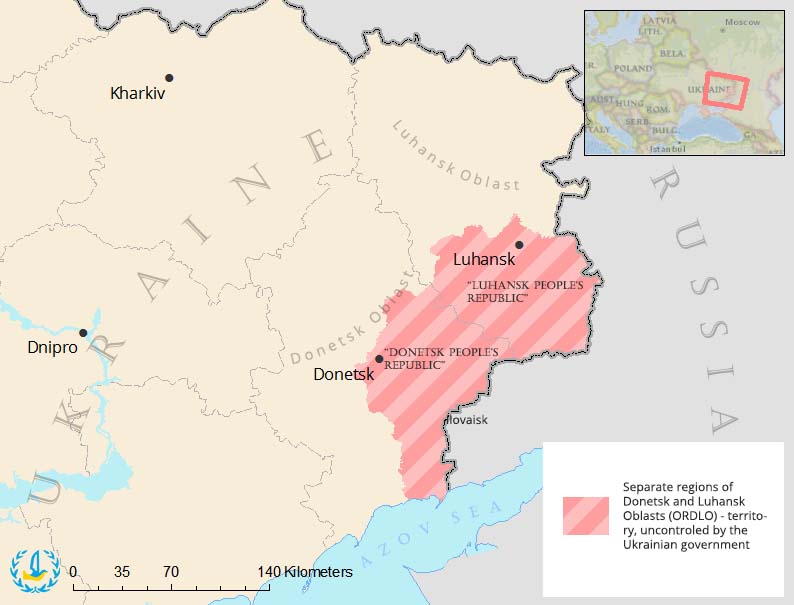

More than three years have passed since, in the aftermath of Euromaidan and occupation of Crimea, referendums under the gunpoint of Russian-hybrid troops were held in parts of eastern Ukraine. In result, two quasi-"states," the Luhansk and Donetsk "People's Republics" declared their independence from Ukraine, but de facto are no different from the Russian occupation zones in Georgia and Moldova. The war between the Russian-led militias of these territories, which in Ukraine are called Separate regions of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts (ORDLO), and Ukrainian forces, is attempted to be regulated by the Minsk agreements, and the future of these territories is still hanging in the air.

Have the three years that have passed alienated the population of the ORDLO, the mediasphere of which is full of relentless Russian or militant propaganda, from Ukraine? Does the ORDLO's population identify with their new identity as a self-proclaimed separate "country"? Or does the population living on the government-controlled and uncontrolled territories still constitute a single entity? A poll conducted by ZOiS in December 2016, but published only now, addresses these questions and finds that Ukraine hasn't "lost" uncontrolled Donbas yet. The survey, conducted by the German-based Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS), is based on 1,200 personal interviews in the controlled territory split evenly between Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, and 1,200 interviews by telephone in the uncontrolled territories.

Identity in flux

So far, the frontline running through Donbas hasn't alienated those living on both sides of it. Only 3-4% reported not having contact with their friends/family living on the other side of the front. In the "DNR-LNR," 18.8% are in daily contact with their friends/family living in government-controlled Donbas; in Donbas, 9.9% are.

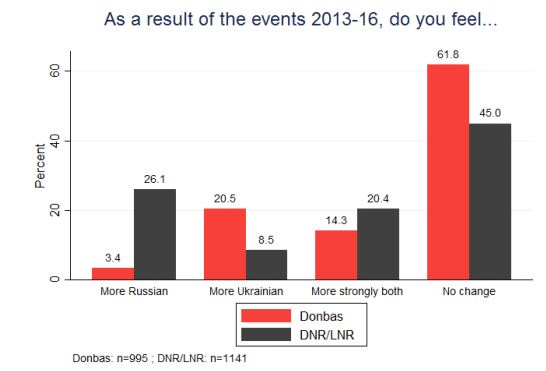

Only a quarter of those living in the "DNR-LNR" felt "more Russian," most did not experience any changes, and 8.5% felt "more Ukrainian." Apart from that, a significant number of respondents reported a mixed identity, "both Ukrainian and Russian."

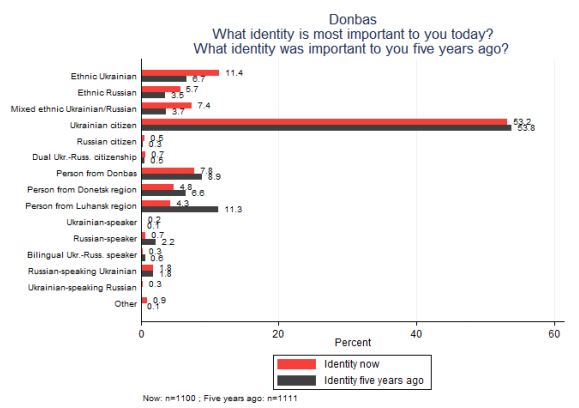

In government-controlled Donbas, ethnic self-identification has gone up compared to five years ago: more people feel ethnic Ukrainian (up to 11.4% from 6.7%), ethnic Russian, or both. Regional self-identification "person from Donbas, Luhansk, Donetsk region) has gone down. However, most of the people in Donbas still self-identify in civic categories, as Ukrainian citizens, and this number has remained almost unchanged (53.2%), although it is an identity in flux, with respondents also shifting from Ukrainian citizenship to Ukrainian ethnicity or a regional Donbas identity.

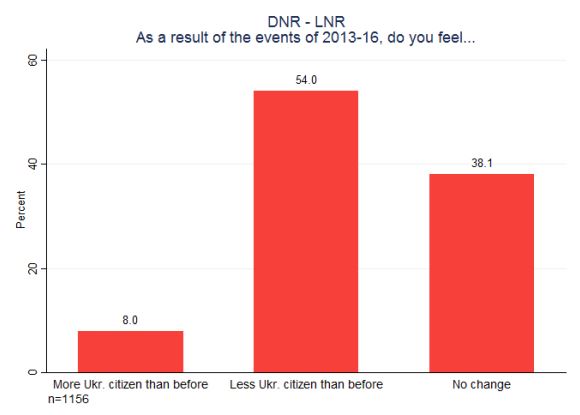

However, in the "DNR-LNR," it is the category of "Ukrainian citizen" that decreased the most. 54% reported that they felt less like Ukrainian citizens now compared to before 2013, and 38% reported no change. This identity is part of the price paid for the war in the occupied territories, ZOiS writes.

It's probable that a part of those that no longer self-identify as a Ukrainian citizen in the uncontrolled territories identify as a citizen of the "DNR," as a survey conducted by the Donbas Think Tank (albeit among only residents of the uncontrolled Donetsk Oblast) found in 2016. Unfortunately, ZOiS did not include questions on identification with the "DNR-LNR" in their questionnaires.

Future of "DNR-LNR," opinions about Russian media, Vladimir Putin, and Russian involvement in the war divides Donbas residents

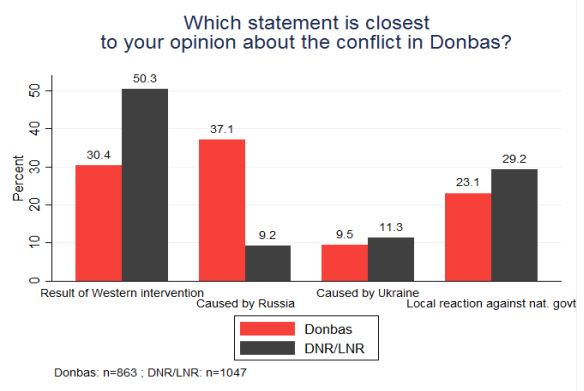

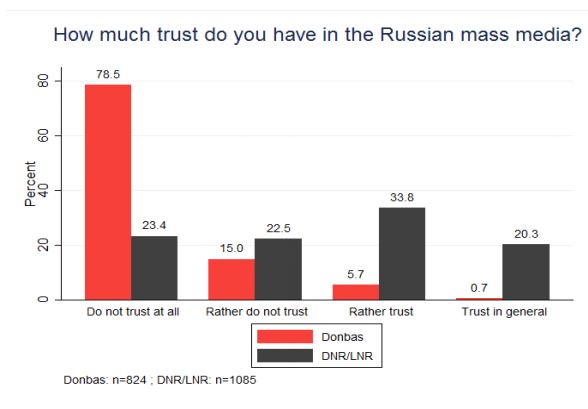

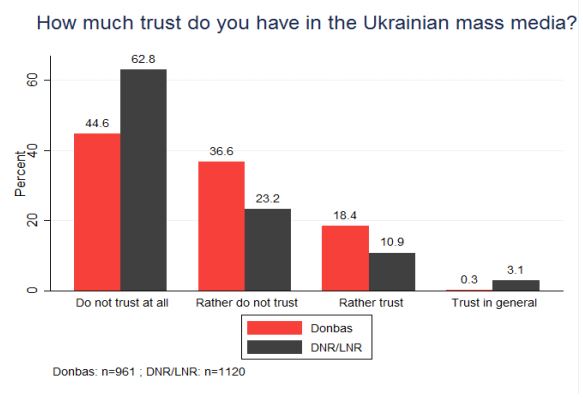

An interesting and unexpected result of the poll was that even on the uncontrolled territories most people don't blame Ukraine for the war in Donbas, with half seeing it as a result of "Western intervention" - one of the favorite topics for Russian propaganda - instead (in Ukrainian-controlled Donbas, 30.4% gave the same answer.) Unsurprisingly, opinions on the origins of the war in Donbas are quite different on both sides of the front: only 9.2% of people in "DNR-LNR" see the conflict as caused by Russia - after all, denial of Russian involvement in the war in Donbas is a key part of Russian propaganda, as opposed to 37.1% in government-controlled Donbas. And it is crucial for shaping the opinions of "DNR-LNR." Trust in Russian media is another thing that separates the residents of Donbas vs. "DNR-LNR:" only 6.4% respondents of the government-controlled areas trust it, vs. 54.1% in the "DNR-LNR."

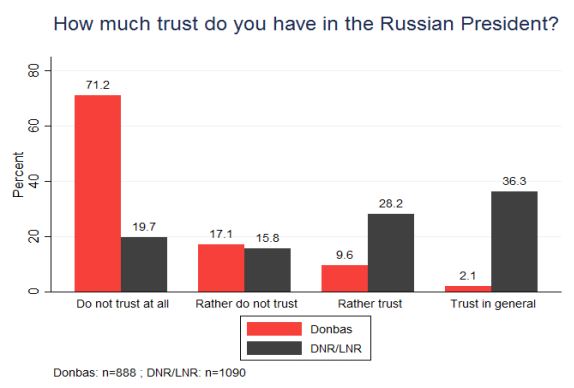

The statistics regarding trust in Russian President Vladimir Putin are strikingly similar to those of trust in Russian mass media. In the "DNR-LNR," 64.5% of respondents expressed varying degrees of trust in the Russian President, while 11.7% of respondents in government-controlled Donbas felt the same.

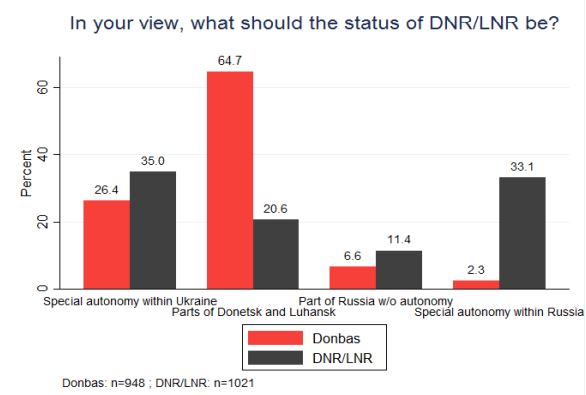

The frontline also divides the opinions of Donbas residents about the future of the "DNR-LNR." While most of the respondents in government-controlled Donbas answered they want the territories to return to Ukraine under the same conditions as before the start of the war, confirming the results of a recent poll by the International Republican Institute (IRI), which found that 73% of Ukrainians in the government-controlled regions of Donbas want the "DNR-LNR" to remain a part of Ukraine (although only 45% of those chose "part of Ukraine as before.") 44.5% of "DNR-LNR" respondents opted to join Russia, compared to 8.9% in government-controlled Donbas.

The above two graphs can be explained by the recent Russian policy shifts

, accompanied by media campaigns, indicating that Russia is preparing to recognize the independence of two puppet "republics:" the adoption of the Russian ruble, Russia's recognition of "passports" issued by the "DNR-LNR," and seizure of Ukrainian enterprises in the territories. This "independence," as seen as on the examples of Transnistria, South Ossetia, and Abkhazia, is little different from being treated as a Russian region.

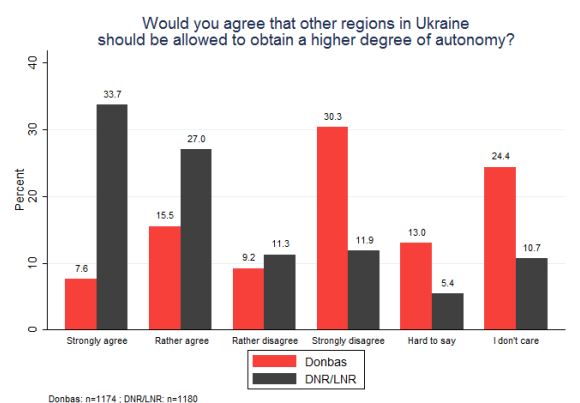

Views on the permissible degrees of autonomy of other Ukrainian regions is another issue on which residents of Donbas are divided. 60.7% of respondents in the "DNR-LNR," compared to only 23.1% in government-controlled Donbas (which, possibly, means this option has gotten less popular: the May-June 2016 poll by the Donbas Think Tank found that 46% of respondents in government-controlled Donetsk Oblast, and 68% in the "DNR," opted for a federation.

The last graph highlights another distinction between the two territories: the rising political apathy of residents of Ukrainian-controlled Donbas, reflected in the 24.4% who don't care about the political future of Ukraine, as well as in the 49.1% who are less interested in politics than three years ago.

What unites Donbas residents on both sides of the front

Despite the differences, there are many issues on which Donbas residents agree.

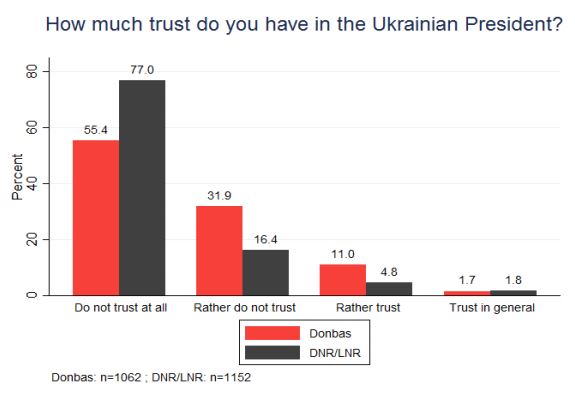

They are both suspicious of Ukrainian media and Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko.

They oppose Ukraine joining the EU and NATO. 72.1% in the Ukrainian-controlled territories oppose joining the EU and 82.5% oppose joining NATO, similarly to 81.8% opposing joining the EU and 93.1% opposing joining NATO in the "DNR-LNR." This contrasts with the average Ukrainian position, where 44% supported Ukraine joining NATO in 2016, and 55% supported

They oppose Ukraine joining the EU and NATO. 72.1% in the Ukrainian-controlled territories oppose joining the EU and 82.5% oppose joining NATO, similarly to 81.8% opposing joining the EU and 93.1% opposing joining NATO in the "DNR-LNR." This contrasts with the average Ukrainian position, where 44% supported Ukraine joining NATO in 2016, and 55% supported

joining the EU.

Both sides of the front display a lukewarm support for democracy, with 42% in government-controlled Donbas and 38.8% in the "DNR-LNR" agreeing it's the best form of government.

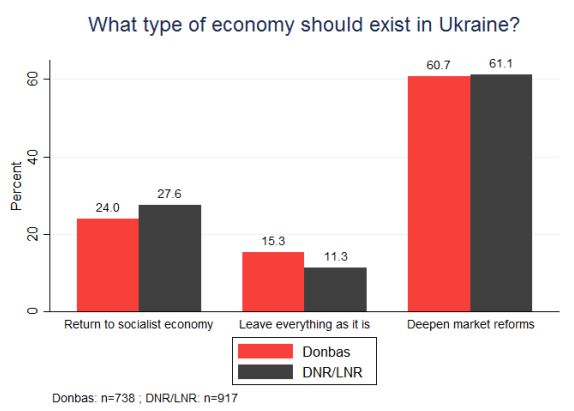

Interestingly, most respondents on both sides of the front support a free market economy in Ukraine.

All this leads ZOiS to conclude that the gap in attitudes between the two parts of the Donbas is not as clear-cut as one might have expected as a result of the increasing de facto separation of the "DNR-LNR" and the Kyiv-controlled Donbas. It would be premature for Kyiv to give up on the occupied territories, ZOiS concludes.

Gwendolyn Sasse, the author of the ZOiS report, considers it possible to compare the results of the face-to-face and telephone interviews, Obozrevatel reported. "I think that the telephone interviews even have an advantage. People feel safer answering the questions by phone than during face-to-face interviews under the conditions of war," she commented. However, she adds, "this method also has its drawbacks - due to wartime conditions, people can answer questions looking back at what answers are expected of them."

Obozrevatel adds that the phone numbers on uncontrolled territories were selected randomly, and the data sample was balanced by age, gender, and education level during the processing stage.

Read also:

- Only 18% identifies with Kremlin-backed “DNR” – survey

- Policy shift shows Russia preparing to recognize its puppet republics in Donbas

- Support for joining NATO at a historical high in Ukraine | Infographic

- Ukrainians overwhelmingly support European Integration | Infographics