De-humanization first, then their destruction can be justified

Steve Komarnyckyj explains the title of his lecture by saying the following: “Those politicians, and diplomats who know of what happened in 1933, but choose to avert their eyes or keep silent have made a bargain with Satan, selling their souls for their careers. While dancing with Stalin on the graves of the dead they have forgotten their obligations before humanity. The Holodomor was a crime against each one of us. We have to remember the truth together and resolve that such acts will not be allowed to re-occur. There is no other path to a better world.”

In his novel, "Forever Flowing," Vasilii Grossman writes the following: "In order to massacre them, it was necessary to proclaim that kulaks are not human beings. Just as the Germans proclaimed that Jews are not human beings."

Komarnyckyi notes the condescending attitude of Community Party officials during their raids on people’s homes in 1932-33: “‘Why have you not perished’ - and here the activists would use the word zdokh which is used of the death of an animal rather than a human being.” He refers to “Boris Antonenko Davidovich, whose work ‘Death’ is one of the most significant works of the 20th Century,” and that the author “understood how the ideal of equality could be used to seduce people into acts of brutality and ultimately result in the Holodomor and the Gulag.”

"They are kulaks, not human beings" formed part of the lexicon of the dark world that made the famine possible, which Malcolm Muggeridge referred to as a "macabre ballet." Such phrases rival those employed by the statistics bureaus that registered the deaths as death not from famine, but from "digestive ailment", and such language as used by police to describe the personal use of grain as the "theft of socialist property."

Enormous losses, an enormous task of remembrance

Any meditation on the famine begins as a heavy burden because of the sheer magnitude of the losses. This is why Malcolm Muggeridge, who spent eight months in the Soviet Union in 1932-33, felt at a loss for words to describe the famine. Ian Hunter wrote that while Muggeridge looked back on his articles about collectivization in Ukraine as being 'very inadequate,' "it is only because the sheer horror and magnitude defied expression even by so adept a communicator." Muggeridge wrote in “Winter in Moscow” that "Whatever else I may do or think in the future, I must never pretend that I haven’t seen this.”

Miron Dolot, author of "Execution By Hunger," dedicated his memoir about surviving the famine "to those Ukrainian farmers who were deliberately starved to death during the Famine of 1932-33, my only regret being that it is impossible for me to fully describe their sufferings."

Holodomor as Genocide

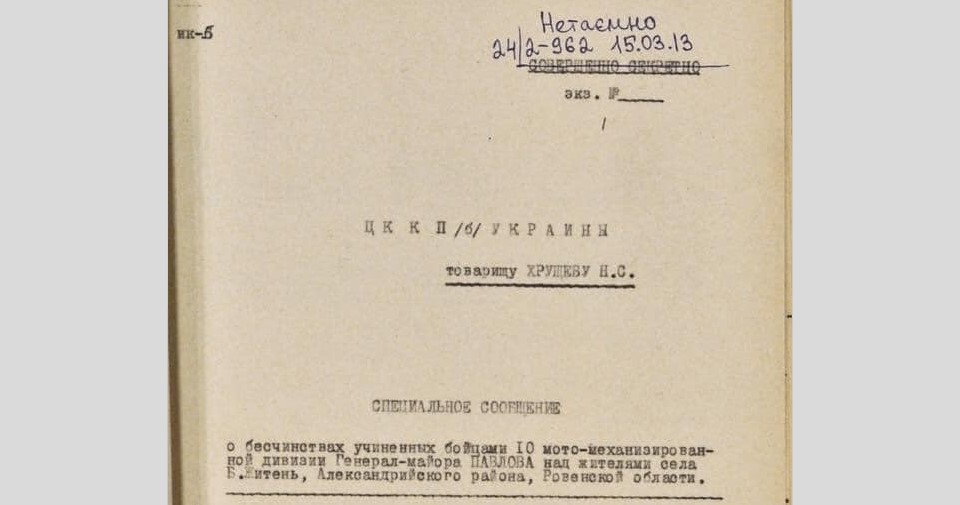

Komarnyckyj makes the argument for the Holodomor as Genocide based “on hundreds of thousands of eyewitness testimonies and the documents showing that massive enforced starvation was inflicted on Ukraine in 1933.” British journalist Gareth Jones wrote that “...there was no bread, many children had swollen stomach, nearly all the horses and cows had died and people themselves were dying.”

For Komarnyckyj, the Holodomor, or Genocide Famine of 1932-33 in Ukraine occurred when “Stalin and his associates planned the mass starvation of Ukrainians and signed the orders and directives.” By 1933 “Stalin had introduced a number of measures which included removing almost everything edible from the rural population and sealing the borders of Ukraine...”

Background to genocide

The Holodomor “is linked to a wave of executions focused explicitly on Ukraine’s political, cultural, and spiritual elites which began in 1930 and has no equivalent in other regions of the Soviet Union,” writes Komarnyckyj.

“The programme that the Russian Communist party adopted in 1919 foresaw the creation of a system of collective agriculture and collective farms.... The Kulak or in Ukrainian, Kurkul, that peasant who had perhaps with their own sweat and enterprise become a little more well off were targeted as the ‘chief and most ardent enemy of collectivisation’ in a plenary resolution of the Ukrainian communist party of December 1930.

“By the end of 1931 the campaign of dekulakisation ceased because most peasants had now joined the collective farm and been stripped of control over the land they lived on and the crops they grew. An ideology that had promised equality had resulted in the enslavement of many of the peasants. During 1931 the chaotic reforms resulted in a paradox that peasants would find themselves surrounded by food but hungry as the dead hand of the state took bread from their mouths.

"On 7th August 1932 the Soviet Union introduced a law to strengthen the defence of Socialist property popularly known as the law of five ears of grain, this allowed peasants to be shot, or if there were extenuating circumstances, jailed for 10 years for taking grain that was state property. This meant that the peasantry could be murdered for trying to eat the crops they had grown.”

The Holodomor as a weapon to destroy Ukrainian Nationalism

In his lecture, “Dancing with Stalin,” Komarnyckyj makes the connection between famine and ending Ukrainian nationalism: “It is true that during 1932 grain was being requisitioned from all across the Soviet Union, a fact which is used by revisionist researchers to call into question the ethnically targeted nature of the Holodomor. However, from August that year onwards Stalin had become increasingly concerned at the possibility of Ukraine separating from the Soviet Union. In a letter of 11th August to Kaganovich he stated that he believed that Ukrainian nationalists working together with Polish spies were preparing to sever Ukraine from the Soviet Union and that the Ukrainian party was becoming a ‘caricature of a parliament’. He stated bluntly that ‘Unless we begin to straighten out the situation in Ukraine, we may lose Ukraine.’"

Further, he writes that “the settlement, from 1933 onwards, of people from other regions of the Soviet Union into areas where much of the Ukrainian population had been exterminated can be linked to statements by communist functionaries expressing a wish to crush Ukrainian national feeling.”

“A communist leader speaking in the Kharkiv region in 1934 said ‘Famine in Ukraine was brought on to decrease the number of Ukrainians, replace the dead with people from other parts of the USSR, and thereby to kill the slightest thought of any Ukrainian independence.’”

He gives an example from Great Britain, where the author of a paper on the famine for the Foreign and Commonwealth Office “was guided by a mind which saw Ukraine which saw Ukraine as simply part of Russia and some British academics share that perception, seeing Ukraine almost as a kind of mad experiment carried out by a deranged professor in front of a sceptical audience.”

The Holodomor as an act of Terrorism

Komarnyckyj describes a phrase used by Yuriy Lavrinenko, referring to the Ukrainian writers in a book he compiled as ‘the executed generation.’ “In an anthology that covered the period 1917-1933, he used the term “’a terrorist blow’ to refer to the genocide famine.” Lavrinenko’s anthology covers the period 1917-1933. “The story of this renaissance is best summarized by (Mykola) Khyylovyj whose slogan ‘Away from Moscow’ would be followed by his suicide in 1937. He took his own life to avoid to executioner’s bullet or a death by exposure and malnutrition in some labor camp.”

While religion in general had been considered as an "opium of the masses" and therefore undesirable as the society evolved in the desirable direction of Communism, it can further be said that the policy of Ukrainian renaissance of the 1920s, Ukrainization, was likewise an opium of the people, one of those "one step backwards in order to make two steps forward" type of concessions that made less and less sense as Stalin consolidated more and more power; neither religion nor Ukrainian nationalism could serve any evolutionary purpose as collectivization progressed into the 1930s.

Neither could the lives of millions of people.