Even if the document did not factor in Ukraine’s latest achievements (the Index reflects progress between 2015 and 2016), it is still extremely alarming that Ukraine is not a leader of the Eastern Partnership. In one of the blocks for evaluation, Ukraine ranked third, below Georgia and Moldova, and in the other, it ranked second, following Moldova.

However, all indicators support the expectation that Ukraine’s position will change for the better in the next rating, which accounts for 2017.

The New Europe Center hosted an open presentation of the study’s results in Kyiv; here, we will tell about some interesting observations regarding the results of the Index.

Eurointegration after 2015: what has improved?

Skepticism aside, one may happily affirm that in the last three years Ukraine has advanced closer to Europe than it had in the previous twenty-three. Furthermore, Ukraine has done this during the most complex conditions of its independent history.

The most important advancements have been the ratification of the Association Agreement between Ukraine and the EU and the beginning of its implementation, as well as the acquisition of a functioning visa-free regime – despite Russian aggression and the crisis within the EU itself. The referendum in the Netherlands did not prevent ratification of the Association Agreement; neither did the Brexit nor the rise of Euroskeptic outlooks in a whole line of countries.

Ukraine began the reform of its justice system, it enacted new legislation regarding the civil service, it created a series of state agencies to fight against corruption and it implemented the ProZorro system of electronic state purchases and income declarations.

It is impossible to deny the evidence of positive changes.

The Euro-Integration Index confirmed that Ukraine is a leader among countries of the Eastern Partnership in measures such as freedom of speech and the independence of courts (the latter is a consequence of reform carried out in Ukraine in 2016). Generally, however, the three leaders in the index – Moldova, Ukraine, and Georgia – bear little difference in their rankings.

Ukraine holds the highest ranking among the six Partnership countries in the category “International Security, Political Dialogue, and Cooperation,” and this is Ukraine’s highest grade among all measured categories. This indicator above all reflects Ukraine’s integration into European Union security structures in a political manner (Ukraine is the only Eastern Partnership country which hosts annual summits with the EU, and it has the greatest number of reciprocal visits on the highest government levels.) Ukraine is also the regional leader in the categories “Sectoral Cooperation and Commerce” and “Adaptation to EU Norms.”

At the same time Ukraine, along with Azerbaijan, lags behind all other countries in the indicators of scientific and cultural exchange. This shows especially the discrepancy between Ukraine and other smaller countries of the Eastern Partnership over expenditure on science and cultural exchanges which the EU measures per capita.

The evaluation of the Business climate is a “cold shower.” But not only for Kyiv

Despite the Association Agreement, which includes the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement between Ukraine and the EU, Ukraine and Moldova fall behind the other Eastern Partnership countries in the indicators of favorability of business conditions. In the World Bank’s “Doing Business 2018” rating Ukraine ranked behind all other countries (!) of the Eastern Partnership. Among the six Partnership countries, Ukraine and Moldova do the worst job defending property rights and they have the least effective antimonopoly policies, disregarding that the Association Agreement requires the reform of the antimonopoly system.

Challenges in 2018

Today Ukraine has on its agenda the completion of many reforms – some within the framework of the Association Agreement, others beyond it – from the creation of an anti-corruption court to the continuation of reform of the judicial system to new reforms in the spheres of education, social security, land market reform and so on. New challenges also stand before the EU. Brussels has to find new methods to pressure the Ukrainian authorities after the “carrot” of the visa-free regime has been won.

Another obstacle to reform is the approaching election year when Ukraine traditionally experiences an increase of populism. Currently, this disorder is inherent not only in Ukrainian politics but in many countries of the EU as well. But in Ukraine’s case, populism’s influence is quite severe.

Ukrainians must remember that successful reform will aid their country’s partners in the West in discussions over such matters as the support of Ukraine’s territorial integrity and the sanctions against the Russian Federation as well as in matters of financial aid. Ukraine’s failures, it must be said, will harm not only Kyiv, but also Kyiv’s support in the EU – and above all, they will harm Ukraine’s reputation.

What does the Index Measure?

The index of European Integration of the Eastern Partnership has been published five times, beginning in 2011. It is a wide-scale investigation supported by the European Union.

The authors are members of the Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum, and the group is composed of representatives of all the countries of the Eastern Partnership: Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, Belarus, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Index of Euro-Integration of these countries is calculated based on six main categories: Democracy and Human Rights (a category which is further divided into 10 sub-categories); Adaptation to EU Norms; Sustainable Development; International Security, Political Dialogue and Cooperation; Sectoral Cooperation and Commerce; and Citizens of Europe (cultural, scientific, and educational cooperation).

For calculating the index experts gather available data (for instance, indicators from other international ratings) as well as “gray” data, which is calculated with the help of a specially developed algorithm. Apart from that, the Index includes text-based analysis about the countries and the categories through which the countries may be compared against each other. The most recent edition of the index covers data from 2015 to 2016, even though in the text sections experts touched upon the dynamics of 2017.

This is still the only product which allows one to answer that age-old question: “Are reforms being undertaken?”

As with every rating which attempts to measure complex reality with the help of numbers, the countries’ indicators do not always reflect all the nuances of their development. Therefore the text section, that is the narrative section of the index, is not less important than strict evaluations.

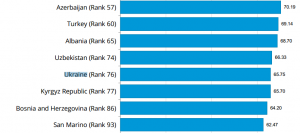

Accordingly, a high rank for one country or another does not mean that that country has markedly smaller problems. Likewise the highest theoretically possible indicator of “Rank 1” does not mean that an ideal has been reached, rather it corresponds to an analogous indicator from an average EU country (the developers of the methodology chose Lithuania as a “benchmark” country as it is one of the closest countries to those of the Eastern Partnership in its historical inheritance and the trajectory of necessary changes.)

The full text is of the study by New Europe Center is available here.

Read more:

- EU Eastern Partnership experts say Ukraine’s opening of KGB archives is exemplary

- EU could abolish roaming fees for Ukraine by 2020

- Intermarium – an idea whose time is coming again

- Ukraine now more supportive of NATO than Visegrad EU countries

- Ukraine’s European integration impossible without decommunization

- European values and Ukraine