“Ukrainian activists started the protests in Khabarovsk, calling for the disintegration of the federal land,” said Russian propagandist Volodymyr Solovyov, attempting to discredit the ongoing protests in Khabarovsk where protests in support of Sergei Furgalo, the federal land governor dismissed by Putin, are ongoing since 11 July.

“Activists found a Ukrainian ‘national code’ in Khabarovsk. They promote the idea of Khabarovsk belonging to Ukraine. They demand to conduct a referendum and separate the region from Russia. They distribute a Ukrainian map where the territory of Khabarovsk is marked as the [Ukrainian] Zelenyi Klyn,” continues Solovyov, who is a member of Putin’s party United Russia and a popular TV narrator.

Although a clear exaggeration, Solovyov’s statements are not entirely without historical ground.

In the early 20th century, the current Khabarovsk and Primorsk regions on the Russian Far East were called Zelenyi Klyn ("Green Wedge" in Ukrainian) and were populated mostly by Ukrainians. They emigrated there due to the policy of colonization of the Far East promoted by the Russian Empire and continuous repression in European Ukraine.

If the Ukrainian state had succeeded then, the Khabarovsk region could indeed have had a chance to become a Ukrainian colony, being nearly equal in size to European Ukraine.

However, in 1922 the Bolsheviks took control over Zelenyi Klyn. Ukrainians in the Far East faced harsh repression as anywhere else in the USSR. A gradual Russification of the Khabarovsk region and further immigration of Russians to the region led to the assimilation of Ukrainians.

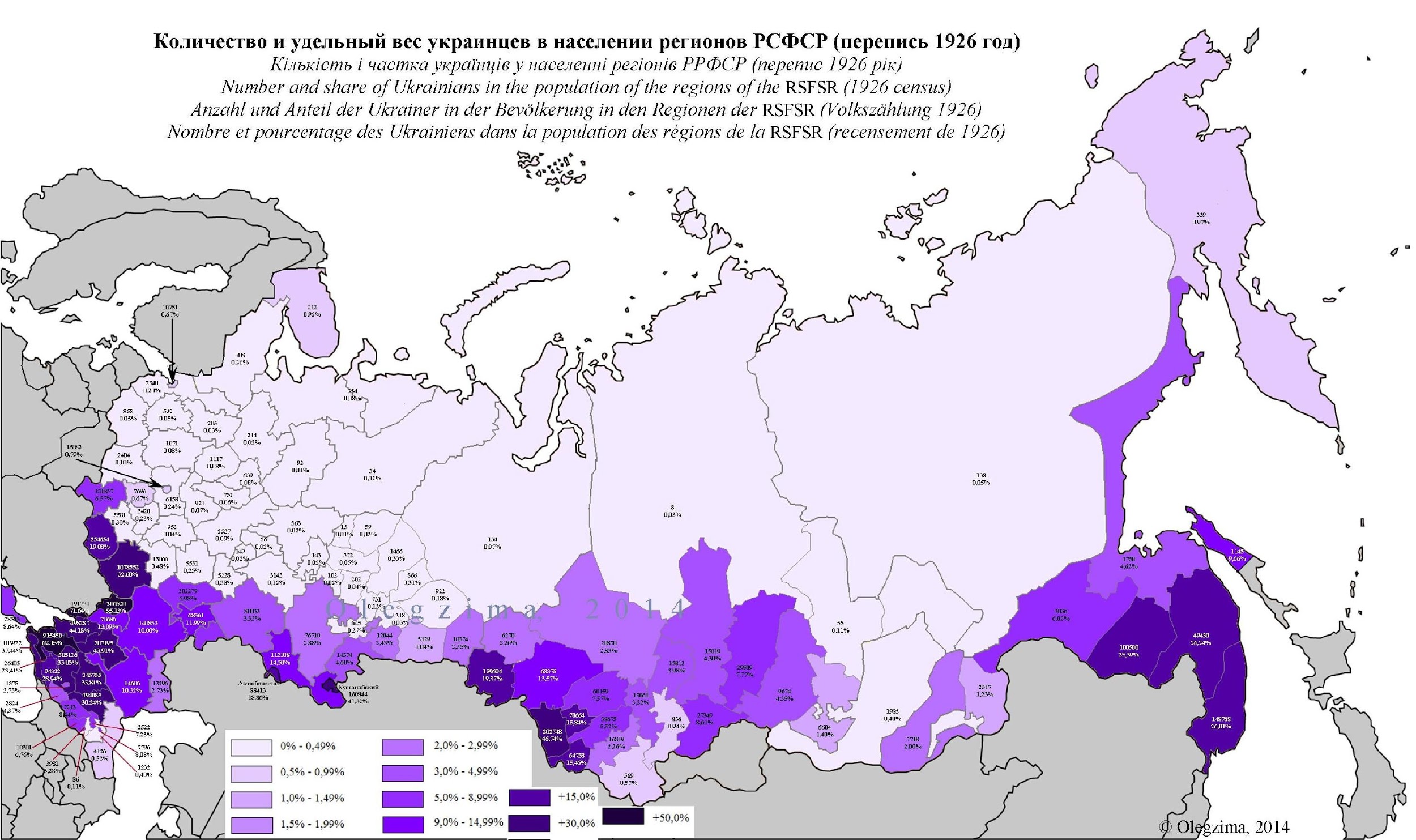

According to the official Russian census, today only 3% of residents of Khabarovsk and Primorsk regions (former Zelenyi Klyn) call themselves Ukrainians, and are the largest national minority in the region.

Due to large-scale immigration of Russians to the region, any claims for regional autonomy based on Ukrainian identity are groundless today.

Nonetheless, the historical period from the 1890s through to the 1920s, when Ukrainians constituted the majority of colonizers moving to Zelenyi Klyn and struggled for local autonomy, are worth knowing about and remembering.

Many of the contemporary protesters in Khabarovsk are descendants of those Ukrainian colonizers who identify themselves as Russians today.

Why Ukrainians colonized the Russian Far East in the 19th century

The first complete census in the Russian Empire conducted in 1897 reveals that the empire was doomed to suffer internal hostility between Russians and Ukrainians.

Overall, 44.3% spoke Russian, 17.8% Ukrainian, 6.3% Polish, and 4.7% Belarusian. Thus Ukrainians were the second-largest ethnic group after Russians and controlled the most valuable lands of the western Russian empire from an economical and geopolitical standpoint.

The general demographic policy of the Russian Empire and Soviet Union was to mix the population of various regions and in that way assimilate all minorities to the only “Great Russian” culture.

This is why south-eastern Ukraine is still populated by a large Russian minority while the Khabarovsk region for a long time was characterized by Ukrainian culture.

[highlight] The city of Khabarovsk was founded in 1858 by an ethnic Ukrainian[/highlight] - a soldier of the Russian Empire Yakiv Diachenko. He also founded 30 other villages and towns in the Far East.

In 2008, on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the city, grateful citizens of Khabarovsk unveiled a monument to him. Full-size and in bronze, the monument was set in the center of the city, on a street named after Taras Shevchenko, the famous Ukrainian poet.

To speed up the process of resettlement of Ukrainians from European Ukraine, volunteers were provided larger plots of land than they had had in Ukraine. This was supported by constant propaganda about the wealth of the Far East. The first relatively large number of Ukrainian settlers came to the Far East in 1860—1861.

A sharp increase in resettlement took place after the initiative of General Pavel Unterberger. In 1882, he organized free transportation of settlers, who were almost exclusively Ukrainian peasants, by sea from Odesa and assigned them the best land in the Far East.

Since the 1890s the new railroad link between Ukraine and the Far East facilitated a further increase in the number of emigrants. [highlight]In total, between 1850 and 1916, 276,300 people officially moved from Ukraine to the Far East. That is 56.54% of all colonizers at the time. [/highlight]

Ukrainians were not the only large ethnic group in the Far East but controlled most of the land and created Ukrainian enclaves

Yet, it would be an exaggeration to say that Zelenyi Klyn became exclusively Ukrainian, as censuses in 1897 and 1926 show.

For example, in the current Primorsk region in 1897, Ukrainians constituted 25% of the population, second to the Russians (34%, table below). Other major groups were Koreans and Chinese.

The 1926 census also shows Ukrainians constituting 25-26% in all regions of Zelenyi Klyn. These censuses, however, were typically distorted in favor of a larger Russian presence, for self-identification as Russian could offer more opportunities and prestige in the Russian empire.

| Russians | 41929 | 33.6% |

| Ukrainians | 31413 | 25.2% |

| Koreans | 22380 | 17.9% |

| Chinese | 21328 | 17.1% |

Altogether, the reality was that the region as a Russian colony formerly controlled by Asians had a very motley ethnic composition. Near the border, mostly Chinese and Koreans lived. In cities, Russians held the majority, prevailing functions of administration. Ukrainians populated the majority of agricultural lands. They used to settle in small village groups, almost exclusively controlling their surroundings and creating huge "islands" of Ukraine in the Far East, as asserted by descriptions of that time.

For example, here is how one of the correspondents of that time, V. Illich-Svitych, described the town of Ussuriysk in 1905:

This is a large Ukrainian village. The main and oldest street is Mykolska [named after St. Nicholas, whose name in Ukrainian is Mykola]. White houses stretch on both sides of the street, still covered with straw in places. At the end of the town... as is often in Ukraine, a pond was set up, near which a mill was built, so that a picture would emerge… like in a popular Ukrainian song… And indeed, among Poltava, Chernihiv, Kyiv, Volyn and other Ukrainian migrants, the people from Great Russian provinces are completely lost, as if infused into the main element of Ukrainians. The market on a trading day, for example in Mykolsk-Ussuriyskyi, is very reminiscent of a town in Ukraine… the same Ukrainian clothes on people. Everywhere you can hear a cheerful and lively Ukrainian speech...

In general, Zelenyi Klyn was the second most Ukrainian region of Imperial and then Soviet Russia after the Kuban to the east of the Sea of Azov near the Ukrainian border, where Ukrainians constituted up to 70%.

Together with Russians, Ukrainians also colonized large areas of agricultural land in southern Russia. As shown in the graph below, according to the census of 1926 Ukrainians were the largest national minority in Russia; they constituted an internal opposition which was disturbing for Russians, along with Ukrainian opposition to “Great Russian unity” in Ukraine proper.

Struggle for Ukrainian autonomy in Zelenyi Klyn

Preserving their Ukrainian lifestyle, colonizers of the Far East created their own Ukrainian schools, business cooperatives, Ukrainian newspapers, and libraries.

However, with the beginning of the First World War, strict measures were introduced and any cultural autonomy declined. Only after 1917, with the beginning of civil war in the Russian Empire, the general chaos allowed a new wave of Ukrainian self-organization.

On 13-14 June 1917, various Ukrainian communities in Zelenyi Klyn of differing political views gathered in Mykolsk-Ussuriyskyi for the First General All-Ukrainian Congress of activists and citizens from the Far East. The Congress allowed further systematic work to achieve Ukrainian autonomy for Zelenyi Klyn.

This was reflected in the decisions of the Second All-Ukrainian Congress of the Far East, held in Khabarovsk in January 1918. It adopted an appeal to the government of the Ukrainian People's Republic to demand from the Russian authorities recognition of Zelenyi Klyn as part of the Ukrainian state.

Delegates also declared that Zelenyi Klyn should become a Ukrainian colony.

Unfortunately, the Ukrainian People’s Republic was led not by a military elite but by historian M. Hrushevskyi and poet V. Vynnychenko, who failed to create a strong Ukrainian army despite means and personnel being available. Therefore the Ukrainian state entered a three-year-long period of war for independence and changes of government.

However, this did not mean they were passive.

In Khabarovsk, for example, an active Ukrainian community was created in 1917. It formed a new Ukrainian school and library, and in the summer of 1917 the first Ukrainian military units in Zelenyi Klyn. They were created by the method of Ukrainization of former units of the Imperial army.

Ukrainian military units were also created in other cities, in particular in Vladivostok. Controlled by Japanese ships during the war, Vladivostok became a hotbed for the Ukrainian movement.

At the Third All-Ukrainian Congress of the Far East, which took place in April 1918, participants decided to struggle for the creation of an independent Ukrainian state of the Pacific and the formation of the Ukrainian Army of Zelenyi Klyn. The leadership was handed over to the National Secretariat (Government) headed by Yuriy Hlushko-Mova.

Between 1917 and 1920, Bolshevik and Kolchak armies competed for control over the Far East. They tried to use Ukrainians in their struggle.

It was common that Ukrainians would support the Ukrainian state and Bolsheviks at the same time or fight in the army of Dmytro Horvat, general of the Russian Empire, and declare their support for the Ukrainian state.

Horvat himself was loyal to Ukrainian autonomy and allowed the creation of Ukrainian troops within his army. The only mainstream line in this mosaic of the 1917-1920 was that Ukrainians of Zelenyi Klyn waited for the political support from the Ukrainian state in Europe that never came.

Until 1922, the Bolsheviks couldn’t entirely establish their power over the Far East. Locals, including Ukrainian emigrants, had their own view of socialism that also included ethnic and cultural rights and elections on the basis of ethnically defined districts – something not in the interest of communists.

Only on 5 November 1922, when the Bolsheviks captured Vladivostok from the Japanese, was the active Ukrainian movement in the Far East brought to an end.

After the wave of Repressions in the 1920s, Ukrainians of the Far East experienced a relative cultural revival in the early 1930s. In the 1940s, many political prisoners from the occupied Western Ukraine and Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists were deported to the Far East, bringing fresh energy to the Ukrainian community there. However, since the 1950s, due to Russification, assimilation and further immigration of Russians, Ukrainian culture and communities in the Far East have gradually decayed.

Read also:

- “We’re against the Putin regime!” Fifth day of protests in Russia’s Far Eastern city of Khabarovsk

- Revision of History: How Russian historical propaganda justifies occupation of entire south-eastern Ukraine

- How Moscow hijacked the history of Kyivan Rus’

- Putin unintentionally highlights that Russia’s war on Ukraine is both ancient and fateful, Inozemtsev says

- Holodomor, Genocide & Russia: the great Ukrainian challenge

- The rise and decline of Donbas: how the region became “the heart of Soviet Union” and why it fell to Russian hybrid war