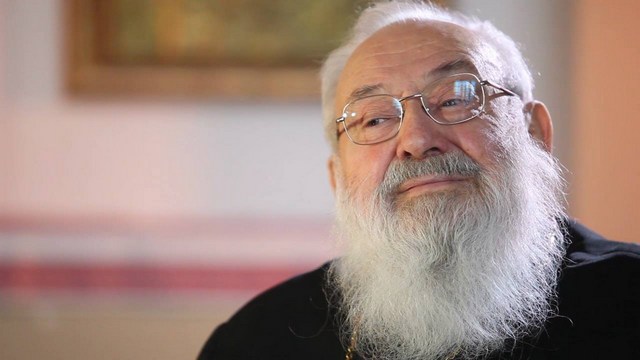

Cardinal Lubomyr Husar shares what the events of the winter of 2013-2014 mean for him, participating in a project of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory and the Fund for the preservation of the history of the Maidan, “Maidan: an oral history.”

Can it be said that the members of the Initiative Group, “First of December”, of which you are a member, in some manner prepared the Maidan?

Truthfully, no, we did not prepare the Maidan, our goal was to change the very materialistic motivation behind everything the government was doing, and by extension in the life of the nation, in order to make spiritual goals a priority.

On the first of December, 2011, representatives from three of our traditional churches made the following query: twenty years have now passed, but why has there not been any progress? The answer is that we base our reason for living on materialistic values, the same standards as those of Soviet society. We took our name from that day, the first of December.

We set a goal for ourselves of transforming our common life, wherehuz the concept of truth, good, justice would not merely remain at the theoretical level, but be something practical. We likewise began to work on a charter, which is what we called it. Later, this charter was ratified during a round table discussion.

The topics of discussion included problems concerning the mass media, communication, and education. In this manner we were able to establish a context within which we could respond to the Maidan and its participants, who came from all age groups, and in whose hearts were harboured certain values. These values later would come to be known as the revolution of human dignity.

The Charter of the free person proclaims that a human being is not the slave or captive of any government or group of people. Consequently, a person not only has rights, but also a mission, a responsibility to be mutually respectful to other human beings.

This is the way in which I would say that we were involved in any preparation of the Maidan, but not in the actual manner in which it developed, or calling people, calling the nation, together.

Where did the Initiative Group meet?

Most of the time the gathering was in the offices of the Hryhorii Skovoroda Institute of Philosophy, or at Myroslav Popovych’s, and also at the Kyiv Mohylianska Academy. Members of our Initiative group tried their best to organize the type of round tables at which there would be direct meetings between the government and representatives of the Maidan. We didn’t have any official status, but we were kept very busy with our efforts.

What sense of foreboding did you experience as the crowds were forming on Independence Square after the refusal of the Azarov government to sign the association agreement with the European Union?

At one meeting where I was present, Azarov spoke for a very long time, but he was talking very fast and very emotionally, and speaking in Russian. I really don’t understand Russian all that well, and then when someone speaks quickly, I barely understood him. My impression was that in his mind the Maidan was over, and he was trying to justify why it was not a good idea to try it.

Nonetheless we had this unsubstantiated hope that the president still might go and sign it.

He did go, but he came back empty handed. That’s when the crowds started to gather, to show their categorical disagreement with what the president and the government had done. It was nearly impossible to foresee what would come next.

With the passing of time, it became clear that there was this desire for some kind of fundamental change, one that didn’t merely change individuals, but the entire system. The government was still firmly established. There was a general trust of the government, but that good will eroded with each passing day, once their conduct became better known and they created the Anti-Maidan, and seeing how the Berkut acted, culminating in the shootings. Any confidence in such a government was simply impossible.

Several different political factions had the intention of co-opting this popular movement to benefit their own agenda. I remember hearing the speeches of individual politicians, and could tell that they weren’t quite certain what direction they should be taking with their statements.

What were your news sources for the events of the Maidan?

Much of it came from the people who spoke during the meetings of the Initiative group: participants spoke of their experiences. In addition, there were priests who visited the Maidan, and nuns as well, and in general people spoke of their impressions. There was a lot of detailed information on the radio, which I listen to, since I no longer am able to read.

And what I find interesting: the Maidan itself began to speak.

I was fascinated by the development of the structure of the Maidan, and how those who claimed to speak on behalf of the Maidan actually did represent the thoughts of the Maidan. Everything was spontaneous, and everything developed slowly, in a completely natural fashion. I recall that on Sundays there would be one hundred thousand people, if not more. I think this bothered the government. You know what I mean, you can execute a hundred people, but a hundred thousand is more difficult.

I was very interested in learning whether or not this popular movement would be able to speak with one voice and if its leaders would speak with authority. But it didn’t develop that way; it was completely spontaneous. Further, at the beginning there was no identifiable central committee as the general organizer. The way it grew was very fascinating. With regard to its start, I would say it had not been planned in advance, and not prepared in detail when it started, and nonetheless it developed a very distinctive identity. It was the complete opposite of the French Revolution when all they were doing was killing one another. The Maidan presented itself as a complete unity. Even when there were a hundred thousand people present, whenever they were singing or reacting to something, they responded together.

In your own mind, how do prioritize the most important events of the Maidan?

The singular event was the beatings of students by the Berkut on November 30. I am still convinced what should be done, and even encourage the establishment of a special commemoration for this day.

The events surrounding the Heavenly Hundred are more tragic in both the numbers and methods, yet for some reason, the events from the night of the 29th to the 30th have left an impression that remains strong in my mind. This is in no way to say that I am trying to forget what was to follow, because that was the blow that would start a chain reaction, including the flight of the president. It was such an unequivocal moment that set the tone for everything that followed.

Why do you think people resolved to take such radical action, without the fear of death?

Their experience was similar to being on the front lines. I myself have never been at the front, but one can very well imagine. At that moment when you are face to face with the enemy, you are no longer thinking about death. I think it was similar here. There was such an explosion, a reaction that reverberated throughout Ukraine, the government, and the people.

The events that occurred on Hrushevskyi and Instytutska streets, these were already the kind of incidents that were more dramatic, mobilizing the people to action. As an example, the construction of the barricades was no less a sign of protest. All this was important, but it was not the essence of the Maidan. Here is some of what we will always remember: the chapel, crosses, the 30th of November, and later, the renaming of the streets, each of these details. All of them are part of the fabric of the Maidan.

Fundamentally, however, it seems to me that the Maidan was an interior experience. People reached a concrete moment in time when they stated, “Enough!” As a reaction, it was happening in Kyiv, but it was also happening throughout Ukraine in various cities.

Soon people from other cities began arriving, to join those who were already here. The Maidan, then, is an interior revolution, and when that critical mass had been reached in the hearts of these people, its outward form was expressed.

The straw that broke the camel’s back was that moment when the government and the president denied what was happening and resisted it. It’s as if something was beginning to boil up inside, boiling, boiling, without being perceivable. Later, it erupted as the Maidan.

You know, probably no one could have expected what was about to happen.

I do think, however, that the government understood, and tried to resist, but by then they were already, how should I say, out of office.

The people did not exhibit any type of anger or hatred, but rather a certain desire, a profound longing for change, a radical turn towards that which today we call human dignity.

At the start of the events on Hrushevskyi Street, you and the other members of the Initiative group, “First of December” announced at a press conference your desire that the protests be kept peaceful.

That was our goal. We were trying to facilitate dialogue. The scenario of confrontation would be futile, where one side is shooting and the other throwing Molotov cocktails.

Looking back, it seems like such a naive effort to have expected the government to come to its senses.

People have told me that when a report would be made during one of these round tables about a certain number of deaths being reported, the president would be listening with quite a smirk on his face. People remembered that. In other words, there really was no one with whom to have a dialogue.

In the early days, there was a hope that the government would understand that they had to make some fundamental changes. All in all I think it was a very naive dream.

When Azarov would speak, he was revealing his subconscious conviction that none of this was to be taken seriously. It’s like this one Latin proverb, “You can sing all you want in the ear of a deaf person”…. Later, events would prove that to be the case.

What did the Maidan mean for the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church?

The Maidan had the same effect on the Church as it did on all other nationally conscious citizens. Our bishops and priests visited there, held services, conversed with the people, encouraged them, and supported them spiritually.

The close connection of the churches with the Maidan is something to be proud of, and we encouraged all of our clergy who were participating in the Maidan, to foster such relationships.

The events of the Maidan were experienced by different people in different ways. It seems to me that even among church goers there remain certain soviet styles of thinking and perceiving events. But that is disappearing, and in its place is emerging the mentality that we need to support.

In your opinion, why does it so often happen that Ukrainians resort to social protest?

Since the second half of the 18th century we have been living in a situation of occupation. What this means for today is that when the protests began against Yanukovych and his regime, he did not relate to them as to his own people. In return, his nation considered him to be a foreign government, not working for the good of the nation.

What followed is what I consider a completely natural reaction: whether it was, for example, the Austrian, or later the Polish occupation, especially the Bolsheviks, and also Hitler. They all made the conscious effort to destroy, and so the nation protested.

Why do you thing that UPA and OUN, this Ukrainian military organization, was created? It was a reaction against occupation. What form did this reaction that in the 1920s against the kolhosps and the Holodomor? There were over four thousand instances of insurgency in Ukraine. The villages were rising up against collectivization.

It is not in our nature to be so reactionary. In fact I would say that we are far too soft. Yet when we are provoked, then people react, which is a completely natural mechanism.

There must be a response. It’s a matter of self-preservation.

How has your assessment of the Maidan changed?

It seems to me that the Maidan underwent several different phases. The Maidan is first and foremost an outpouring from the depths and heart of the nation, lasting until Yanukovych fled the country. This is the best description of the real Maidan.

What now is to be our task? Those ideals that echoed throughout the Maidan must become incarnate in all areas of our life: whether at the Verkhovna Rada, the government, government ministries, the courts, business, and manufacturing. We must incorporate the spiritual values of the Maidan everywhere.

What would be the best way to teach future generations about the Maidan?

For the most part this is the task at hand today. It is the job of the government, of the society, and it goes without saying, educational institutions, as well as associations like the Initiative group. They will be the ones instilling in the future generation the spirit of the Maidan ideals.

It will be our responsibility to convey these ideals starting from the cradle, but then to continue once those now being born grow up; we must relate to the younger generation but not with the discredited soviet mentality.

For example, today we hear it said, “What good news that we see so many new faces there in the Verkhovna Rada.” The fact that they are new faces is no consolation to me. I ask myself: behind those new faces will we find new hearts?

The point is not to change one for another. We must exchange corrupt people for people who have integrity, who are true patriots, and whose heart is in the right place. This is what we need, but it is something at which we must work.

It is one thing to document how people lived during the Maidan, how they prepared their meals, that sort of thing. It is the idea that must be shown, to help young people see what actually happened because of the Maidan, why people their own age, students, became so engaged. Theirs was no a protest for the sake of being destructive; they were simply stating, enough, and it cannot be like this any longer. When the young people began to speak of what they were feeling, the older people, nationally conscious citizens, all those hundreds of thousands of people who attended the various assemblies, came forward to say that they were feeling the same way but didn’t have the same courage to do something about it.

When the youth took action, they followed with them.

Frankly, our hope is in these nationally conscious individuals. Those of us who are elderly cannot sit on the sidelines and say, let the young people take over. We must be there to help them understand and to kindle within them a desire.

What do you think of being called a moral authority?

Our Initiative group has this proposition: stop it already with the talk of moral authority, as if we were something we are not. We are ordinary people but we have experience, we are believers, and accept as the foundation of our lives the Christian principles of conduct.

We are not super-people. We are doing that in which we believe. Our perspective is somewhat more visionary than others. Now we need to increase our membership, since there aren’t very many of us compared with all the work that must be done.

It is society that must have the moral authority, without giving the impression that it is only attainable by special individuals. I am certain that there are more such people like us, and we just need to find them.

On its own, society does not adequately honour those people who live according to authoritative principles. Perhaps that is about to change. Who used to have the greatest respect? The Oligarchs with their money, they were heroes. It seems to me that this phase is slowly disappearing. May our young people be spared from being infatuated with them. Instead we should honour people who conduct themselves in a civilized fashion. We are now working on the best ways to help raise our young people and to re-educate our older people.

Re-educating older people isn’t very easy, but that’s what we face in this life. Many of those who had made careers for themselves during Soviet times are the ones crying now when some Lenin monument is toppled, and there’s not much else one can do with them.

The big task ahead of us now is raising young people the way they need to be raised. It’s a complicated matter, and much remains to be accomplished before our schools and our universities can be said to be attending to this manner of instruction.

The churches have a big role to play as well. I thank God that in our churches and religious organizations there are many nationally conscious people who have an interest in working towards these goals, and they have been working, and preaching, and organizing various charitable groups, resulting in the formation of good citizens. Such people do exist; they just need to be found. We have this monumental task ahead of us, and we are at the threshold of fundamental changes. For now, simply being on this path is very important.

___________________________________________________________________

The complete text of this interview is found in the archives of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory.

“Maidan: An Oral History” is a project of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory and the Foundation to Preserve the Memory of Maidan, with the goal of collecting video and audio testimony from activists of the Euromaidan about the events of the winter of 2013-2014. These recordings will become the basis for archives of the Maidan and will serve as a resource base for historians, documentary makers, sociologists, psychologists, and others. In the future these materials will be accessible to the general public, and will also be utilized for exhibitions by the Museum of Freedom/ Museum of the Maidan.

The first video of the Foundation to Preserve the Memory of Maidan and additional information about it can be found here.