There are no quick fixes for Ukraine’s energy crisis. The thermal plants are gone, winter is here, and the blackouts will continue.

But could wind energy offer a slow fix?

“The question isn’t ‘will we survive this winter?’” former Naftogaz CEO Andriy Kobolyev wrote in Liga.net this week. “The question is: how?”

His answer points to what’s already working—and what isn’t. The centralized Soviet-era systems are failing. Distributed generation is surviving.

The gap between what wind energy could contribute and what policy allows is widening.

Ukraine added 324 MW of wind capacity in 2025—more than the 248 MW built during the previous two years of war combined, the Ukrainian Wind Energy Association (UWEA) announced in December. Seven wind farms are under construction. A turbine factory now operates in western Ukraine. And 4 GW of projects are ready to be built.

Yet Kyiv residents face as little as three hours of electricity per day this January. The gap between what wind energy could contribute and what policy allows is widening.

Why wind farms survive

Russia has begun targeting wind turbines with FPV drones—several were destroyed at the Kramatorsk wind farm in October. But destroying one turbine leaves hundreds operational. The same strike on a thermal plant blacks out entire oblasts.

Before the war, wind generated around 4% of Ukraine’s electricity—a small share, but one produced by infrastructure spread across dozens of locations rather than concentrated in a few massive plants.

Decentralization already works

Kobolyev points to self-sufficient cities, businesses, and households that switched to small-scale autonomous systems and alternative fuels in previous years. The city of Zhytomyr is one example. These distributed systems are surviving what centralized infrastructure cannot.

Ukraine had the resources to protect its centralized infrastructure. It chose not to.

Then there’s Energoatom. Kobolyev calls it “an epic failure across a whole range of directions”—singling out the “actual absence of protection systems at connection points of nuclear plants to the grid, which would be proportionate to the financial capabilities of this state monster.”

Why does Ukraine’s grid survive missiles that would black out Europe? Ousted energy chief explains

The implication: Ukraine had the resources to protect its centralized infrastructure. It chose not to. Now that infrastructure lies in ruins, distributed alternatives offer a template for rebuilding.

Wind energy: distributed, privately owned, hard to knock out with a single strike.

“If even one of [the necessary] conditions isn’t met, you need to switch to distributed small-scale systems in private ownership,” Kobolyev wrote. His two conditions for centralized Soviet-era systems to work: no corruption, and no risk of Russian missile strikes. “If both conditions fail simultaneously, well—we’re seeing the result in a whole range of Ukrainian cities.”

Wind energy fits this model exactly: distributed, privately owned, hard to knock out with a single strike.

The math of loss

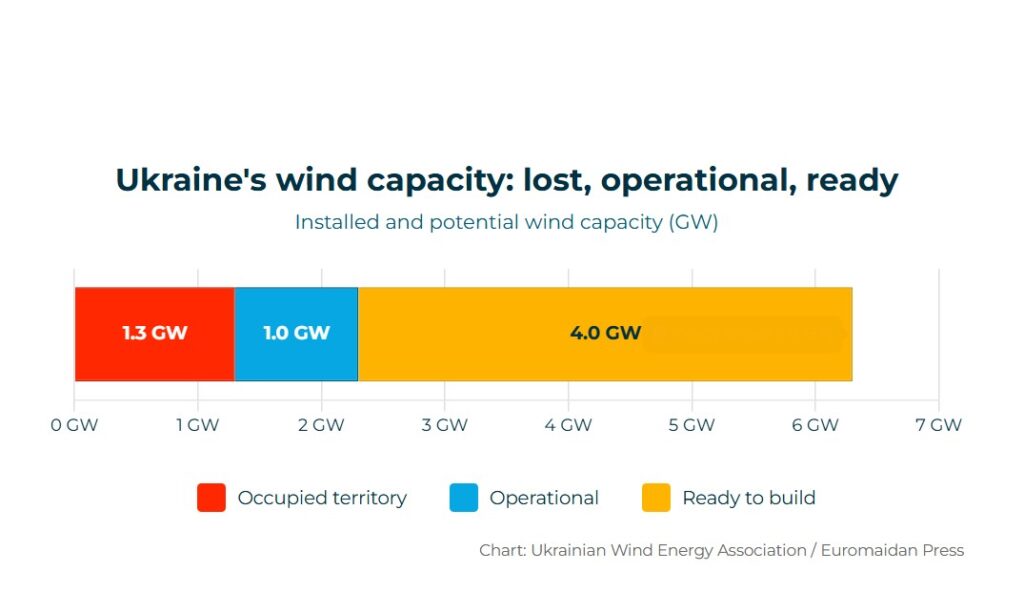

Ukraine’s total installed wind capacity stands at 2.3 GW. More than half—1.3 GW—now sits on occupied territory, according to UWEA.

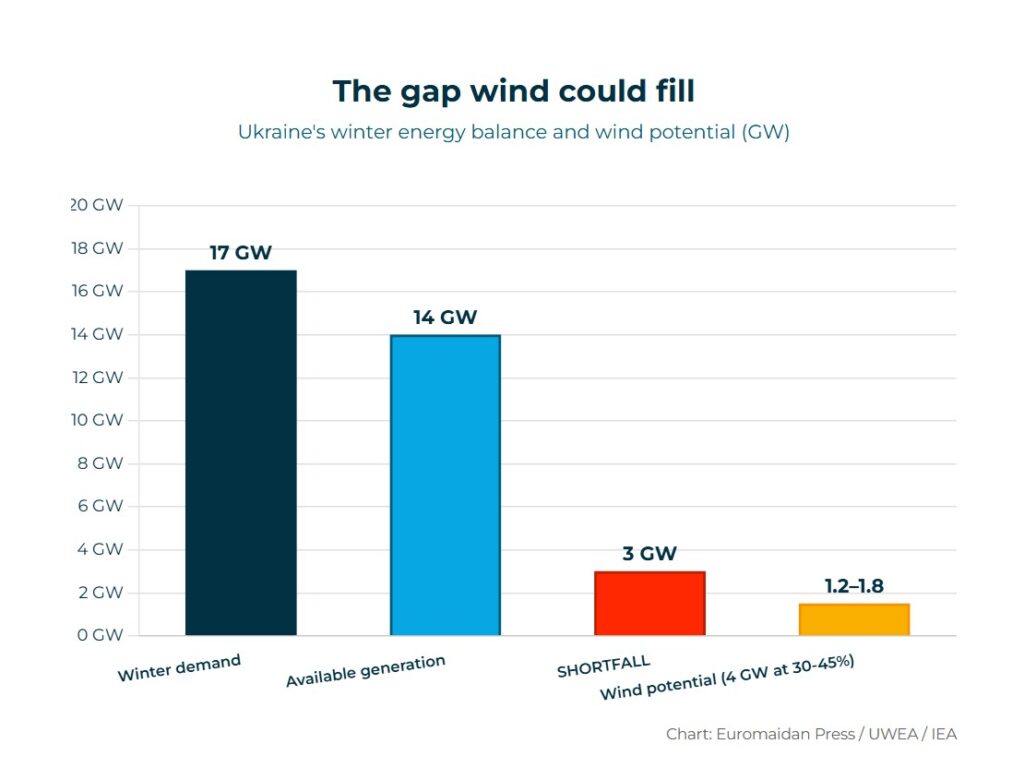

The 324 MW built this year covers roughly 11% of Ukraine’s current 3 GW shortfall between available generation (14 GW) and cold-weather demand (17 GW). Even if all 4 GW of ready projects were built tomorrow, they wouldn’t close the gap entirely—and wind doesn’t blow on demand.

“The old Soviet equipment being destroyed should be replaced with modern, decentralized installations.”

“The old Soviet equipment being destroyed should be replaced with modern, decentralized installations—solar, wind, battery storage—that don’t depend on imported gas and are harder to knock out with a single strike,” energy experts Kateryna Kontsur and Oleh Savytskyi wrote in Euromaidan Press last week.

A factory waiting for orders

A turbine factory in Zakarpattia Oblast is now operational—relocated from Kramatorsk, where it once produced Ukraine’s most powerful wind generators, 45 km from the front line. Friendly Wind Technology, Ukraine’s only manufacturer of multi-megawatt turbines, can build up to 20 units per year at 4.8–5.5 MW each—and plans to triple that capacity to 100 turbines annually by early 2026.

It could produce more. There aren’t enough buyers.

The domestic factory gets no comparable support.

Trending Now

DTEK, Ukraine’s largest private energy company, owned by the billionaire Rinat Akhmetov, secured €370 million ($430 million) in financing backed by Danish Export and Investment Fund (EIFO) to purchase 64 Vestas turbines for its 384 MW Tylihulska expansion in the Odesa Oblast—Europe’s biggest wartime wind project.

The Danish turbines are larger (6 MW each versus the domestic 4.8–5.5 MW), but the financing matters more: Danish state guarantees de-risked the investment in ways Ukrainian banks cannot match. The domestic factory gets no comparable support.

“The market is not open for independent renewable energy project developers.”

“Only the most resilient and politically connected companies are able to survive and continue business,” Savytskyi, an energy policy expert at Razom We Stand, told Euromaidan Press. “The market is not open for independent renewable energy project developers.” He called Ukraine’s energy policy under President Zelenskyy a “total failure.”

The structural barriers are well-documented: market debts prevent new investors from getting paid, no long-term contracts guarantee buyers for the electricity produced, and regulatory obstacles favor established players.

UWEA head Andriy Konechenkov confirmed at a December press conference that debts and lack of long-term buyers remain the sector’s main constraints. Environmental groups have also opposed some Carpathian projects, adding another friction point. But the government is starting to respond.

Signs of movement

On 19 January, Minister of Energy Denys Shmyhal ordered Ukrenergo to improve power transmission between western and eastern Ukraine—faster construction of EU interconnectors, simplified connections for distributed generation, reduced bureaucracy, and protected substations near the front line.

Some experts want to go further. Savytskyi and co-authors proposed, in a Green Deal Ukraїna report, building renewable capacity in neighboring EU countries and importing power through existing transmission lines. As the report mentions, DTEK previously used the 220 kV line at Dobrotvir to export coal-fired electricity to Poland. It could work in reverse.

Reaching any of these targets would require opening the market.

The scale of what’s needed, however, dwarfs current efforts. The International Energy Agency recommended in 2024 that Ukraine install 11 GW of additional wind capacity by 2030. Ukraine’s own National Energy and Climate Plan targets 6.1 GW. The country currently has just 534 MW of battery storage—helpful in balancing intermittent wind, but a fraction of the 5.6 GWh the IEA says Ukraine needs.

Reaching any of these targets would require opening the market to independent developers, clearing the debt backlog, and creating purchase agreements that give investors confidence.

The verdict: A viable slow fix—if the market opens

Wind energy won’t save Ukraine this winter. But the numbers suggest it could make a real difference by the next one—if policy catches up.

Consider: Ukraine’s current shortfall is 3 GW. There are 4 GW of wind projects ready to build. Wind doesn’t blow constantly—new onshore turbines in Ukraine operate at 30-45% capacity—so 4 GW of installed capacity translates to roughly 1.2–1.8 GW of average output. That’s not full coverage, but it’s 40-60% of the gap, from infrastructure that Russia struggles to destroy.

The domestic factory plans to build 100 turbines per year by 2026. At 5 MW each, that’s 500 MW annually from Ukrainian-made equipment alone. Add internationally-financed projects like DTEK’s 384 MW Tylihulska expansion, and Ukraine could plausibly reach 800 MW or more per year.

Only politically connected companies like DTEK can navigate the system.

The International Energy Agency recommends 11 GW of additional wind by 2030. Ukraine’s own plan targets 6.1 GW. Either is achievable—the projects exist, the factory is scaling, the technology works.

What doesn’t work: the market. Debts prevent new investors from getting paid. No long-term contracts mean no financing for independent developers. Only politically connected companies like DTEK can navigate the system—and even they rely on Danish state guarantees.

All in all, wind energy is a viable but slow fix.

Shmyhal’s 19 January order addressed grid connections but not market access. Until someone clears the debt backlog and creates purchase agreements, 4 GW of wind capacity will keep sitting idle while Ukrainians freeze.

All in all, wind energy is a viable but slow fix. Whether Ukraine chooses to use it is a policy question, not a technical one.