- In 2025, the Russians mostly stopped using armored vehicles

- It's not that they lack vehicles: they've pulled many thousands from long-term storage

- No, the Russians have de-mechanized because infantry tactics work better

- The infantry can slip past drones that easily spot approaching vehicles

- But Russian infantry casualties are mounting as they bear the brunt of the fighting

In 2025, the Russian armed forces in Ukraine traded vehicles for infantry. What was once among the world's leading mechanized armies with tens of thousands of armored vehicles of all types instead became an army that mostly marched into battle on foot.

It was a costly new doctrine for the Russians: potentially around 100,000 Russian troops died—probably more than in any of the three previous years.

But it worked. The Russians advanced, and at a faster pace than before.

Will the new doctrine work again this year? There are reasons to be skeptical. Namely, the terrain Russia will fight on in 2026 is much different than the terrain it fought on in 2025 —and it may favor Ukraine.

When did Russia park its vehicles?

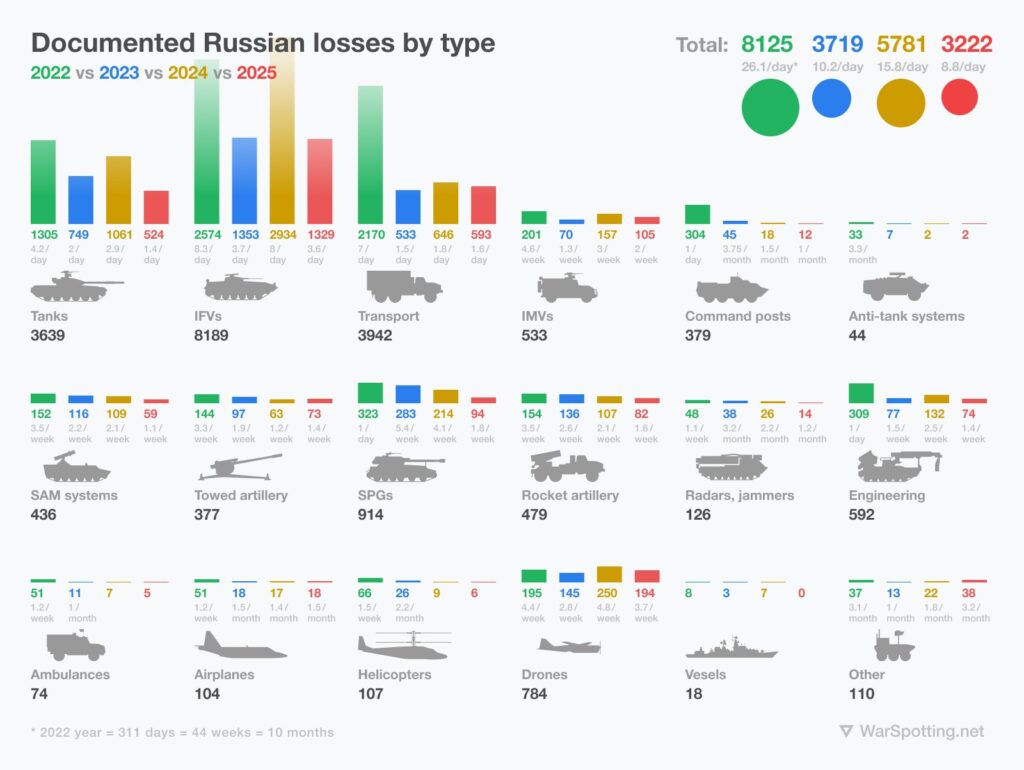

Looking back 12 months, the open-source analysts at Warspotting identified the moment the Russians parked their vehicles. "Something changed starting late April/early May," the group explained.

In those few weeks, daily Russian vehicle losses dropped by half to fewer than eight per day. The decline coincided with the culmination of Russia's successful counteroffensive that ejected Ukrainian forces from Kursk Oblast in western Russia following a nine-month battle.

Eight vehicle losses a day for seven months through the end of 2025 marks the lowest sustained daily vehicle losses for the Russian military in 46 months. In 2024, the Russians lost 16 vehicles a day, on average. In 2023, they lost 10. In 2022, they lost a staggering 26 a day owing to their failed mechanized offensive toward Kyiv and Ukraine's own successful counteroffensive in eastern Ukraine later that year.

Vehicle losses vs. ground gains

Unthinkable prior to Russia's wider war on Ukraine beginning in February 2022, the de-mechanization of the Russian armed forces is now complete. Large groups of armored vehicles make only infrequent appearances along the 1,100-km front line—and, when they do appear, usually get blasted to pieces by Ukrainian mines, drones, and artillery.

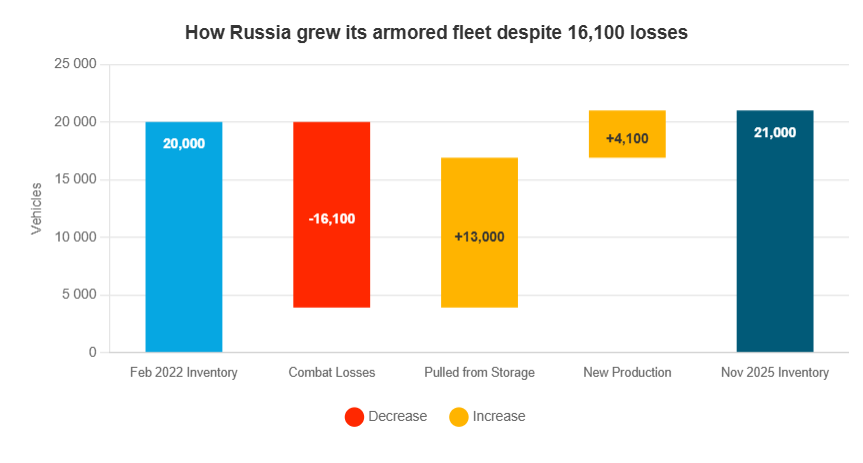

It's not that the Russians don't have more vehicles. To be sure, losses have been extreme. In total since February 2022, Russia has written off no fewer than 23,000 vehicles and other heavy equipment that the analysts at the Oryx collective have visually identified.

However, through a combination of new production and the reactivation of old vehicles from rapidly contracting Cold War stocks, Russia has made up for its equipment losses.

Yes, that means there's no huge stock of stored vehicles to replenish battlefield losses in some future war. For now, however, the Russians still have many thousands of tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, armored personnel carriers, and armored tractors.

They're just not using them very often or in large numbers. And for a good reason. Vehicles are easy targets for mines, drones, and artillery.

Trending Now

Infiltration tactics

Small groups of infantry marching on foot or riding on motorcycles or horses—yes, horses—are better able to slip past Ukrainian surveillance and infiltrate towns and cities where every building and basement is a potential shelter. Not all the infantry survive the march or the subsequent urban combat with manpower-starved Ukrainian brigades.

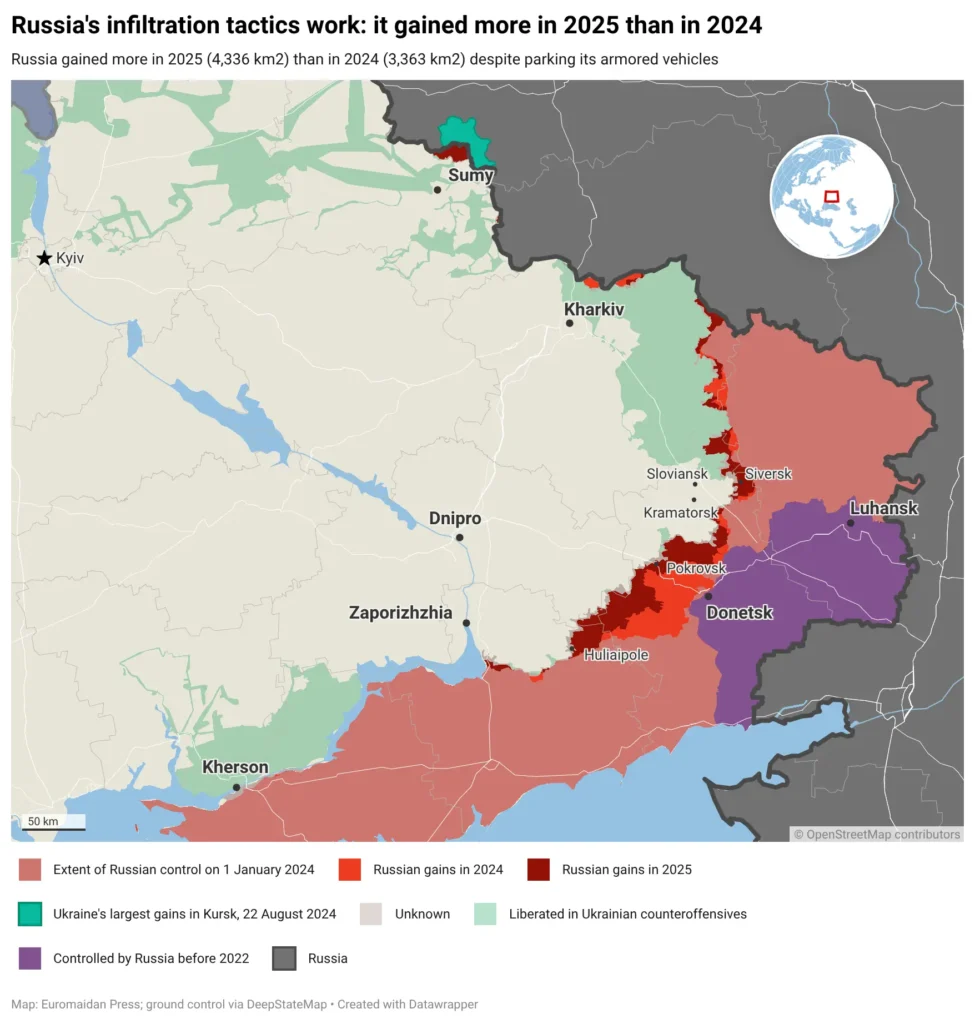

But enough do. And that's why, in the same year the Russians effectively parked their many thousands of surviving armored vehicles, they also gained 30% more ground: according to Euromaidan Press' calculations based on DeepStateMap data, 4,336 km2, including hundreds of square kilometers of Kursk Oblast in western Russia in 2025, versus 3,363 km2 in 2024.

What 2026 terrain means for Russia

Whether Russian infantry tactics work as well in 2026 as they did in 2025 depends on the Kremlin's mobilization system—can it continue to conscript or recruit more than 30,000 fresh troops a month?—and also on Ukraine's defensive strategy.

There's ample evidence that Ukrainian forces, short on infantry but stuffed with drones and artillery, fight better on the defense when they're defending open terrain between towns and cities. Just note the slowdown in Russian advances in Donetsk Oblast in recent weeks.

Having mostly or entirely captured Pokrovsk, Myrnohrad, and Siversk in Donetsk as well as Huliaipole in Zaporizhzhia Oblast, the Russians are now eying bigger prizes: Kramatorsk and Sloviansk in Donetsk and Zaporizhzhia city. But they'll have to march for tens of kilometers through open fields and scattered villages without significant cover from overhead firepower.

"It has become easier to defend fields or villages than large cities," French analyst Clément Molin wrote. "Fewer soldiers are needed, the Russian infantry is quickly spotted, and the increasingly numerous obstacles (ditches, barbed wire) sometimes prevent progress."

It should come as no surprise that Russian manpower losses increased as regiments shifted to infantry-first assaults in 2025. The assaults worked because last year's urban battlefields favored attacking infantry. Losses could increase even more in 2026 as the same infantry assault groups attack over unfavorable rural terrain.

It remains to be seen whether higher infantry losses will slow the pace of Russian advances this year.