologists in Germany. Even if a nation is a social construct – the idea of a nation alone generates a historical effect and thus becomes reality. It is not helpful, Davies argues, to disqualify nation-constructs as ‘artificial’ entities.[50]

In her open letter, Wendland accuses Baberowski of claiming that the character of the Ukrainian nation is a (social) construct, that this nation is an ‘invention of the West,’ and that it therefore does not exist. For these reasons, the state into which this nation organized itself since 1991 could justifiably be dismantled piece by piece and incorporated into the territory of the ‘likewise constructed Russian imperial nation’.[51] Backed by her personal research experience in Ukraine, Wendland also criticizes Baberowski’s misjudgment of the personal attitudes of Russian-speaking Ukrainians towards the Ukrainian state. ‘A new historical phenomenon’ can presently be observed in Ukraine which is occurring in real time. This is ‘the genesis of a political, multilingual Ukrainian nation’, a process occurring ‘under external pressure’. In the current ‘revolutionary discussion’, which is conducted at least fifty percent in Russian, ‘it is not the concept of a nation in the 19th century sense that plays a role’ (as Baberowski argues), but rather ‘the expression of the will of a new generation of Ukrainians – Ukrainian- as well as Russian-speaking – and the will to create a pluralistic and democratic society’. It is ‘wonderful that in Ukraine right now a political nation is arising.’[52]It is not the concept of a nation in the 19th century sense that plays a role, but the expression of the will of a new generation of Ukrainians to create a pluralistic and democratic society

Nations ‘need enemies’ in order to become ‘what nationalists have invented’. Ukraine is being presented as a ‘nation of victims, suppressed for centuries’, according to Baberowski. ‘Historians refute myths. They are the worst enemies of nationalists.’[53] After this statement, the renowned narrator of Stalin’s Rule of Violence[54] raises a rhetorical question before answering it implicitly in the affirmative: ‘Was the post-Stalinist Soviet Union really a ‘prison of nations’? Was it not a successful model of management of inter-ethnic conflicts?’[55] As the independence movements within the Soviet Union republics at the end of the 1980s (Baltic states, South Caucasus, Ukraine) and in some of the ‘autonomous republics’ of the Russian Federation (North Caucasus) prove, the post-Stalinist Soviet Union was indeed a ‘prison of nations’.

Ukraine is the child of Soviet ‘nationalities policies’, Baberowski states. Meanwhile, Jens Jessens deems the origins of Ukraine ‘artificial’. He considers Ukraine’s existence as an independent state the product of ‘a misunderstanding within the former Soviet nationalities policy’. As a matter of fact, Soviet nationalities policy played a prominent role ‘in view of the extremely heterogeneous national composition of the Soviet Union [...] as well as of the immense development gaps between regions,’ as Gunnar Wälzholz confirms.[56] The often contradictory Soviet nationalities policy had two long-term, interlinked aims, Wälzholz points out. On the one hand, the aim was to prevent the disintegration of the formerly Tsarist empire through concessions to the nationalities as well as suppression of separatist tendencies. On the other hand, the societal modernization of the culturally diverse nationalities of the empire was seen as a precondition for the merging of the different cultures. The end goal was the cultural integration of the various nationalities into a ‘Soviet Nation’ (Russ.: Sovetskaia natsiia). The Bolsheviks interpreted nationalism as a manifestation of the class struggle within nations. Through the victory of socialism, classes were supposed to disappear and the peoples of the Soviet Union would merge with one another.[57] The conflictive principles of the promotion of nationalities[58] (korenizatsiia) on the one hand, and their assimilation on the other, were applied depending on political requirements – from cultural promotion (language, history[59]), deportation of whole nations (Crimean Tatars, Chechens) to the liquidation of national elites on charges of ‘bourgeois nationalism’ (Ukraine).

Ukraine is not one of those ‘artificial nations’ created by the Soviet nationalities policies of the 1920s. But Ukraine may – arguably – be defined as a nation ‘in the making’. It is a community in the process of being born. This process of ‘nation building’ has been accelerated via the Maidan movement and as a result of Russian aggression.

[hr][40] During and after WW I in Poland a Ukrainian nation was considered a „German invention“. See: Hans-Ulrich Stoldt / Klaus Wiegrefe, “Befreiungstruppen basteln (Creating liberation troops). Interview with the Historian Frank Golczewski about German attempts, to support Ukraine against the Tsar,” Der Spiegel, No. 50, 2007, 10.12.2007 <http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-54230886.html>.

[41] Matthias Nass, “‚Putins Vorgehen ist verständlich‘. Helmut Schmidt über Russlands Recht auf die Krim (‚Putin’s way of acting is understandable‘. Helmut Schmidt on Putin’s right to Crimea...),“ Die Zeit, No. 14, 27.03.2014 <http://www.zeit.de/2014/14/helmut-schmidt-russland>.

[42] Jens Jessen, “Teufelspakt für die Ukraine (Pact with the Devil for Ukraine),” Die Zeit, No. 14, 28.03.2014. <http://www.zeit.de/2014/14/ukraine-unabhaengigkeit>.

[43] The Fevral’skaya revolutsiya started on February 23 (Julian calendar) / March 8 (Gregorian calendar).

[44] At the initiative of the Fellowship of Ukrainian Progressivists (Tovarystvo Ukrayinskykh Postupovtsiv)

[45] In its „I. Universal“, dated 23 June 1917, the Central Council demanded the autonomy of Ukraine within a federalized Russia. By its “II. Universal”, dated 16 Juli 1917, the General Secretariate renounced a unilateral declaration of independence.

[46] Peace treaty signed March 3, 1918, called Brotfrieden in German (“peace for bread”).

[47] The German occupation authorities dissolved the Central Council and on 29 April 1918 founded the Ukrainian State (Ukr.: Ukrayins’ka Derzhava), also called The Hetmanate (Ukr.: Het’manat), and appointed General Pavlo Skoropadsky as Hetman (in power until December 2018).

[48] Jörg Baberowski, “Zwischen den Imperien (Between Empires),” Die Zeit, No. 12, 13 March 2014; <http://www.zeit.de/2014/12/westen-russland-konflikt-geschichte-ukraine>.

[49] Anna Veronika Wendland, “Offener Brief an Prof. Jörg Baberowski, HU Berlin, zu seinem Artikel 'Zwischen den Imperien‘ in der ZEIT Nr. 12/2014 vom 13.03.2014, S. 52,“ Euromaidan Berlin, 25 March 2014 <euromaidanberlin.wordpress.com/2014/03/25/ein-offener-brief-von-der-historikerin-anna-veronika-wendland/>. Baberowski argues, that in the cities of Eastern and Southern Ukraine’s the national idea had limited appeal, because they were predominantly inhabited by Russians and Jews. The Ukrainian peasants, who moved into the cities, he argues, did not feel their linguistic assimilation to be tragic.

[50] Franziska Davies, “Die Ukraine – eine künstliche Nation? (Ukraine – an artificial nation?),“ Der Freitag, 1 April 2014 <https://www.freitag.de/autoren/franziska-davies/die-ukraine-eine-kuenstliche-nation>.

[51] Anna Veronika Wendland, “Offener Brief an Prof. Jörg Baberowski.“

[52] Ibid. See also: Idem, “Für ein neues Land,” Der Freitag, No. 15, 10 April 2014 <https://www.freitag.de/autoren/der-freitag/fuer-ein-neues-land>.

[53] Baberowski, “Zwischen den Imperien.“

[54] Idem, Verbrannte Erde. Stalins Herrschaft der Gewalt. München (C. H. Beck Verlag) 2012.

[55] Idem, “Zwischen den Imperien.“

[56] Gunnar Wälzholz, Nationalismus in der Sowjetunion. Entstehungsbedingungen und Bedeutung nationaler Eliten. Osteuropa-Institut der Freien Universität Berlin, Arbeitspapiere des Bereichs Politik und Gesellschaft, Heft 8 / 1997.

[57] The two-track nationalities policy was ideologically justified with Lenin’s dialectic doctrine, according to which the “promotion of the free development of the nationalities leads in the end to their natural amalgamation”. The “Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia” ( Russ.: Deklaratsiia prav narodov Rossii) was promulgated on November 15 (Gregorian calendar) / November 2 (Julian calendar) 1917 by the Bolshevik government and signed by Vladimir Ul’yanov / Lenin, chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars) and Iosif Dzhugashvili / Stalin (People’s Commissar of nationalities). See: “Deklaratsiia prav narodov Rossii, 2(15) noiabria 1917 g.," in: Sbornik dokumentov “Obrazovanie SSSR”, Moskva, 1949, pp. 19-20 <http://www.pravo.by/print.aspx?guid=5741>.

[58] The „nationality“ (Russ.: natsional’nost’) of Soviet citizens was documented in identification cards, and passed on from parents to children. Thus “nationality” was a “biological category” (Gunnar Wälzholz) which promoted ethnical segregation.

[59]„The Bolsheviks organized the multinational empire according to ethnic principles, founded republics [...] designed (national) languages and national histories”, states Baberowski. Wälzholz clarifies the purpose of this order: “The territorialization of ethnicity was an instrument of control”. And Wälzholz does not ignore the perfidious manner, how Stalin drew the boundaries. As a consequence of the deliberate “incongruence of ethnos and territory,” national minorities with competing territorial claims were systematically created, in order to control these nationalities.

By the 19th century, a Ukrainian national consciousness had developed under Central European influence in what is today’s western Ukraine – which was annexed by the Soviet Union as part of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 23 August 1939. The national sentiment of Ukrainians living in what was then eastern Poland was radicalized by inter-war resistance to repression by Poland, which had re-emerged as an independent state after World War I (Treaty of Versailles). Stalin justified the invasion of eastern Poland by the Red Army on September 17, 1939 – just 17 days after the beginning of Hitler’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939 – as a campaign to ‘liberate’ Ukrainian (and Belarusian) brothers ‘from the Polish yoke’.[60] As a result of Soviet annexation of eastern Poland, all Ukrainians[61] were united for the first time in history into a single –although only pseudo-autonomous – State, the ‘Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.’ ‘Stalin realized the dream of Ukrainian nationalists’, as Jörg Baberowski has stated markedly.[62]

The radical nationalism in present-day western Ukraine has its roots in the mid-20th century era, namely:

- in the period between the two world wars, when the indisputably fascistoid Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (Orhanizatsiya Ukrains’kykh Natsionalistiv / OUN) fought for independence from Poland;

- in the hidden confrontation between the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (Ukrains’ka Povstans’ka Armiia / UPA) and the Polish Home Army (Armia Krajowa) during World War II;

- in the resistance of the UPA against the German Wehrmacht and SS during World War II, after the OUN’s initial collaboration with the Nazis in the mistaken belief that German troops had come as liberators;

- in the UPA’s struggle against the Red Army and NKVD[63] troops during World War II;

- in the resistance of the UPA against the NKVD for a further ten years, after the end of World War II.

Ukrainian nationalism was born in times of repression. It has mostly remained defensive and not aggressive in character, unlike imperial Russian nationalism. Today, mainstream Ukrainian nationalism should be see as an emancipatory movement rooted in notions of ‘liberation,’[64] and as reminiscent of the German National Movement before March 1848 (Vormärz). Much of it is therefore compatible with liberal democracy. Yet, in Brussels and Berlin, it is not always appreciated that the nationalism of a ‘young nation’ with an unstable national identity – particularly in times of aggression from within and from outside – cannot be equated with the anachronistic, xenophobic nationalism in the countries of Old Europe.

Owing to the growing weight of votes cast for Euro-skeptic parties in EU member states, European politicians are becoming highly sensitive to any symptoms of nationalism. This makes them receptive to Russian propaganda, according to which ‘fascist’, xenophobic and anti-Semitic forces exert political influence in Kyiv. In reality, ‘Ukrainian Fascism’ is a Russian bogey, as the results of the presidential elections on 25 May, 2014, and the parliamentary elections on 28 October, 2014, demonstrated. The presidential candidates of the two radically nationalist parties, ‘Freedom’ and ‘Right Sektor’, Oleh Tiahnybok and Dmytro Yarosh respectively, obtained together less than 2% of the vote. In the 2014 parliamentary elections, the Freedom Party, which had gained over 10% of the vote in Ukraine’s previous parliamentary elections in October 2012, failed to clear the 5% hurdle. Meanwhile, the hyped ‘Right Sector’ obtained less than 2 % of the vote.

It is true that, on the Maidan, historical symbols from the era of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army were revived. These symbols, which appear hopelessly out-of-date to West European audiences, were readily accepted by many protesters who had previously not been susceptible to nationalistic slogans. The chant ‘Glory to Ukraine!’ (‘Slava Ukraini!’), answered with the refrain, ‘Glory to the Heroes!’ (‘Heroiam slava!’), became commonplace among patriotic Ukrainians during the Maidan protests.[65] When people shouted this slogan on Maidan in the winter of 2013-2014, it was not yet suspected that shootings in Kyiv, and a war in the east of the country would soon be producing a new generation of present-day heroes (see video, where over 200 000 people on Maidan chant "Glory to Ukraine"):

The Ukrainian patriotism sparked by the Maidan protests mobilized the willingness to defend the peacefully gained independence of the country by force of arms. Former ‘Defenders of Maidan’ spontaneously organized themselves into volunteer military battalions. Many have since been deployed to the fighting on the ‘eastern front’, where they risk their lives on a daily basis. Equipment is often donated by relatives and friends. Although nobody preaches openly that it is ‘noble and honourable to die for the Fatherland’,[66] a certain glorification of the fight against Russian mercenaries is tangible among politicians.

On the other hand, there is evidence of massive draft evasion. As in the year 1939, when the French asked the classical rhetoric question: ‘Mourir pour Dantzig?’,[67] there is no universal inclination, even in particularly patriotic regions of western Ukraine, to ‘die for the Donbas’.[68] Russia’s President Putin has personally extended his protecting hand towards Ukrainian draft dodgers.[69] In order to bolster fighting spirit, the Ukrainian government has felt compelled to raise soldiers’ pay and to offer rewards for the destruction of enemy armament.[70] Ukraine’s patriotic civil society continues to demonstrate an extraordinary willingness to ‘support the troops’. A great number of volunteer organizations throughout the country collect donations for the soldiers serving on the front lines.

Ukraine is now in the process of writing itself its own history. In the new schoolbooks, the term ‘Great Patriotic War’ (Russ.: Velikaia Otechestvennaia Voina), which was reintroduced by the Ukrainophobic Minister of Education Dymtro Tabachnyk during Yanukovych’s reign, will be replaced by the term ‘Second World War’. During his term in office, Tabachnyk pursued the re-Sovietization of Ukrainian history – including the publication of a joint Russian-Ukrainian history textbook.

Read also: The “Great Patriotic War” as a weapon in the war against Ukraine

The date 14 October has been declared Defenders of Ukraine Day (Den’ Zakhysnyka Ukrainu) by presidential decree. Defenders of the (Soviet) Fatherland Day (Russ.: Den Zashchitnika Otechestva), which was previously marked annually on 23 February, has duly been cancelled. The choice of the date 14 October has particular historical significance as:

- it is Ukrainian Cossack Day (Den’ Ukrains’koho Kozatstva), a holiday introduced by President Leonid Kuchma in a bid to acknowledge the historical role of the Zaporozhian Cossacks in the development of Ukrainian statehood;

- it is a traditional Orthodox Christian holiday: The Day of the Protection of the Most Holy Mother of God (on this day the Cossacks would traditionally elect their Ataman);

- it is the anniversary of the foundation of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army.

Read also: New October 14 ‘Day of Defender of Ukraine’ holiday marks break with Soviet past

Another day has been set aside to mark the country’s modern pro-democracy breakthroughs. 22 November is now Ukraine’s Dignity and Freedom Day (Den’ Hidnosti ta Svobody), marking the anniversaries of the 2013 Euromaidan protests and 2004’s Orange Revolution. Meanwhile, 22 January will continue to be celebrated as National Unity Day (Den’ Sobornosti Ukrainy) in remembrance of the proclamation of the unification of the Ukrainian People’s Republic and the West Ukrainian People’s Republic which took place on 22 January, 1919.

Unlike nationalism in the member states of the European Union, Ukrainian nationalism is not anti- but pro-European. For the vast majority of the population in today’s Ukraine, national self-assertion does not conflict with pro-European sentiment. This feeling of belonging to Europe was articulated impressively during the Euromaidan movement. As a future member of the European Union, a union sui generis of nations (motto: ‘In Varietate Concordia’, ‘Unity in Diversity’) Ukraine could hope to preserve and develop its cultural identity, particularly, concerning the Ukrainian language. As a member in Putin’s Eurasian Union, Ukraine would not escape a renewed wave of Russification. Ukraine can only hold its own as a nation from within the European Union. With the help of the European Union, Ukraine will emerge from the war with Russia – possibly territorially amputated – as a ‘European nation’ with a consolidated national identity and a functioning democracy.

[hr]* The English translation was language-wise edited by Peter Dickinson. Andreas Umland helped preparing the final version published here.

[60] On 22 October 1939 Moscow staged „elections“ to a „People’s Assembly of Western Ukraine“. According to official statements the candidates of the „Block of Workers, Peasants and Intellectuals” obtained 90 % of the vote. On 27 October 1939 the “People’s Assembly of Western Ukraine” proclaimed the “Accession of Western Ukraine to the USSR”. The annexation of Eastern Poland by the Soviet Union – and the expulsion of the Polish population – was accepted by the presidents of the Western victorious powers Harry S. Truman / USA and Winston Churchill / Clement Atlee / GB) at the Potsdam conference on 17 July – 2 August 1945.

[61] With the exception of the Ukrainians living in the Kuban region in Southern Russia.

[62] Jörg Baberowski, “Zwischen den Imperien.“

[63] NKVD – People’ Commissariate for Internal Affairs (Narodnyi komissariat vnutrennikh del), predecessor of the KGB (Komitet gosudarstvennoi bezopasnosti).

[64] Konrad Schuller, “Die ukrainische Opposition: Ohne Wolfsangel (The Ukrainian Opposition. Without the Wolf’s Hook),” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 10 February 2014 <http://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/ausland/europa/die-ukrainische-opposition-ohne-wolfsangel-12793039-p2.html>.

[65] From among more radical protestors could also be heard the such clearly nationalist slogans as: „Glory to the Nation – Death to the Enemies!” („Slava natsii – smert’ voroham!“) and „Ukraine above all!” („Ukraina – ponad use!“)

[66] „Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori”, Horaz, Carmina 3,2,13.

[67] Title of a controversial article by Marcel Déat in the French newspaper L'Œuvre in Mai 1939.

[68] “Biriukov vozmutilsia pervymi resul’tatami vypolneniia plana mobilizatsii (B. upset by the first results of the implementation of the mobilization plan),” Ukrainskaia pravda, 27 January 2015; <http://www.pravda.com.ua/rus/news/2015/01/27/7056588/>. Yuri Biriukoy is advisor to the president.

[69] “Vstrecha so studentami Gornogo universiteta (Meeting with the students of Mining University),” Prezident Rossii, 26.01.2015 <http://www.kremlin.ru/news/47519>.

[70] Website of the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine, 28 January 2015; <http://www.mil.gov.ua/news/2015/01/28/za-znishhennya-vijskovoi-tehniki-protivnika-uchasniki-ato-otrimuvatimut-dodatkovu-vinagorodu--/>.