A military of a million people is not just an army – it’s a city on the move. Ukraine’s armed forces have grown to this scale through necessity, but managing such a vast organization has created extraordinary challenges.

The problems include unstructured mobilization, a lack of demobilization policies, the absence of mechanisms to replace incompetent or abusive commanders, insufficient troop rotation, etc. As a result, the same soldiers bear the burden of combat indefinitely, often without any rest or break, leading to increased feelings of unfairness and growing desertion.

Things started to change after President Zelenskyy met with civil society representatives in October 2024. Following discussions with military volunteers Maria Berlinska, Lyuba Shipovich, and others, the military started slowly introducing reforms.

So far, the team of Deputy Defense Minister for Digital Transformations Kateryna Chernohorenko has implemented most of the changes. One significant change allows soldiers to request reassignment to different units within the military—a process that was previously bureaucratically complex and often impossible. Another key reform opened new career paths by allowing combat-experienced civilians to pursue military leadership roles without requiring traditional military academy education.

Yet, more should be done, including establishing fixed terms of service, improving training programs for new recruits, and making it easier to demote and dismiss ineffective commanders.

Ukraine lets soldiers switch units as army reforms begin

Until recently, Ukrainian soldiers faced a tough reality: once assigned to a military unit, they were effectively stuck there. With no way to transfer and no end date to their service, soldiers could only leave their units through injury or death—a situation that took its toll on both morale and military effectiveness.

This inflexibility proved especially problematic when soldiers served under poor leadership. While many Ukrainian commanders have demonstrated excellence, some units suffered under problematic leadership, as illustrated by the recent case of the 211th Pontoon Bridge Brigade. There, the abuse reportedly extended beyond monetary demands, with soldiers forced to contribute labor to the commander’s private residence construction. With no transfer options available, soldiers trapped in these situations had no escape.

The major change happened in November 2024, when the military rolled out a new transfer system. Now, through the Army+ mobile app, soldiers can switch units within just three days. The system’s impact was immediate – over 2,000 approved transfers in its first 18 days and nearly 6,000 in less than two months, showing how badly this change was needed.

Soldiers in frontline units still need their commander’s approval to transfer – a rule that makes sense for maintaining combat readiness but can be problematic when the commander is part of the problem. According to Chernohorenko, this issue will be partially resolved through moderation by the Armed Forces Personnel Center, allowing soldiers to appeal if their transfer requests are rejected.

82% of Ukrainians back mobilization but want reform

Most Ukrainians support mobilization in principle – a solid 82% believe it’s “necessary but must be more fair and reasonable.” A recent survey by Texty found that among men who don’t have exemption documents and aren’t currently serving, about 35% are ready to be mobilized, and 50% would serve if officially summoned. The main drivers are protecting family and country, though surprisingly, some see military service as a meaningful break from civilian routine.

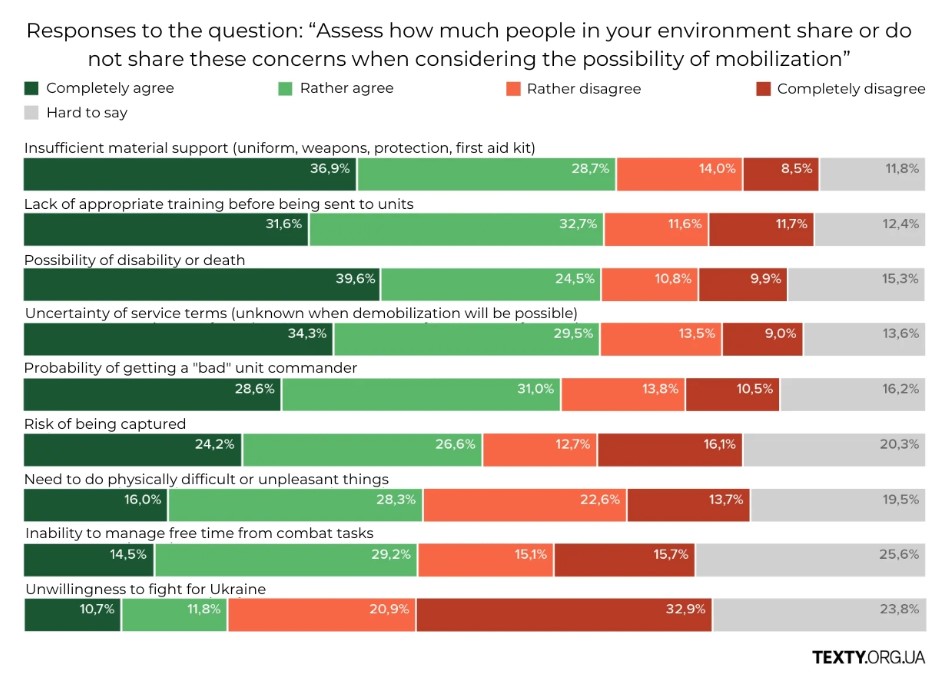

The same survey revealed a telling hierarchy of concerns among potential recruits. While combat risks are an expected deterrent, what’s striking is that respondents ranked serving under poor commanders as a greater worry than the possibility of enemy capture. This fear of bad leadership has emerged as one of the most significant barriers to recruitment, along with equipment shortages, open-ended service terms, and lack of appropriate training.

These fears do not necessarily reflect the objective situation but mostly aren’t unfounded. While the 211th Brigade scandal made headlines, it represents a broader pattern. Across various units, some commanders have been caught demanding personal favors, engaging in verbal abuse, and weaponizing leave permissions and unit transfers as punishment tools.

The culture of false reporting up the chain of command is even more troubling. Serhiy Filimonov, the well-respected Da Vinci Wolves battalion commander, didn’t mince words when discussing recent Russian advances near Pokrovsk in Donetsk Oblast.

“The higher command sets unrealistic tasks for units. Generals who don’t understand their units’ capabilities and aren’t oriented to the actual situation at the line of contact,” he wrote on Telegram.

The core issue isn’t just about having some problematic commanders—you’ll find those in any big organization. The problem is that there’s no good way to spot these issues early and deal with them effectively. The new unit transfer system might help patch some of these holes, but military experts say it’s just a start. What’s needed is a more comprehensive approach to holding everyone—from platoon leaders to generals—accountable for their decisions and actions.

Ukraine breaks military glass ceiling for combat-tested civilians

Until recently, Ukraine’s military advancement system remained anchored in peacetime bureaucracy—promotions were largely based on time served rather than battlefield performance. This created a paradox: experienced civilian recruits who proved themselves in combat hit institutional barriers, while underperforming career officers remained entrenched, merely shuffling between units when problems arose.

A breakthrough came on 2 January 2025 with a transformative Ministry of Defense decree. The new rules allow soldiers and sergeants with civilian leadership experience to advance to officer ranks—up to the colonel level—without traditional military education requirements. The criteria for “management experience” are notably inclusive, requiring only two years of supervisory experience in any civilian role, regardless of team size.

This reform has unlocked advancement opportunities for thousands of capable personnel who were previously confined to sergeant positions despite their proven abilities. Now, these experienced leaders can ascend the chain of command, bringing their battlefield insights and management expertise to higher levels of military leadership.

Keeping soldiers alive should become a key metric

Perhaps most troublingly, there’s no official metric for one of the most crucial aspects of military leadership: keeping soldiers alive. A Texty investigation revealed that officers face no formal consequences for high unit casualty rates. While many commanders do everything possible to protect their troops out of personal conviction, the system relies solely on individual moral compasses.

“A commander’s effectiveness should be measured by concrete results,” argues Maria Berlinska.

She suggested straightforward metrics: casualties and equipment losses versus enemy losses. This is business logic applied to military reality—brigade commanders, like CEOs, manage thousands of people and billions in resources.

Now it appears that Berlinska’s suggestions were taken over by officials.

Chernohorenko outlined that the Ministry of Defense is preparing a new digital system for commanders’ performance monitoring. It will include two key criteria: the number of liquidated enemy military equipment and personnel and the number of Ukrainian losses, thus effectively combining both incentives—to perform the task and keep personnel alive.

Importantly, the loss criteria will include the number of desertions and unit transfer requests, which can lead to the poor evaluation of ineffective commanders. This new system is expected to help military commands make data-based decisions regarding staff promotion, unit enlargement, or possibly disbandment.

If soldiers start leaving a particular unit en masse, that’s a clear red flag about its leadership.

“If everyone is leaving this commander,” Berlinska notes, “that’s probably a signal that the commander needs to go.”

It is too early to evaluate how this new system will work. If it helps demote poor commanders, it would be a major structural success.

“If you fail your tasks, you go down, even to a platoon commander or regular infantry soldier,” Berlinska emphasizes her vision.

100,000+ desertions signal the cost of delayed military reform

Flawed military rules concerning the unconditional authority of commanders and the absence of a defined service term discouraged potential recruits from mobilization and prompted service members to go AWOL (absent without leave).

Numbers reveal that between January and October 2024, prosecutors opened 88,000 cases for soldiers leaving their units—59,000 for unauthorized absence and 29,000 for desertion. That’s nearly double what they saw in 2022 and 2023 combined, while the total figure for all three years of war is significantly over 100,000.

Most notably was the case of the 155th Mechanized Brigade, which saw approximately 1,700 soldiers going AWOL throughout 2024, per Ukrainian military journalist Yuriy Butusov. The brigade’s challenges, including poor leadership and inadequate training, underscore the systemic issues that drive such alarming desertion rates.

This demonstrates how badly delayed were the military reforms, but hopefully, it is not too late.

Acknowledging its own failures, the Ministry of Defense issued a decree on 29 November 2024 granting amnesty to soldiers who had gone AWOL, provided they returned to service by 1 January 2025. Over 9,000 military personnel returned to the army during this period, choosing new units to serve. The government subsequently extended the amnesty ruling to March while working on demobilization legislation and other reforms.

Critical mobilization issues remain unresolved

While many changes have already been introduced, the government largely ignores the elephant in the room – mobilization.

But military experts speak about its problems straightforwardly. A former assistant to Ukraine’s Commander-in-Chief and coordinator of the Ukraine-NATO platform describes the current open-ended mobilization as “a one-way ticket.”

“With no clear end date, joining the army means giving up hopes for a normal life, leaving your profession behind, possibly forever,” he explains.

Berlinska highlights the unanswered society’s demand for justice:

“I would fulfill society’s and army’s demand for fairness. People need rest,” she emphasizes. “The same people have been burdened with war this whole time.”

She advocates replacing the current one-month-per-year leave policy with several weeks off every 3-4 months. This solution would require more troops to enable regular rotations, but it could help prevent future crises.

The growing divide between frontline soldiers and civilian life has contributed to rising AWOL rates. While the recent tripling of wartime military tax for most of the population marks a small step toward greater equity, deeper inequalities persist.

Over one million government officials and “critical infrastructure” employees remain exempt from mobilization, along with millions of others who qualify for exemptions under peacetime rules—including those with three or more children, disabled dependents, or student status regardless of age. This legislation, designed for peacetime conscription service, proves deeply inadequate for wartime demands.

Meaningful reform—including reduced disparities between frontline and rear conditions, fixed service terms, and regular rotations—depends on expanded mobilization, which in turn requires legislative changes. Yet no leader, whether in government, parliament, or the Zelenskyy administration, has shown a willingness to champion these necessary but politically costly reforms.

Training and equipment: other gaps that demand attention

In the above poll, Ukrainians indicated equipment shortages as the most urgent threat to morale and combat effectiveness. This popular opinion neglects the fact that the current situation with equipment is the best during the entire time of war due to increased domestic production and international supplies. Still, it’s not groundless. Over 30 territorial defense brigades operate with just small arms and mortars despite their potential to become fully mechanized units. They lack essential equipment – armored vehicles, artillery, and electronic warfare systems – delayed in Western deliveries, states Oleksandr Danyliuk, former advisor to the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

Training is the key to scaling up the positive experience and effective skills. Journalist Valeriya Parvlenko highlights cases when soldiers receive mostly theoretical instruction rather than the hands-on practice needed to build combat-ready skills. The military also lacks an effective system for sharing battlefield experience between units – a gap that history shows can be devastating. During World War II, the US military’s decision to turn its best pilots into trainers created a constant stream of skilled aviators. At the same time, Japan’s failure to do the same left them with plenty of aircraft but too few qualified pilots by 1943.

Command structure issues also demand attention. Respected military commanders argue that Ukraine must abandon its current practice of deploying small company or battalion-sized units to reinforce troubled areas. This strategy creates command and control chaos.“We need a divisional system. This will change management,” says Chief of Staff of Azov Brigade Bohdan Krotevych, highlighting the need to enlarge effective units and centralize command.

While Ukraine has demonstrated its ability to implement reforms even during active combat, as shown by the new unit transfer system, addressing these fundamental gaps—particularly in mobilization rules—remains crucial for success in a prolonged war of attrition.

Read more: