The scope of EU dependence on Moscow also reveals that Moscow will collapse should the EU disconnect from Russian oil and gas

According to the CREA calculator, since the beginning of Russia's invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, the EU paid over EUR36 billion to Russia for fossil fuels, as confirmed by EU officials. In comparison, the military aid that the EU as an organization has provided to Ukraine is more than 20 times smaller - EUR1.5 billion. In addition, France separately provided EUR 200 million and Germany -- about EUR 100 million as military aid, while the total military assistance from the US, Ukraine’s biggest donor, amounted to $2.5 billion as of 14 April 2022.

Between 14 March and 10 April 2022, using only tankers through the Bosporus and Dardanelles, Russia exported 10,040,000 tons of oil worth $6,7 billion. More than half of this oil was exported to the EU countries, with Türkiye and Egypt also receiving a significant share, according to the data by the Black Sea Monitoring group.

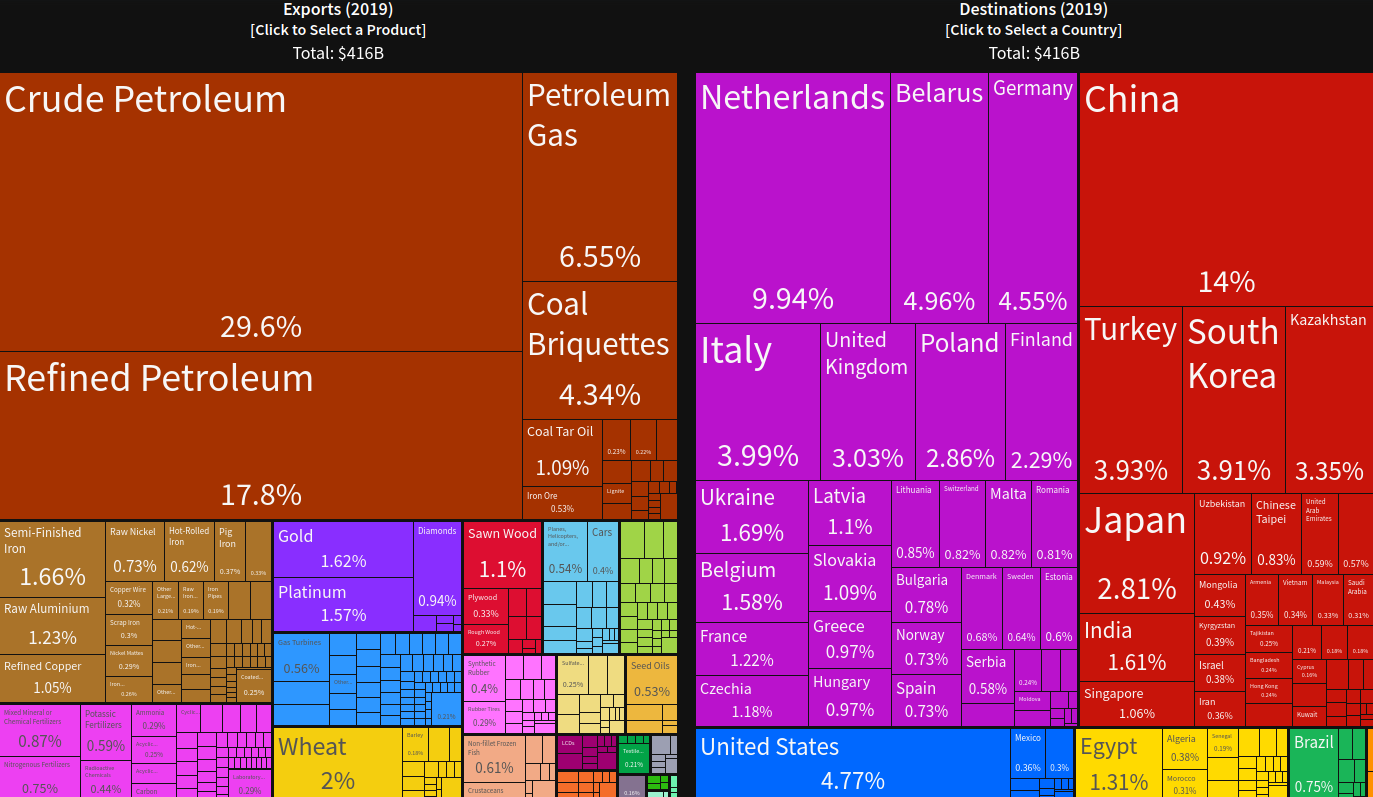

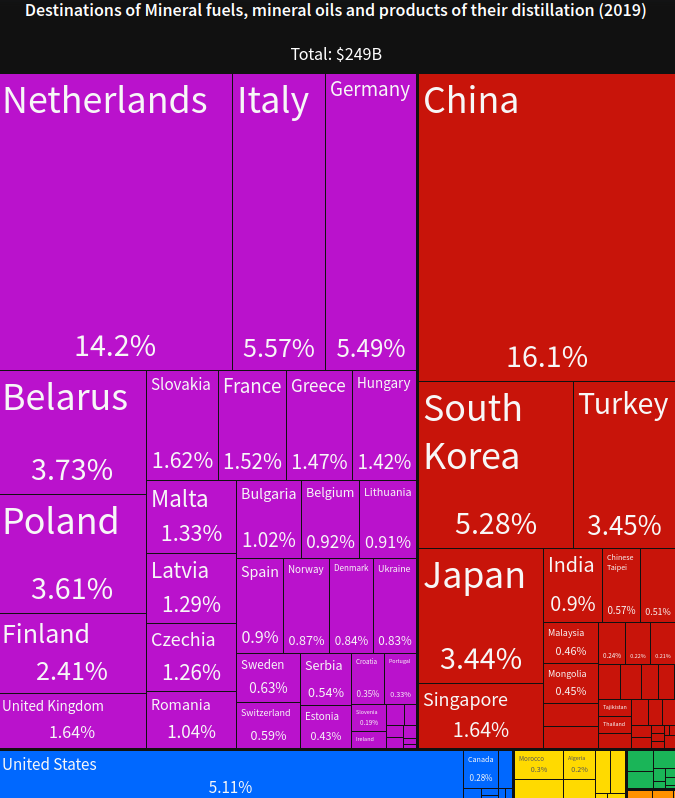

Calling Russia a gas station country is not an exaggeration. 50 to 60% of Russian annual exports are oil, gas, coal, and other mineral fuels, according to the oec.world database. More than 50% of Russian fuel exports, as well as exports in general, were purchased by the EU companies.

According to forecasts, Russian energy exports could hit a record $320 billion in 2022 if the EU doesn’t abandon Russian oil and gas. So far Russia is meeting this target. The adopted EU embargo on Russian coal, which comes into effect in August, will decrease Russian energy exports by only 1-2%.

How did the EU become a hostage to Russian oil and gas?

This was able to happen because the EU neglected its own norms of diversification. Why the European Commission granted Russia much more than its fair share of the market remains open for investigation. But this was definitely one of the factors of additional Russian revenue that enabled it to finance the war against Ukraine in 2022. The danger of this dependency has already been examined in our previous article:

Now experts share some additional details that demonstrate that Kremlin lobbyists in the EU were working strategically for years to achieve the current state of affairs, while the EU stood blind.

Serhiy Kuyun, a prominent Ukrainian energy expert on the inside design of the Russian oil industry, said to Euromaidan Press that as early as 2003 Russia started its systematic efforts to take full control over the European energy market.

“In 2003, Ukraine finished the Odesa-Brody oil pipeline from the Black Sea port to western Ukraine, to supply non-Russian oil to Ukraine and Europe. But the Russian lobby managed to block this pipeline as a supplier of alternative oil to the EU and instead contracted it to use to supply Russian oil to Odesa. Later, Ukraine tested the transfer of Azerbaijani oil to Europe by a parallel pipeline. But this pipeline was blocked by Hungary. For the first time, it became known that entire factions of the Hungarian government were directly lobbying Russian interests. Today Hungary has banned the supply of not only weapons but also oil to Ukraine. No other country has imposed such bans.”

Kuyun adds that since Ukrainian seaports are currently blocked, oil and fuel imports to Ukraine are being rearranged from the western border via rail. Given that the European rail network is not prepared for such volumes, this is problematic and expensive. At the same time, the Hungarian-Ukrainian petroleum pipeline that could help now is blocked by Hungary and can’t be used. 60% of oil refined in Hungary is Russian. This directly violates European directives, according to which the country should not have more than 30% of energy supplies from one source.

How does the Russian gas lobby work?

Kuyun names two factors. First, European officials are employed by the Russian company Gazprom among other ways to financially stimulate European officials to buy Russian energy and build informal connections inside governments. Then, in instances when this scheme doesn’t work, Moscow uses direct blackmail. He gives examples:

- 2006. Lithuania refused to sell its only refinery to Russia. A few weeks later, Russia cut off oil supplies to the refinery. It was then said that the pipeline broke down and needed to be repaired. 15 years later the repairs are still not completed

- 2022. In March, the oil shipment terminal in Novorossiysk suddenly broke down. Exports of 80% of Kazakhstan's oil were blocked. Nearby, the terminal that shipped Russian oil, also in Novorossiysk, continued to operate. It is unknown how long the "repair" will take. Kazakh exporters are wondering how it could have broken if it had recently been repaired.

- And the last example is the artificial increase of prices in Europe to $2,000 per 1,000 cubic meters of gas from Russia as pressure to launch Nord Stream Two certification. This is the culmination of Russia's policy of destroying alternative gas supply routes to Europe.

"Now Germany wants to build LNG terminals. Imagine if they were already built in 2014 after Russia occupied Ukraine's Crimea and Donbas. The EU would be able to abandon Russian oil and gas easily and quickly," Kuyun notes.

Poland is a positive example of diversifying its energy imports. In 2020, Russian oil accounted for 70% of Polish refining. Today it is 30%, and by the end of the year this supply will stop, the Polish government has announced.

Unlike European politicians, Russia has been preparing for this “key moment” for decades. It had worked to build infrastructure that was not economically profitable but allowed Russia to control transfer routes and conduct blackmail, so that it would be hard for the EU to abandon purchases of Russian oil quickly. It used “sweet prices” for market expansion, financial support for political parties and individual officials in the EU, and developing a strong propaganda presence in the European media, Kuyun says.

How can the EU abandon Russian oil and gas quickly?

Specific intermediate measures should be imposed by the EU, while a full embargo, realistically, can be imposed by the end of the year:

"There are worries that the battle for the embargo may last for a length of time Ukraine does not have. It is necessary to demand from Europe intermediate measures that will limit Russian oil exports now. High tariffs, strict rather than recommended quotas, gradual infrastructural blocking of flows… This should speed up the search for alternative sources with the appropriate development of infrastructure projects and trade routes and the emergence of new concrete examples of diversification," Olena Pavlenko, director of the Dixi group think tank and expert in the energy sector, noted.

Olena Pavlenko admitted that the EU may be not ready for a full embargo right now. However, what it should do to stop Russia is to determine a specific deadline for the purchases of Russian oil and gas in Europe and set a specific timeframe for diversification. This will have an immediate impact on Russia:

“The European Union must set a clear deadline. If the EU said that we would stop buying gas in a year or by June of next year, it would bring down Russian stocks and force European companies to look for an alternative. Now there is no deadline and European companies are trying to put pressure on their governments and delay this decision as far as possible. If it was announced that there is no way back and there is a clear deadline, companies would start looking for alternatives.”

These steady measures toward a full embargo have one more advantage over an immediate embargo because they will not lead to a significant increase in price before the EU has alternatives available. There will not be a situation when Russia sells less oil and gas but earns more money:

“There are many countries, including OPEC countries, that can quickly increase production and simply push Russia out of its niche. However, OPEC can use the situation to manipulate prices. To prevent this, the EU and the US have already begun to release oil from reserves. With gas it is more difficult. The Russians have created a situation so that when Europe buys less gas from Russia, there is a shortage in the market, the price rises and, accordingly, the Russians can sell less but earn more. It turns out that they win anyway. With LNG, which is the main alternative to Russian gas, you can only increase deliveries after you have built new terminals, which takes money and time. Up to one year if there is a great desire.”

First steps in the EU

Baltic states have already abandoned Russian oil and gas and Poland plans to do so by the end of the year. Other EU countries mostly make some efforts, albeit on different scales, to limit purchases from Russia.

“Two-thirds of Russia's exports are done by long-term contracts and one-third by short-term ones. This last third is something that can be given up quickly. European companies already do not want to buy this part of Russian oil and it is cheap," Kuyun says. "Contracts are concluded for one year. And there are big penalties. That’s probably why EU countries mostly say that by the end of the year they will stop buying Russian oil.”

In Germany, Russian Gazprom is surrendering its share in some companies, and Germany is looking for other businesses that will take over these shares, Pavlenko adds. But again, she emphasizes, the key thing is setting a deadline for Russian energy. The absence of a specific deadline creates a feeling of ambiguity in which some companies still hope the situation will stabilize and return to previous conditions of Russian dominance. She concludes:

“Germany is the largest consumer of Russian gas in Europe, and everyone will look at what Germany does. Other countries will wait until Germany decides to give up Russian gas. In particular Bulgaria, Hungary and Austria, which are also dependent on Russian gas. Several key countries have to declare a deadline.”

Reportedly, European officials have been drafting plans for an embargo on Russian oil products to be included in the next package of sanctions. However, no official statements were made about this.

Read also:

- US slaps embargo on Russian oil and gas. Will Europe follow suit?

- 10 steps to knock down Russia in the energy sector

- Is freedom from the Russian gas needle possible for EU & Ukraine?

- As Russia’s war against Ukraine escalates, the threat of hunger looms over the world

- “Let’s tell our daughters we love them if we’re about to die in the fire.” How Russian shell hit my home

- “Mariupol people melt snow, drink water from heating mains”: besieged city faces total destruction

- Russia turned Bucha into one big torture chamber. Dispatch from Ukraine

- “Russians are wrecking everything out of envy”: Ukrainian recalls harrowing escape, shares thoughts about Russia