Kateryzhina Prokhazkova, an expert at the Prague-based Sinopsis analytical center examines how Russia infiltrated and transferred malicious and false news over the course of several years into Chinese state discourse.

Russian disinformation narratives about “Ukrainian Nazism” and foreign influence are widely disseminated in China’s state-run media and through state-sponsored social media networks that target China itself, Taiwan and the Chinese-speaking diaspora.

This is facilitated by the close ties and official agreements between the Chinese and Russian media, as well as Beijing’s strict control over the Internet and social media.

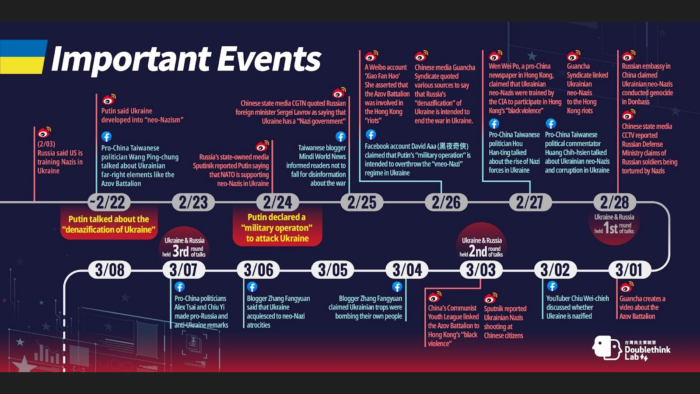

Doublethink Lab (DTL) is a Taiwan-based civil society organization devoted to researching malign Chinese influence and information operations, as well as disinformation campaigns. Analysts at Doublethink Lab, who monitored Chinese state and social media from mid-February to the end of March, found that Chinese sources were using and spreading Russian disinformation narratives about Ukraine, such as the oft-repeated discourse that “neo-Nazis” were operating in Ukraine, and that the Russian military was carrying out a special “denazification” operation.

In addition, Chinese media and bloggers share disinformation that links Russia’s discourse about Ukrainian “Nazism” to the protests in Hong Kong. In this way, they manipulate Chinese readers by building a negative image of Ukraine.

The Russo-Ukrainian war and Ukraine’s aspiration to live in a democratic society, they say, were caused by “foreign forces interfering directly in the internal affairs” of another state and by “foreign-funded Nazis.”

The words “foreign intervention” is a standard argument used by Chinese politicians when responding to any criticism that draws attention to the human rights situation in the PRC, the Uighur genocide in Xinjiang, or the violence in Tibet and Hong Kong. In addition, such fake news casts doubt on international defense alliances (such as NATO), which the Russians and Chinese see as a global threat, and fuels anti-Western and anti-American sentiment among the Chinese.

Spreading Russian disinformation narratives about Ukraine across Chinese information space

The Russo-Ukrainian war has put China in the difficult position of choosing between supporting its main ally, Russia, and avoiding sanctions other countries may impose if it provides military aid to Moscow or tries to help Russia circumvent sanctions.

On 1 April, the European Union and China held a joint summit via video conference, where the European leaders reminded Beijing that restoring peace and stability in Ukraine is a shared responsibility.

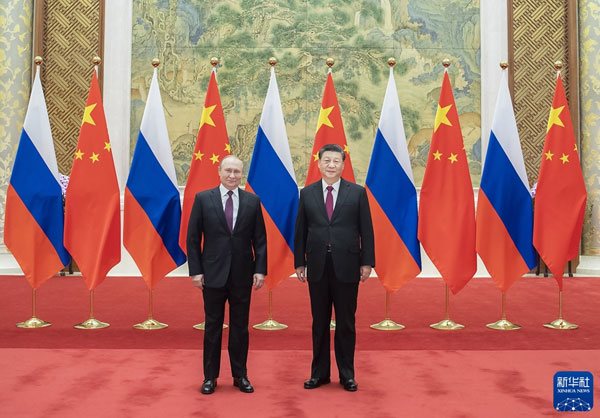

Just a few weeks before the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, General Secretary Xi Jinping and Russian President Putin signed the so-called Olympic Declaration, which unequivocally confirmed that the two powers would support each other and stand together in all spheres of activity.

China and Russia are committed to “deepening back-to-back strategic cooperation” Xi was quoted as telling Putin.

“This is a strategic decision that has far-reaching influence on China, Russia and the world,” Xi added, according to the official Xinhua News Agency.

Faced with “a complex and evolving international situation,” China and Russia chose to create a negative media image of the war in Ukraine, spread and amplify it to their respective domestic audiences. Thus, from the beginning, China’s official media did not call the Russian invasion an invasion per se but described it as a conflict provoked and managed by the US and NATO.

“The parties oppose the further expansion of NATO, and call on the North Atlantic Alliance to abandon the ideological approaches of the Cold War,” the joint statement said.

Sino-Russian cooperation on the media front

According to the Doublethink Lab report, cooperation between Chinese and Russian state media has intensified and even has an official basis.

In 2015, Russia Today (RT) TV channel signed a cooperation agreement with China Central Television. Since 2018, China Central Radio and Television has been working with the state-linked newspaper Rossiyskaya Gazeta on the joint production of Sino-Russian subtitles and headings.

In addition, Russian official media, including the Sputnik news agency, publish information and news in Chinese to Chinese readers and operate accounts on the popular Chinese social network Weibo.

Thus, all media outlets in the PRC are ordered to publish only official news issued by the state-run newspaper People’s Daily, the Xinhua news agency or China Central radio and Television, i.e. media that signed the above-mentioned content-exchange agreements with their Russian counterparts.

From English into Russian into Czech: re-translation as a Russian propaganda’s manipulation tool

Russian propaganda is also shared by government accounts on different social networks, Twitter, and Facebook. The latter are blocked in China, but this does not prevent Chinese propagandists from using them to influence Chinese-speaking audiences in other countries.

They also refer to Russian social media accounts as a source of information and further modify Russian propaganda news to suit their needs.

Jerry Yu, author of the Doublethink Lab report, explains it this way: “The tendency is clear: one side creates and the other expands, distorting information in a way that benefits both countries.

As a result, the Chinese public supports Russia’s invasion of Ukraine despite the official “neutral”" position of the Chinese government.

Russian disinformation narratives about the “nazification” of Ukraine in Chinese information space

Other articles promoted bogus public opinion polls claiming that only a small percentage of Ukrainians support their country joining NATO.

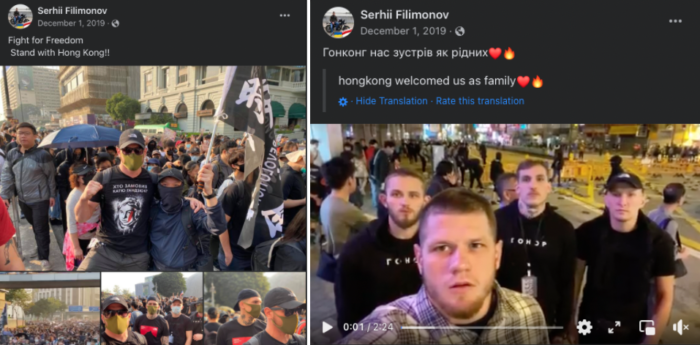

Three days after the start of the full-scale invasion, reports from 2019 appeared on China’s Weibo network and state-linked blogs, sharing a photo of Ukrainian veterans seen at pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong. They claimed that the US was financing the participation of members of the Azov Battalion in various gatherings and thus sowing discord and confusion around the globe.

This is not the first time that Russian and Chinese state media have reinforced and amplified each other’s anti-American narratives. In another example, Russia’s state-run TV station RT in January 2020 broadcast a documentary called ‘Hong Kong Unmasked’, accusing the CIA, Freedom House, and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) of playing a behind-the-scenes role in the Hong Kong protests.

At the beginning of March 2022, pro-Beijing social networks were flooded with Russian fakes about Ukrainian "neo-Nazis" shooting Chinese citizens and torturing Russian soldiers.

Russian disinformation narratives targeting Taiwan and the Chinese-speaking diaspora

In the following days and weeks, disinformation campaigns about “Ukrainian Nazism” proliferated in Taiwanese media.

On 27 February, Taiwanese pro-China politician Hou Han-Ting (on YouTube) and pro-China media commentator Huang Chih-Hsien (on Facebook) published false information regarding the rise of “neo-Nazism” and related corruption in Ukraine. This information appeared around the same time as the emergence of similar material on China's Weibo (see timeline below).

Content accusing Ukraine of “neo-Nazism” and reporting links between the Azov Battalion and the Hong Kong movement is distributed across various Chinese social media, including video-based platforms such as Douyin, Xigua and YouTube. This content is widely accessed by Taiwan and the Chinese language diaspora outside of China.

“Nazis” wherever you look!

Not only does China spread disinformation about the Russo-Ukrainian war, but it also imposes censorship on all independent reporting on the situation in Ukraine - for example, Chinese citizen journalist Wang Jixian, who reported on the invasion directly from central Odesa, or the open letter by top Chinese professors calling on Russia to end the war in Ukraine.

In this regard, the development of events around the initially strictly censored word “Nazism” is interesting. According to Charlie Smith, co-founder of Greatfire.org, a censorship monitoring site, content with this word has long been blocked by most Chinese Internet companies.

But, during the first month of the war, this keyword was removed from China’s censorship lists in order to follow up on Russian disinformation narratives - which trumpeted far and wide that Moscow had launched a “special operation’ in Ukraine and charged the Russian military to overcome “Nazism and fascism” in the country.

[bctt tweet="Sometimes what is not being censored can be more telling than what is being censored. How Russian propaganda narratives flourish in Chinese information space" username="Euromaidanpress"]

These words became the most important justification for the invasion in February 2022.

“Usually once a word ends up on that [censorship] list, it very rarely comes off. Sometimes what is not being censored can be more telling than what is being censored.” says Charlie Smith.

Chinese vs American narratives

David Bandurski, analyst and director of the China Media Project, told The Guardian that China’s state media began amplifying and spreading Russian narratives way back in 2021, portraying Russia’s military actions as primarily defensive against NATO's increased presence in Moscow’s spheres of interest.

In response to questions from Western journalists, Chinese authorities denied spreading disinformation campaigns. In his press conference on 25 April, 2022, spokesperson of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Wang Wenbin claimed that “facts have proven that the US is the biggest spreader of disinformation, culprit of coercive diplomacy and saboteur of world peace and stability.”

Nevertheless, the media department of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs continues to spread conspiracy theories about US-funded bioweapon labs in Ukraine. It has also amplified conspiracy theories about Hunter Biden, George Soros, the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and Covid-19.

“The point here is to undermine US credibility over the longer term, and to push for a remaking of the international system. In this endeavour, Russia has been China’s most intimate partner,” underlines Bandurski.

Currently, Western sanctions have begun limiting the spread of Russian disinformation narratives and have started to positively impact media and internet platforms, including in the EU.

Nevertheless, the collaboration between Russia and China, and the impact of Russian propaganda channels on the global Chinese-speaking diaspora, should not be underestimated. Chinese disinformation campaigns continue to spread Russian propaganda through Weibo, Douyin, YouTube, and other platforms, creating a negative image of Ukraine among Chinese-speaking users.

Read more:

- A guide to Russian propaganda

- Strengthening the security resilience of Ukraine: military, energy, cyber

- What Ukraine’s civil society wants to tell at Biden’s Global Democracy Summit

- Here is how the US can truly help Ukraine move forward

- Ukraine’s Prime Minister sees civil society as a key reform partner

- Is Ukraine getting closer to NATO membership?

- Russian disinformation activities accompanying the MH17 trial

- The secret labs conspiracy: Russian propaganda’s converging narrative

- Ten embarrassing moments in Russian disinformation of 2019

- Pro-Russian disinformation operations in Kherson: a new-old challenge for Ukraine’s national security

- From English into Russian into Czech: re-translation as a Russian propaganda’s manipulation tool