Twelve years ago today, snipers opened fire on unarmed protesters walking up Instytutska Street in central Kyiv. Forty-eight people died on 20 February 2014 alone—the youngest was 17, the oldest 82. They were among the more than 100 protesters killed during the revolution, collectively remembered as the Heavenly Hundred.

Russia's full-scale invasion in 2022 shocked the world, but for Ukrainians, the war did not start then. It started in 2014, within days of the Revolution of Dignity's triumph, because Euromaidan posed a threat the Kremlin could not absorb. A democratic Ukraine—culturally and linguistically close to Russia—disproves Moscow's core claim that post-Soviet peoples need authoritarian rule.

That is why this war is Moscow's response to a revolution it could neither control nor reverse. Ukraine's General Staff stated it plainly: the Heavenly Hundred "were the first to take up the fight in the modern war for independence."

Yanukovych: Moscow's instrument

Viktor Yanukovych first came to power through a fraudulent election in 2004, triggering the Orange Revolution. He won legitimately in 2010 but quickly steered Ukraine back into Russia's orbit.

Two months after taking office, he signed the Kharkiv Accords, extending Russia's naval base lease in Crimea until 2042 and giving Moscow a permanent military foothold. The regime jailed opposition leader Yulia Tymoshenko on political charges. Transparency International named Yanukovych the top example of corruption in the world.

By late 2013, the EU Association Agreement was ready to sign. But after meeting Putin, Yanukovych abruptly reversed course, suspending the agreement for a $15 billion Russian bailout.

Why Euromaidan was more than an EU protest—and terrified the Kremlin

What followed was the largest democratic mass movement in Europe since 1989. On 21 November 2013, 1,500 people gathered on Kyiv's Maidan Nezalezhnosti; within days, hundreds of thousands joined them in cities across the country. As the Open Society Foundations noted, Euromaidan was "a rejection of injustice as a way of life." But it went far beyond the EU agreement. Small business owners protested tax laws favoring Yanukovych's oligarchs. The government had drained the National Bank's reserves. Russification policies were eroding the Ukrainian language in schools. These were separate grievances from separate groups—and that made the revolution impossible for Moscow to co-opt.

The Kremlin frames Euromaidan as a "western Ukrainian" revolt manipulated by the West. The data says otherwise: even in Ukraine's south and east, only 8.3% favored joining Russia, and 70% of easterners wanted the country to remain united. Russian-speaking Ukrainians—the people the Kremlin claimed as its own—chose Europe too.

The Yanukovych regime's crackdown

The regime responded with escalation: on 30 November, Berkut riot police brutally dispersed a peaceful student encampment, and 500,000 people showed up the very next day. Yanukovych rammed through "dictatorship laws" criminalizing protest. Russian FSB officers helped coordinate the crackdown, and authorities ordered the police assault hours after a $2 billion tranche of Russia's bailout arrived.

Between 18 and 20 February, security forces opened fire on the protesters. Over 100 people died; forensic investigations matched bullets to Berkut assault rifles. On 21 February, Yanukovych fled to Russia.

Russia invades—before the "coup" even happens

The Kremlin sells two myths: that Euromaidan was a "Western coup," and that the war in Donbas was a "civil war" between Ukrainians. The timeline demolishes both.

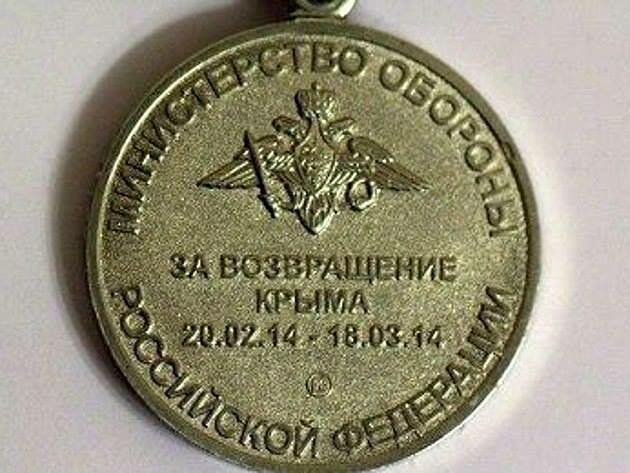

In December 2013—months before Yanukovych even fell—Crimean parliament chairman Vladimir Konstantinov told Russia's Security Council chief that Crimea was ready to join Russia if the president lost power. In January 2014, Russian oligarch Konstantin Malofeev traveled to Crimea with former FSB officer Igor Girkin. Before Yanukovych was even removed, the Kremlin received a strategy paper outlining annexation. The Russian Defense Ministry later minted a medal for the "return of Crimea" dated 20 February 2014—two days before the supposed "coup."

By late February, Russian soldiers without insignia had seized Crimea's parliament, airports, and military bases. By April, Girkin led armed men from Russia into Donbas, igniting the war the Kremlin would call a "civil conflict"—though it was planned in Moscow, led by a Russian officer, and fought with Russian weapons.

Before Yanukovych was even removed, the Kremlin received a strategy paper outlining annexation. The Russian Defense Ministry later minted a medal for the "return of Crimea" dated 20 February 2014—two days before the supposed "coup."

What Euromaidan built—and what Putin targeted

Trending Now

The revolution produced a decade of transformation. Post-Euromaidan governments built an anti-corruption architecture unprecedented in the post-Soviet space: the National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU), a specialized High Anti-Corruption Court, and the Prozorro open procurement system. Decentralization relocated budgets from Kyiv to local municipalities. Decommunization replaced Soviet monuments and street names with Ukrainian ones.

Three days before ordering the invasion, Putin made clear these institutions were the problem. In his 21 February 2022 speech, he named NABU, the Anti-Corruption Prosecutor's Office, and the High Anti-Corruption Court—calling them instruments of Western control: "All this is done under the noble pretext of invigorating efforts against corruption. All right, but where are the results? Corruption is flourishing like never before." He threatened to reverse decommunization too: "You want decommunization? Very well, this suits us just fine. But why stop halfway?"

As the US Institute of Peace noted, Putin cited these bodies' very existence as justification for invasion.

Ukrainians saw these institutions quite differently from Putin. When their own government tried to curb NABU and SAPO's independence in July 2025, thousands took to the streets in the first major wartime protests, forcing the law's reversal within days. The institutions Putin dismissed as Western puppets were ones Ukrainians fought to protect.

Perhaps most striking was the language shift: Russian speakers at home dropped from 40% in 2011 to 15% by 2022—a largely grassroots change. For the Kremlin, this was the ultimate proof that Ukraine was lost.

The war that never paused

Between 2014 and 2022, some 14,000 people died in the Donbas along a front line that never truly fell silent. The Minsk agreements froze the contact line but resolved nothing—and both sides later admitted as much. In December 2022, Merkel told Die Zeit that Minsk was "an attempt to give Ukraine time." For Moscow, the problem was exactly that: Ukraine was not collapsing. It was building institutions, reforming its military, and moving steadily westward.

As the Carnegie Endowment noted, Russia's control over occupied territories "was always secondary to its desire to dictate Kyiv's decisions." When eight years of proxy war failed to break Ukraine's trajectory, Putin escalated—not from strength, but because the Euromaidan transformation was succeeding and his window was closing.

"You want decommunization? Very well, this suits us just fine. But why stop halfway?"—Vladimir Putin, 21 February 2022

Russia's 2022 invasion is not a new war—it is the escalation of the same one. A thriving democratic Ukraine remains the thing Putin's system cannot survive.

Treat this as a war that started in 2022, and you miss its real cause: Russia's desire to crush Ukrainian democracy. The Heavenly Hundred who fell on Instytutska Street were its first casualties. The tens of thousands killed since are their successors in the same fight.

Read also

-

The revolution that refused to be crushed: how Ukraine’s Euromaidan defied Russia’s subterfuge

-

“Existential fight against Russia’s tyranny”: Ukraine, international diplomats honor Euromaidan Revolution fallen heroes

-

Ten years after Euromaidan, Russia tries to erase Ukraine’s national revival

-

With the Maidan, Ukraine fought off Moscow not when empire was weak but when it was strong, Babchenko says