When does Russia’s economy finally collapse?

You’ve been asking this for three years. Western leaders keep saying sanctions are working. The numbers keep getting worse for Moscow. And yet Russia keeps fighting.

The budget deficit quadrupled. Oil revenues dropped from half the federal budget to barely a fifth. The emergency fund shrank from $145 billion to $40 billion. By every metric, Russia should be breaking.

But Russian missiles keep launching. Troops keep advancing. Moscow shows no sign of stopping.

So what’s actually happening? Where is the money coming from? And when—if ever—does the economic pressure actually work?

“Now, the situation is critical,” says Volodymyr Vlasiuk, PhD in economics, CEO of the state enterprise Ukraine Industry Expertise, who has tracked Russia’s war economy since the invasion began. “They cannot finance the war of the present intensity for a long time.”

Russia has one escape route. It runs through Beijing.

The balance sheet problem

“Every economy has its own specific, but we should always look for balance between expenses and revenue,” Vlasiuk explains. “When this balance is distorted, consequences will follow.”

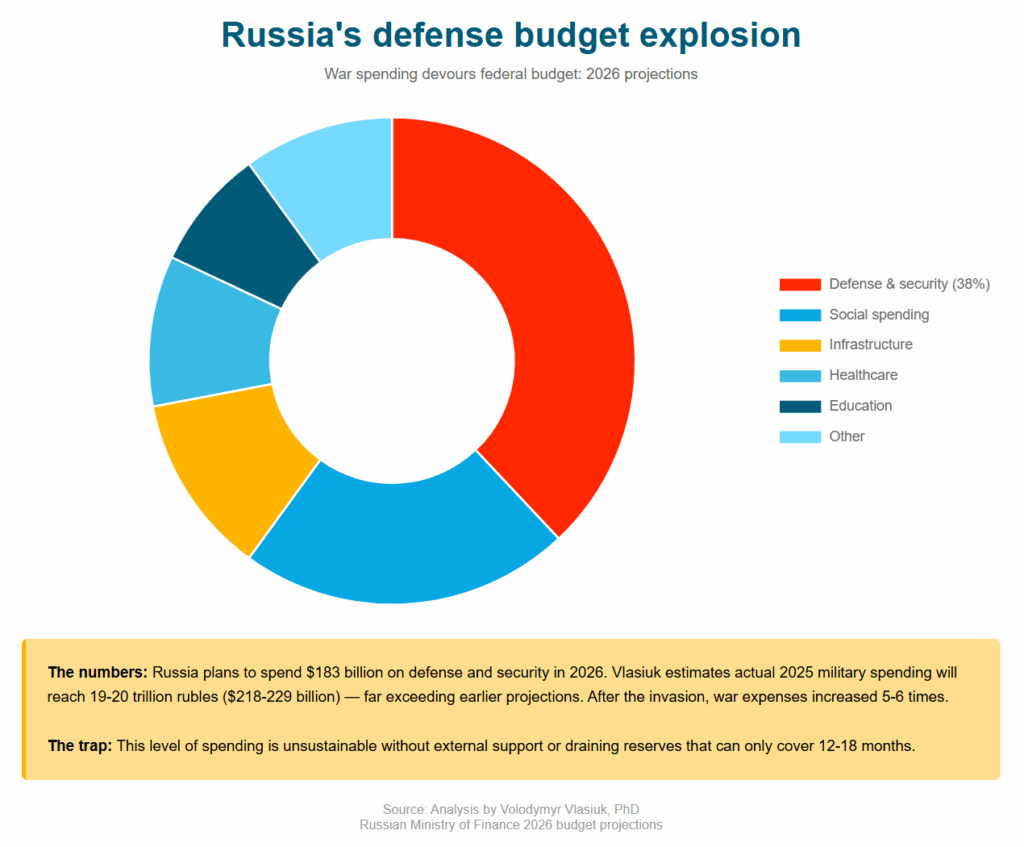

After Russia launched its full-scale invasion, war expenses increased five to six times. Russia plans to spend $183 billion on defense and security in 2026—38% of total federal expenditures. This year, Vlasiuk estimates military spending will reach 19-20 trillion rubles ($218-229 billion), far exceeding earlier budget projections.

Meanwhile, Russia’s revenue streams are drying up.

According to Vlasiuk, export revenues from oil and oil products dropped 12% in the first six months of 2025. This creates what the economist calls “an unfavorable combination of factors.”

The inflation nobody talks about

Official Russian inflation (9.1%) versus real composite index calculation (25.6%). Chart: Volodymyr Vlasiuk analysis, Russian Central Bank, Euromaidan Press

Russia’s official inflation rate is 9.1% as of August 2025, down from 9.8% the previous month. Alternative calculations show 25.6%.

The gap reveals the effectiveness of Western sanctions—and why patience matters. Russia can distort some economic indicators, such as official GDP growth and inflation data. Central Bank chair Elvira Nabiullina recently adjusted rates under intense pressure from industrial lobbies despite persistent inflation.

“They cannot falsify the level of money printing, the broad money base,” Vlasiuk notes. “At the same time, they can and do falsify inflation.”

Vlasiuk calculated real inflation using a composite index tracking consumer and industrial prices. He expects it to reach 25.6% in 2025.

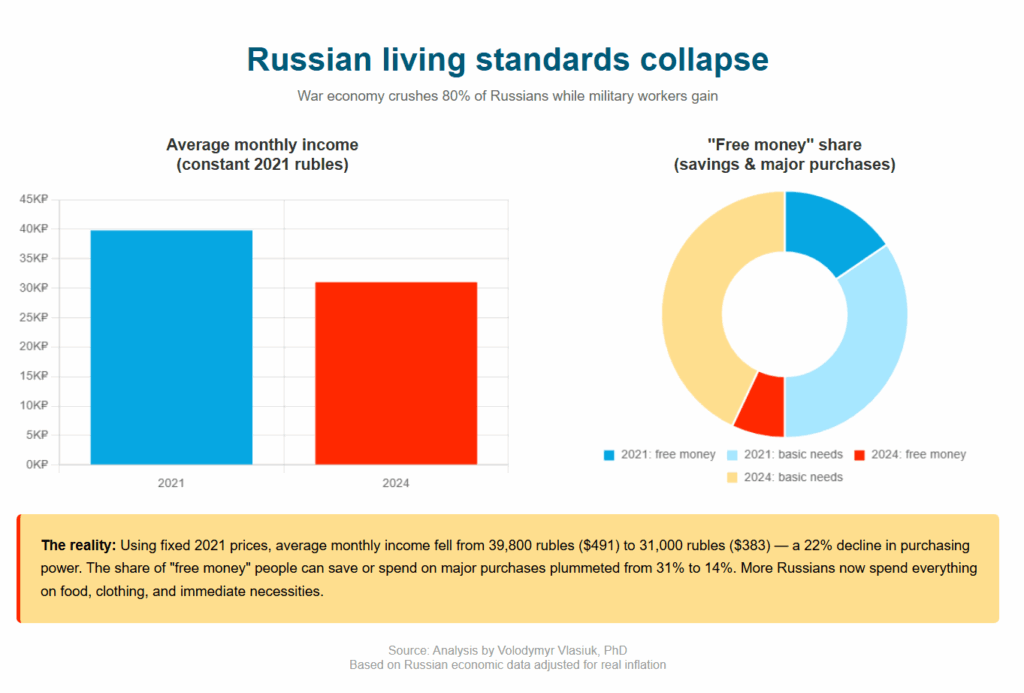

Russian living standards are collapsing. Using fixed 2021 prices, average monthly income per capita was 39,800 rubles ($491) that year. By 2024, it had fallen to 31,000 rubles ($383) in constant prices—a figure Vlasiuk derived from analysis.

The share of “free money”—what people can save or spend on major purchases—plummeted from 31% to 14%. More Russians now spend everything on food, clothing, and immediate necessities.

“We can observe the dramatic decrease in living standards in Russia,” Vlasiuk says.

This is pressure from sanctions and huge military expenses, translating into domestic pain. So far, it’s a slow burn, but the risk of transforming it into a quick fire rises daily.

The 20/80 divide

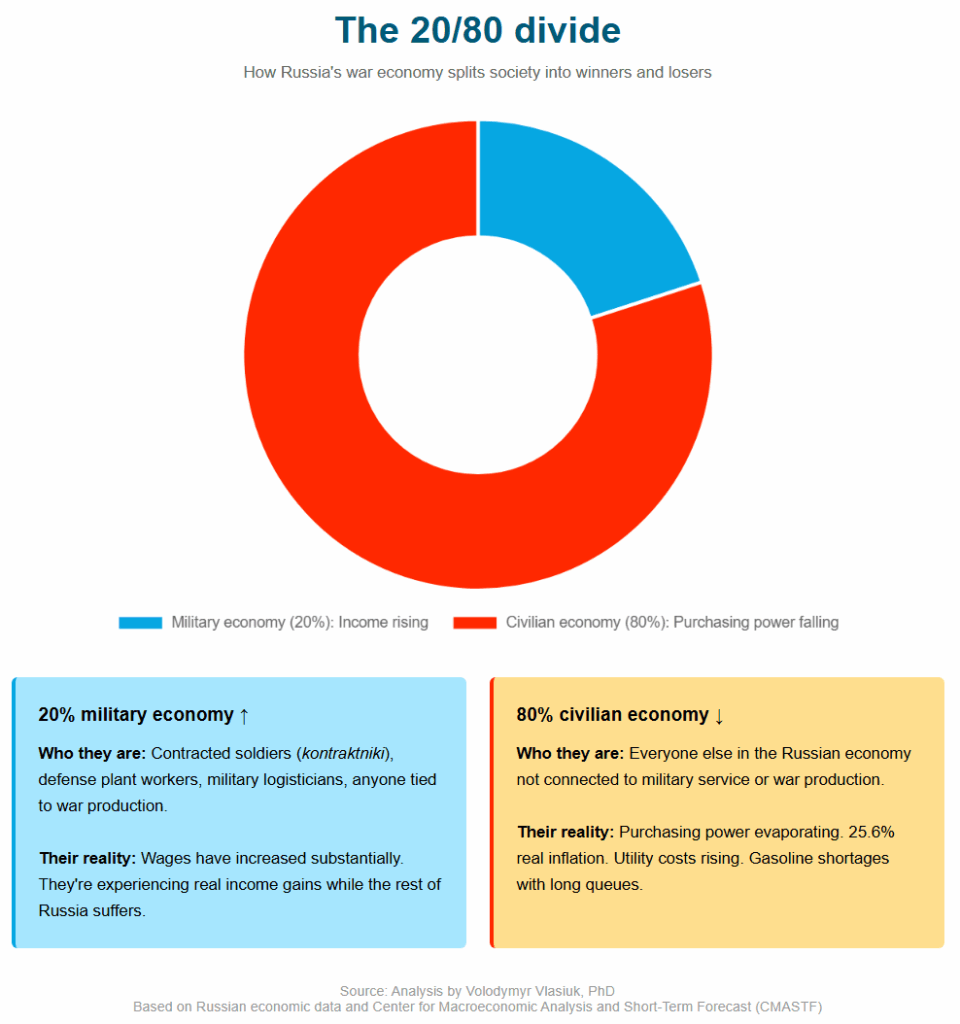

As Vlasiuk explains, there’s a divide in Russian society: about 20% of Russia’s population earns income connected to military service or war production, and their wages have increased substantially.

Who are they? So-called kontraktniki—contracted soldiers fighting in Ukraine—workers at defense plants, logisticians. In short, anyone tied to the military economy. These Russians are experiencing income gains.

The other 80% are watching their purchasing power evaporate.

Inflation on essential goods for everyday consumption hit particularly hard, Vlasiuk notes, pointing to data from the Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-Term Forecast (CMASTF), an analytical agency close to the Russian government. Utility costs are rising.

Ukraine’s strikes on Russian fuel infrastructure have created gasoline shortages, and long queues of cars waiting to fill up have become common.

This creates social tension that Putin must manage. “It’s not the time of Stalin’s Soviet Union,” Vlasiuk observes. “Russian people have cars and other property, have some standard of living. To refuse this completely is difficult, even with ideological impulse.”

Private sector in decline

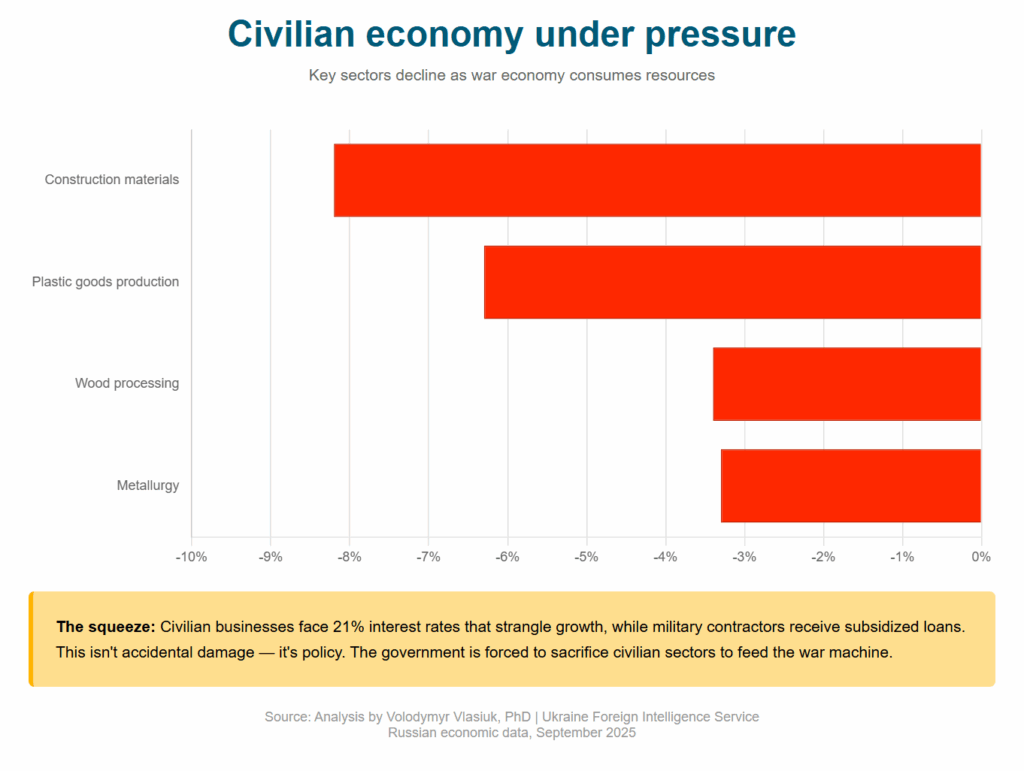

Fresh intelligence from Ukraine’s Foreign Intelligence Service shows how thoroughly the war economy has consumed civilian business. The number of registered enterprises dropped to 3.17 million by September 2025—the lowest since 2010.

Business “mortality” exceeded new registrations by 1.5 times in early 2025, marking the first time since sanctions began that more companies died than were born.

Russia’s tax service systematically liquidated over 100,000 companies in 2024, targeting trade, construction, and manufacturing firms that compete with defense industries for workers and resources.

According to Vlasiuk’s analysis of Russian economic data, specific sectors tell the story. Wood processing fell 3.4%, plastic goods production dropped 6.3%, construction materials declined 8.2%, and metallurgy slipped 3.3%.

Why? Civilian businesses face 21% interest rates that strangle growth, while military contractors receive subsidized loans. This wasn’t accidental damage—it was policy, Vlasiuk explains. The government is forced to sacrifice civilian sectors to feed the war machine.

Unemployment dropped to 2.2%, and 3.8 million Russians now depend on defense-related employment—figures Vlasiuk cites as evidence of the economy’s militarization.

Stagflation arrived in 2023

“There is a discussion whether there is stagflation or not,” Vlasiuk notes. “We are completely sure stagflation has come to the Russian economy.”

Stagflation—a combination of stagnation and inflation—happens when an economy stops growing while prices keep rising, creating the worst of both worlds. Russia’s economy has essentially flatlined at 0.4% growth. But prices keep jumping: 8.1% officially, 25.6% in reality, by Vlasiuk’s calculation.

When growth stalls but inflation accelerates, governments face an impossible choice: fight inflation (which kills jobs) or fight unemployment (which feeds inflation).

“Real stagflation in Russia started not even now, but in late 2023,” Vlasiuk says, based on his real inflation calculations.

Trending Now

Stagflation creates a vicious cycle: slowing production, job losses, decreased living standards, and falling tax revenues. Which brings us back to the budget problem.

The deficit nobody can hide

Russia’s budget deficit hit 4.2 trillion rubles ($48.2 billion) in the first eight months of 2025—four times higher than the previous year. This number is hard to falsify.

“The question is how they will cover the budget deficit at the end of this year,” Vlasiuk explains.

Russia faces three options, and only one is sustainable.

- Printing money through government bonds would inject rubles into an economy already suffering 25.6% real inflation. “But this money will be at the market early in the next year, and this will contribute to inflation, which is now at the galloping level,” Vlasiuk warns. This accelerates the crisis rather than solving it.

- Draining reserves means tapping the remaining $40 billion National Wealth Fund. “Maybe they will use half of it—let’s say 20 billion dollars in yuan, which roughly equals 2 trillion rubles ($24.7 billion), something like this,” Vlasiuk calculates. “You can compensate only part of the budget deficit.” This buys roughly 12-18 months—then the problem returns, worse than before.

- Seeking external support is the only path that doesn’t lead to a worse crisis. “Maybe they will repeat what they did last year,” Vlasiuk suggests—referring to Russia’s combination approach of printing money, tapping reserves, and creative accounting that covered deficits in late 2024. “But the situation is critical now.”

Analysis from Navigating Russia reveals another pressure point: Russia has secretly forced banks to lend $210-250 billion to military contractors—shadow financing matching the official defense budget. This hidden debt pushed the banking system toward crisis.

After roughly 12-18 months, Moscow faces a binary choice: get significant economic support from abroad, or reduce military spending, which means reducing the war’s intensity.

The Beijing conundrum

Vlasiuk outlines two theoretical escape routes. Russia could receive sanctions relief—“very unfavorable for Ukraine”—or secure macroeconomic aid from China.

The Ministry of Finance of Russia has asked China for such support, Vlasiuk notes.

China refused.

Yet both options remain possible—sanctions can be relieved, and China may change its stance. Vlasiuk notes that the world isn’t black and white, and circumstances can change.

But for now, both exits are blocked, economic pressure continues building, and Putin must manage the domestic political consequences.

Pressure from the regions

Regional budgets cut by 4 trillion rubles in 2025, nearly half their funding. Chart: Volodymyr Vlasiuk analysis, Russian Ministry of Finance, Euromaidan Press

Regional elites are already starting to feel the squeeze, as local budgets have been slashed by 4 trillion rubles ($49 billion)—nearly half their funding.

“Putin has some sort of pressure from the regional elite,” the expert observes. “Maybe mild pressure, but they are asking him to stop the budget cuts.”

The whole Russian budget exceeds 66 trillion rubles ($815 billion at the current exchange rate of 81 rubles/dollar), Vlasiuk explains—almost 43 trillion federal, 23 trillion regional. “In 2025, the regional budget expenditures were reduced by almost 4 trillion.”

Putin must maintain calm in major cities, “because the destiny of Russia is decided in Moscow and Saint Petersburg,” but completely depriving regions of funding is still impossible, “even in Russia now.”

This creates political pressure on Putin from below—from the governors and regional business elites needing funding to maintain their territories’ stability.

It’s another sign the trap is tightening, even if regional elites can’t force Putin’s hand on the war.

Carnegie analyst Aleksandra Prokopenko calculates the dilemma starkly: Russia cannot demobilize without mass unemployment, cannot continue the war without fiscal ruin, and cannot maintain current spending without draining national reserves.

Prokopenko expects “the fifth crisis on Putin’s account” regardless of battlefield outcomes.

What the timeline means

So, when does Russia’s economy collapse?

Vlasiuk’s analysis is explicit: Russia’s economic trap is undeniably real but won’t snap shut overnight. “I cannot say when the point will be for the crushing of the Russian economy,” he admits. But the math provides some clarity.

Russia is surviving—but sinking deeper with each passing month.

That leaves two paths:

Path 1: External rescue: Russia’s timeline extends indefinitely if China reverses its position or Western sanctions weaken. But the economic trap stays open. Putin avoids the choice between reducing the war and economic catastrophe. Vlasiuk notes this would be “very unfavorable for Ukraine.”

Path 2: Reduce the war: Without external support, Russia cannot sustain its current war intensity much longer. Regional budget cuts, collapsing living standards, and banking system stress create mounting political pressure. Putin would need to reduce military spending, which means reducing the war’s intensity.

The race that determines Ukraine’s fate:

- Can Ukraine hold defensive lines for 12-18 months?

- Will the West maintain military support that long?

- Will external circumstances shift before Russia’s options narrow?

- Will economic pain translate to political pressure that Putin can’t ignore?

For Western publics and decision-makers, this means accepting several realities simultaneously.

First, sanctions are working—the economic distortions and fiscal crisis are real and worsening. The payback for the war has already come in the form of worsening socio-economic indicators. Western support has created genuine pressure on Moscow, and time plays seriously against the Russian economy.

Second, the timeline matters. The $40 billion in reserves alone cover perhaps six months at current deficit rates. With controlled money printing and the existing $210-250 billion in shadow loans forcing banks to finance military contractors, Moscow can stretch that to 12-18 months. But Russia isn’t solving the problem—it’s buying time while the crisis deepens. Each month, inflation accelerates, living standards collapse faster, and regional pressure mounts. The trap tightens with every delay.

“I cannot say when the point will be for the crushing of the Russian economy,” Vlasiuk emphasizes. But without external rescue, that point arrives within 12-18 months.

Third, battlefield victories won’t come from waiting for the Russian economy to collapse. Ukraine needs weapons, ammunition, and sustained support to achieve military success before Russia either gets external support or breaks through Ukrainian defenses.

Finally, Ukraine’s military resistance, together with Western support and sanctions, has already remarkably exhausted the Russian economy.

The trap tightens daily. Whether it forces a binary choice before Ukraine’s defenses buckle depends largely on how long the West maintains support and whether external circumstances change.