Her most well-known works include poetry collections On the Wings of Songs (1893), Thoughts and Dreams (1899), Echos (1902), the epic poems An Ancient Tale

(1893), A Single Word (1903), dramatic poems The Boyar Woman (1910), Cassandra (1903-1907), In the Catacombs (1905), and The Forest Song

(1911).

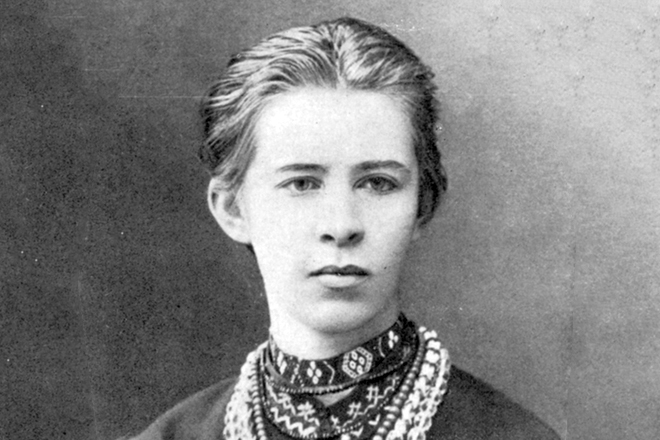

- In the family circle, Lesia Ukrainka was often called Larysa, Lesia, Zeya, Mysholosiya. Her mother called her Zeya, or Zeyichok, which comes from a sort of maize named “zea japonica” (referring to Lesia’s frailty). The name Mysholosiya was a combination of two names – Lesia’s and her older brother Mykhailo’s, with whom she was very close.

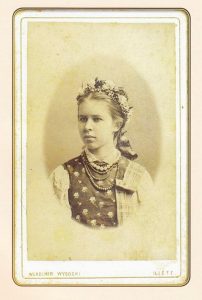

Lesia Ukrainka and brother Mykhailo Kosach - Little Lesia was stricken with bone tuberculosis in 1881. Due to her illness, she travelled to Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Egypt, and, several times, to Caucasia in search of a cure.

- As a child, she was afraid of the dark and carnivorous beasts, but struggled with her fears and often ran into the woods to search for benevolent “rusalky” (water nymphs and forest creatures).

- Lesia Ukrainka learned how to sew and embroider at the age of six and could spend hours sitting in a corner with her needle and thread. She presented her mother, father and brother Mykhailo with beautiful embroidery on their respective name days. She embroidered shirts, linens and “rushnyky” (decorated napkins) for her cousins, relatives and friends. Shortly before her death, she wrote to her mother that whenever she lacked the strength to write, she would lie on the sofa and embroider. One of Lesia’s embroidered shirts is exhibited in the Volyn Regional Natural History Museum.

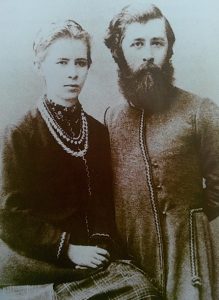

Mother Olena Pchilka (sitting) and Lesia Ukrainka, Yalta, Crimea, January, 1898 - The Kosach estate was located on the outskirts of the village. The family had 500 hectares of land, including forests, arable land and four hectares of gardens. In order to keep the estate in order, Lesia’s father hired workers from the nearby villages. Lesia had her own secret place on the family estate - a source and a well. An old willow, depicted in The Forest Song, once grew near the source. It is believed that the family treasure was buried somewhere on the former Kosach estate.

- At the age of nineteen, Lesia Ukrainka wrote a manual- The Ancient History of Oriental Peoples - for her younger sister.

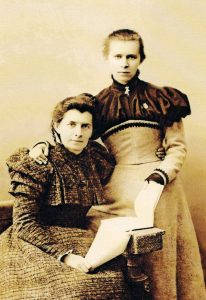

Lesia Ukrainka and sister Oksana Kosach-Shymanovska, 1906 - Lesia Ukrainka wrote only one poem in Russian, dated approximately 1899. She wrote it for Russian writer Grigoriy Machtet, who dared Lesia to write a poem in the Russian language. Lesia jokingly sat down at the piano and recited a poetic rondo off the top of her head - Impromptu (“Когда цветет никотиана”, When the nicotiana blossoms). The Russian writer was delighted. This was the first and last poem that Lesia wrote in Russian.

- Lesia Ukrainka’s first true love was a Marxist revolutionary from Belarus, Serhiy Merzhynsky. They met in Yalta in 1897, where both of them were undergoing treatment for tuberculosis. He was 27 years old, she was 26. He fondly referred to her as Lesia-Larochka. Serhiy died of lung tuberculosis in Minsk, with Lesia at his bedside. After his death in 1901, Lesia sat down and in one night wrote a poem entitled “Одержима” (Possessed).

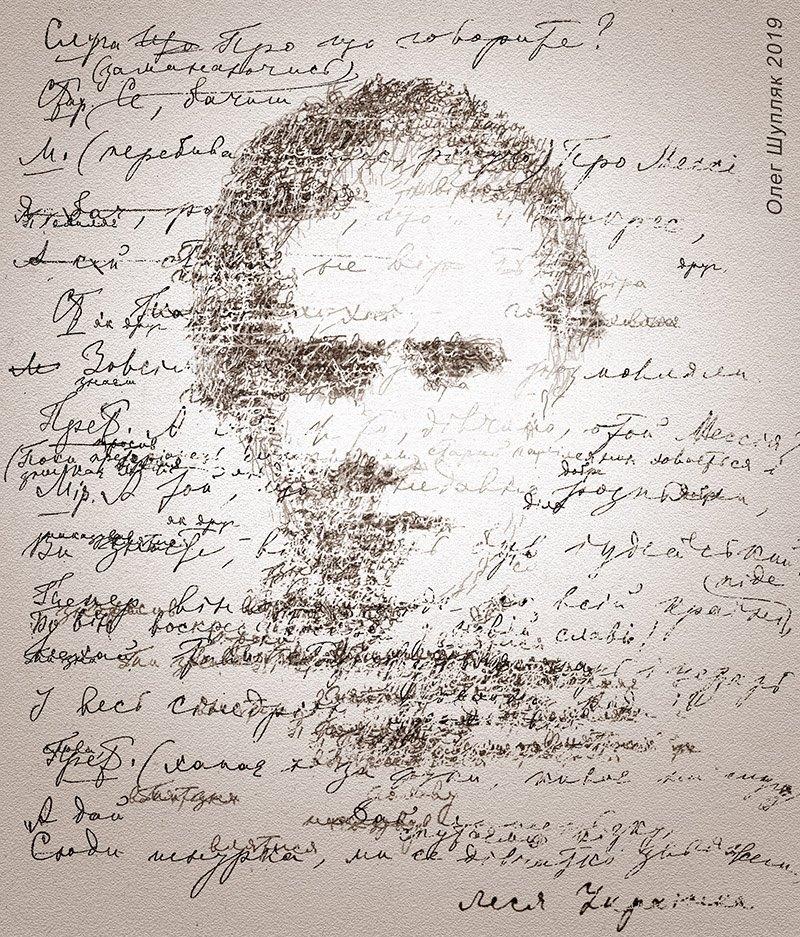

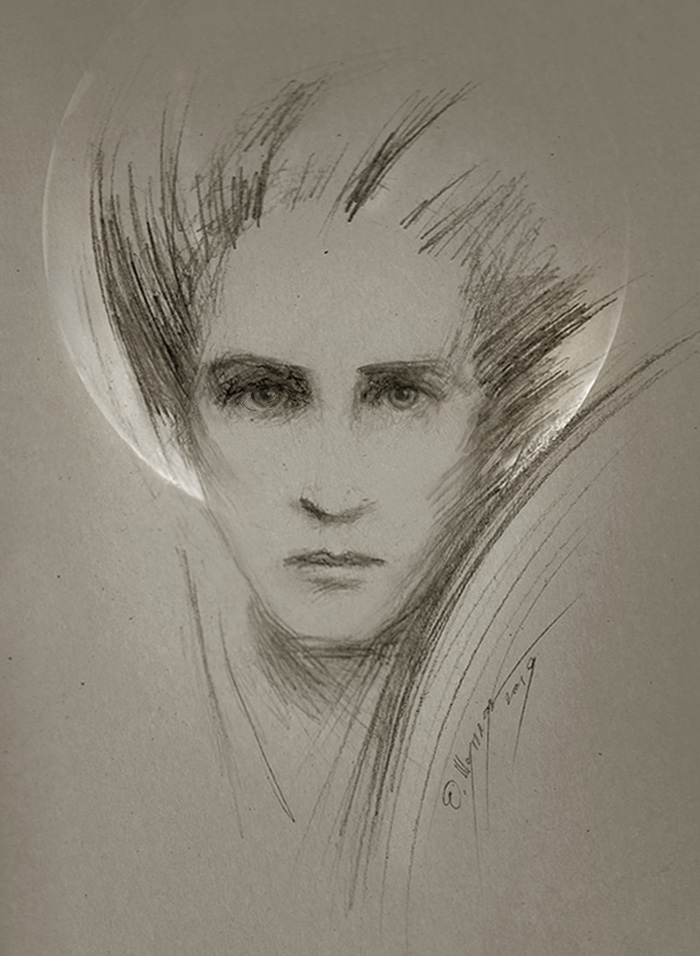

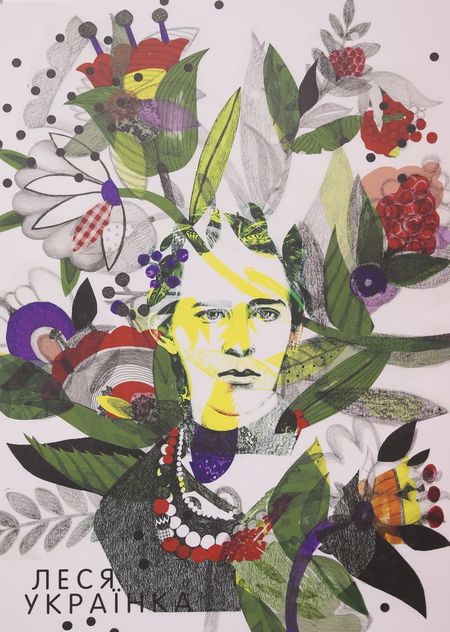

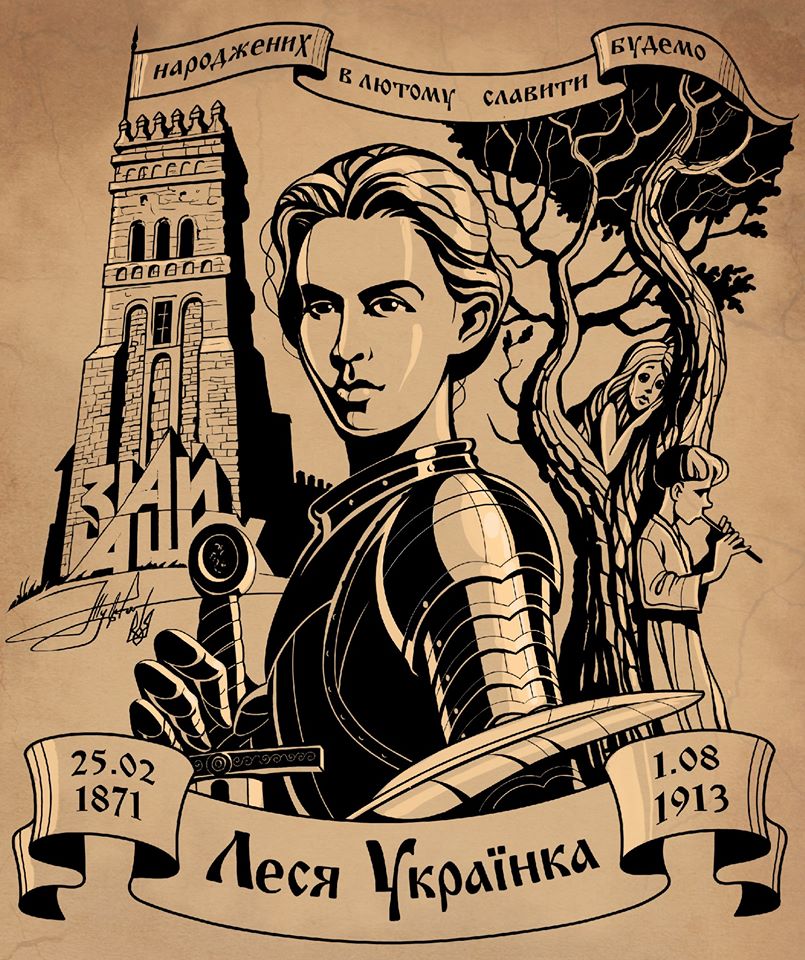

Maidan Lesia by Sociopath. Photo: Andriy Dubchak, RFE/RL Artist Oleh Shupliak Artist Oleh Shupliak Artist Dmytro Kryshovsky Artist Illya Stronhovsky Artist Polina Doroshenko Artist Yuriy Zhuravel Artist Yuriy Zhuravel Kyiv Street Art. Artist Yevhen Chystiakov - Lesia first met her husband Klyment Kvitka, who was ten years younger, in 1898. Her mother was strongly opposed to this union. However, Lesia was very strong-willed, renounced all financial assistance from her family and married the young Klyment in 1907. Klyment was very much in love with Lesia and tried hard to raise money for his wife’s treatment, selling his books and other collector items. Lesia was treated by the best doctors in Europe, but the disease continued to progress...

- Lesia Ukrainka made an invaluable contribution to Ukrainian folklore as a collector and performer of folk music. Her repertoire included traditional, Cossack and lyrical songs, lullabies, children’s songs, ballads, ritual chants, and, most unique of all, songs to fairy tales. In a letter to her uncle and spiritual mentor Mykhailo Drahomanov, Lesia Ukrainka claimed that “no one had as yet recorded any of the songs” that she had so lovingly collected over so many years.

Writer & feminist Olha Kobylianska (left) and Lesia Ukrainka - In 1888, when Lesia was just seventeen, she and her brother organized a literary circle called Pleiada, which promoted the development of Ukrainian literature and translation of foreign classics into Ukrainian. The organization was modelled on the French school of poetry, the Pléiade. The gatherings took place in different homes and were attended by Mykola Lysenko, Kostiantyn Mykhalchuk, Mykhailo Starytsky, and others. Pleiada was active until 1893. The poems and plays of Lesia Ukrainka are associated with her belief in Ukraine’s freedom and independence. Between 1895 and 1897, she became a member of the Literary and Artistic Society in Kyiv, which was banned in 1905 because of its relations with revolutionary activists.

Ukrainian literati at the inauguration of the monument to Ivan Kotliarevsky in Poltava, 1903. From left to right: Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, Vasyl Stefanyk, Olena Pchilka, Lesia Ukrainka, Mykhailo Starytsky, Hnat Khotkevych, Volodymyr Samiylenko - In February 1891, Lesia travelled to Vienna where she hoped to undergo an operation on her affected leg. However, the doctor refused to operate and told her to rely on her prosthetic apparatus and visit warm and dry countries. During her 40 days in Vienna, Lesia marveled at the freedom enjoyed by the Austrians as compared to the despotism of the Russian empire: “I look at the Europe and the Europeans before me, and I want to say something true even though I’m on the sidelines… My first impression was that I had entered another world - a better world, a freer world. It will be much harder for me now when I return to my country. I’m ashamed that we are so enslaved, that we carry such heavy shackles and sleep so peacefully under them. I have awakened, and I am sad and I grieve; I am in pain...”

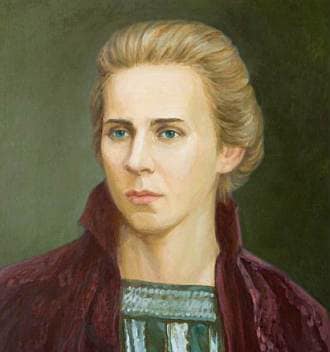

- In the last years of her life, Lesia Ukrainka’s eyes turned a spectacular light blue. Her eyes shone with an unearthly light, which amazed the people around her. This fact is mentioned in the memoirs published by Lesia’s younger sister, Isydora Kosach-Borysova.

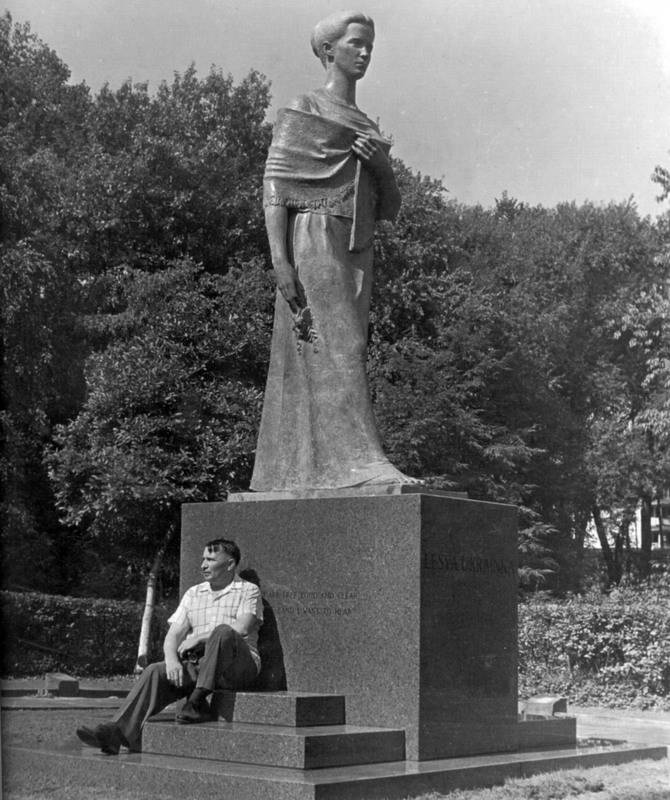

Last photo of Lesia Ukrainka, Kyiv, 1913 - Many official buildings and institutions have been named after Lesia Ukrainka. In addition, an asteroid, discovered on August 28, 1970, was named after the poetess (2616 Lesya). It is located in the main asteroid belt that lies between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter.

- We can only marvel at Lesia Ukrainka’s farsightedness and predictions about Ukraine and Ukrainians who “are by nature more sensitive, compliant and slow, while those accursed, brazen, aggressive and intolerant muscovites are of a much more impetuous and unpredictable disposition.”

Monuments dedicated to Lesia Ukrainka

Some prominent and prophetic quotes by Lesia Ukrainka:

It is shameful to bow and surrender to fate.

The gods are guilty for showing us the truth, but they did not give us the power to control the truth.

Whoever frees himself will remain free, but whoever tries to free someone else takes him into captivity.

A dark red cloud drew near, full of thundering fratricidal anger; it covered and destroyed the whole country. My soul froze and my heart went numb, and no words dared leave my mouth, for that country was mine.

It is from the hands of death that people receive immortality.

In the coming centuries, our language may become a mute, cold and strange corpse of silent words.

How lovely it would be to die like a falling star!

No! I live! And I will live forever! I have a heart that does not die.

My blade shall sever the iron chains of bondage and echo loudly throughout the abodes of all tyrants.