In a single week in February 2026, three things happened on the same continent. China’s Xi Jinping announced zero tariffs for 53 African nations. Bloomberg published an investigation revealing Russia’s Orthodox Church had expanded to at least 34 African countries in under three years.

Africa has become the site of a three-front competition that is compounding pressure on Ukraine from two directions simultaneously.

And at the Munich Security Conference, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi pledged energy aid to Ukraine—while Chinese-made engines continued powering Russian drones that strike Ukrainian cities every night.

Each story was reported separately. Together, they reveal something none of them showed alone: Africa has become the site of a three-front competition that is compounding pressure on Ukraine from two directions simultaneously—Russian soft power and Chinese economic gravity—with no comparable counter-pull from Kyiv.

The continent holds 54 seats at the General Assembly.

The cost is measurable. When Russia launched its full-scale invasion in March 2022, 28 African countries voted in favor of the UN General Assembly resolution condemning the aggression, with only Eritrea voting against. By the February 2025 UNGA vote, that number had collapsed to 10, while eight African countries now actively vote against Ukraine, up from one.

The continent holds 54 seats at the General Assembly. That shift is not background noise—it maps directly onto the influence systems Moscow and Beijing have built.

Russia builds trust, then exploits it

Bloomberg’s investigation into the Russian Orthodox Church in Africa documented what amounts to a parallel diplomatic network. The church grew from four African countries to at least 34 since 2022, registering 350 parishes and 270 clergy. Russian Houses—cultural centers offering language courses and community programming—now operate across seven African countries with more planned.

Scholarships bring students to Russian universities, language courses build cultural familiarity, churches create community trust, and state media shapes the narrative.

Russian state-run news agency Sputnik is opening its second African bureau in South Africa, following its launch in Ethiopia in early 2025. Russia allocated over 5,300 scholarships to African students, nearly triple the 2020 figure.

The expansion follows a deliberate pattern: scholarships bring students to Russian universities, language courses build cultural familiarity, churches create community trust, and state media shapes the narrative. Tom Southern of the Centre for Information Resilience called it “spiritual colonialism.”

South Africa, Kenya, and Botswana have all opened investigations into how their citizens ended up in Russia’s war machine.

But that trust infrastructure doesn’t just generate goodwill—it generates recruits. Russia has drawn fighters from about 35 African countries, with Ukraine estimating more than 1,400 Africans now fighting for Moscow. The All Eyes on Wagner research group identified roughly 300 Africans killed in combat for Russia.

Young women from Uganda, Rwanda, Kenya, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria were lured to Russia’s Alabuga Special Economic Zone under promises of hospitality work—and found themselves assembling Shahed attack drones in a sanctioned military factory. South Africa, Kenya, and Botswana have all opened investigations into how their citizens ended up in Russia’s war machine.

China adds economic gravity

If Russia offers cultural alignment, China offers something harder to refuse: market access. Xi’s zero-tariff offer to 53 African nations arrived as many were seeking alternatives to Trump-era tariffs—with a single, pointed exclusion: Eswatini, the last African state recognizing Taiwan. Access exchanged for alignment.

For Ukraine, the danger isn’t that Chinese tariffs are coordinated with Russian churches. It’s that they compound. A country receiving Russian Orthodox priests, Russian scholarships, and Chinese duty-free access has multiple separate reasons to distance itself from Kyiv at the UN—and no comparable incentive pulling the other way.

Beijing’s role is further complicated by the fact that the same week Wang Yi pledged energy aid to Ukraine, US officials estimated China provides nearly 80% of the sanctioned components sustaining Russia’s military campaign—electronics, optics, navigation systems.

China offers Africa access to the world’s second-largest economy. It offers Russia the means to wage war. It offers Ukraine humanitarian aid. All three at the same time, and none of it accidental.

Ukraine’s counter-strategy: real but outgunned

Ukraine is present in Africa—and not just diplomatically. Since 2022, Kyiv has nearly doubled its embassies on the continent to 18, with plans to reach around 20—potentially more than any other Central-Eastern European state, as Defence24 recently noted.

President Zelenskyy’s April 2025 visit to South Africa was described by both sides as historic. A Centre for Global Ukrainian Studies was established at the University of Pretoria, and the “Grain from Ukraine” humanitarian program has provided food security for 8 million people across ten countries, as The Kyiv Independent reported in 2024.

The Africa Corps profits from insecurity. It has no incentive to solve it.

All three competitors have military footprints on the continent—but they are different in kind. Russia’s Africa Corps, the successor to Wagner, maintains roughly 6,000 operatives across the Sahel and Central Africa. But in July 2025, the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT) report documented a consistent pattern: state capture, mass civilian targeting, and deliberate prolonging of instability for profit.

In Mali, Russian operatives and national forces massacred over 500 people in Moura in 2022—the worst single atrocity in the country’s decade-long conflict. The Africa Corps profits from insecurity. It has no incentive to solve it.

China’s military presence is growing fast. The Africa Center for Strategic Studies reported that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) conducted three military exercises in Africa in just 18 months, each marking a qualitative shift—including its largest-ever deployment on the continent.

Trending Now

Ukraine’s military engagement is different—and more complicated than its diplomatic messaging suggests.

The PLA Navy made at least 15 African port calls in 2024–2025, exceeding all previous annual totals. China has become the leading arms supplier in West Africa, including to sanctioned Sahel juntas—putting Beijing at odds with African Union (AU) and ECOWAS norms against unconstitutional seizures of power.

Ukraine’s military engagement is different—and more complicated than its diplomatic messaging suggests. From 1996 to 2022, Ukrainian forces served in UN peacekeeping operations across seven African countries—Angola, Sierra Leone, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia, Sudan, Côte d’Ivoire, and Mali.

Two diplomatic relationships lost for a tactical embarrassment of Wagner that did nothing to weaken Russia’s war machine in Ukraine.

They repaired roads, ran medical evacuations, conducted reconnaissance, and trained alongside African forces under multilateral mandate. Those deployments built genuine local capacity rather than dependency or extraction.

Since 2022, Ukraine has gone further—and not always to its benefit. Ukrainian special forces have reportedly conducted operations against Russian mercenaries in Sudan. And in July 2024, Tuareg rebels inflicted Wagner’s heaviest known defeat in Africa at Tinzaouaten in northern Mali, killing some 80 mercenaries and 47 Malian soldiers.

A spokesman for Ukraine’s military intelligence implied Kyiv provided intelligence support to the rebels. Mali severed diplomatic relations with Ukraine immediately; Niger followed. ECOWAS condemned outside interference. Senegal summoned Ukraine’s ambassador.

Kyiv later denied involvement—but the damage was done. Two diplomatic relationships lost for a tactical embarrassment of Wagner that did nothing to weaken Russia’s war machine in Ukraine.

The Ukrainian Prism report argues persuasively that Ukraine’s engagement with South Africa—a BRICS member, African Union leader, and 2025 G20 president—has shifted from “managed distance” to genuine dialogue. Four rounds of political consultations have been held since 2022, and cooperation on child protection and nuclear safety has begun.

Ukraine has 18 embassies, a university center, and the credibility of having served under blue helmets for two decades.

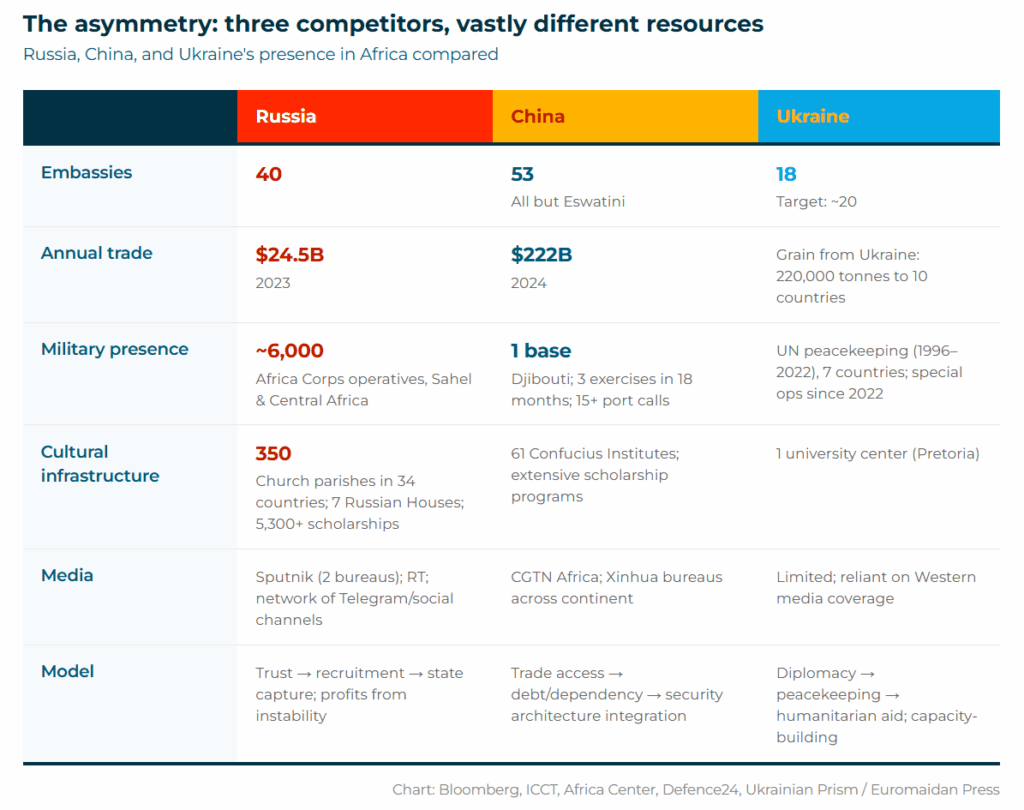

But the asymmetry remains stark. Russia has 40 embassies, 350 parishes, 6,000 paramilitary operatives, and a state media network across the continent. China has $222 billion in annual trade, a naval base in Djibouti, and the PLA’s most ambitious African exercises in history. Ukraine has 18 embassies, a university center, and the credibility of having served under blue helmets for two decades—credibility now complicated by Tinzaouaten.

What the pattern suggests

The three-front competition won’t be won by matching Russia and China resource for resource. But the pattern points to three shifts that could change the trajectory.

The Bloomberg investigation provides the evidence for the first: the same country opening churches in African communities is recruiting their citizens for drone factories and sending their young men to die in Russian trenches.

The logic is straightforward: if Ukraine’s African strategy has a center of gravity, it’s Pretoria—and the relationship has never been warmer.

That connection—between trust infrastructure and exploitation—has not been made visible enough to African publics. Ukraine’s strategic communications in Africa, which the Prism report acknowledges have improved since 2022, could drive it home relentlessly and specifically.

The second involves South Africa. Pretoria’s influence in the AU, BRICS, and the G20 makes it the single most consequential African partner for Ukraine. The Prism report recommends formalizing a Joint Commission on Political and Economic Cooperation and linking Ukraine’s Peace Formula to G20 recovery themes. The logic is straightforward: if Ukraine’s African strategy has a center of gravity, it’s Pretoria—and the relationship has never been warmer.

The third concerns the military distinction. All three competitors have soldiers in Africa. Russia creates dependency and profits from instability. China is pulling African states into Beijing’s security architecture. Ukraine has built roads, organized evacuations, and left behind capacity—until Tinzaouaten muddied the picture.

The ground shifted not because African countries support Russia’s war, but because Moscow and Beijing built systems that reward distance from Kyiv.

For African governments caught between a mercenary force that massacres civilians and a superpower angling for bloc integration, a partner that builds genuine defense capacity under a multilateral mandate remains something neither Moscow nor Beijing can offer.

But deploying that distinction as a strategic asset requires Ukraine to decide what its African military engagement actually is: peacekeeping partner, or covert combatant against Russian proxies. Trying to be both cost Kyiv two embassies in a week.

Africa holds 54 UN votes, a quarter of the General Assembly. In March 2022, 28 African countries stood with Ukraine. By February 2025, ten did—and eight voted against. The ground shifted not because African countries support Russia’s war, but because Moscow and Beijing built systems that reward distance from Kyiv.

Ukraine has begun building counter-systems of its own. Whether they can outpace what Russia’s 350 parishes and China’s $222 billion have already built is the open question—and the stakes are not abstract.